January 15, 2014When Allan Greenberg was an architecture student in South Africa, he studied everything from Gothic design to European modernism, and had to draw important buildings from memory, with a T-square and a triangle. Photo by Lise Metzger; Top: A waterfront residence (1999) overlooking Long Island Sound, in Greenwich, Connecticut, reflects its owner’s love of the mid-19th-century Greek Revival houses of the American South. Photo by Wade Zimmerman. All photos courtesy of Rizzoli

In the peaceful world of Allan Greenberg, gambrel roofs slope toward wide green lawns, classical pediments perch over doorways and ionic columns frame stately facades.

In other words, many of the most enduring architectural elements and motifs known to man are on display in the buildings Greenberg designs. All is solidity and serenity, symmetry and sensitivity to scale — but the structures are not museums of style. With his deep understanding of old buildings and remarkable attention to detail, he enlists classical tropes to make more manageable the larger spaces we live in today and to disguise the technology that we require.

Greenberg’s friend and client, the author and tastemaker Carolyne Roehm, puts it this way in her introduction to the new book Allan Greenberg: Classical Architect (Rizzoli): “In the hands of a master such as himself, contemporary classicism isn’t just a pastiche or a rehash of historic precedents, but a flexible, beautiful style that lives and breathes.”

For Roehm, whose 1760s home, Weatherstone, in Sharon, Connecticut, was all but destroyed by an electrical fire in 1999, Greenberg added a structural steel frame inside the exterior stone wall for lateral stability, completely rebuilt the house’s interior and added an exterior porch. In the end, Roehm got her original house back, as well as a new two-story main room with a large winding staircase.

The facade of the new Humanities Building at Rice University (2000) expands upon the Byzantine-Romanesque architecture of the century-old surrounding buildings. Photo by Wade Zimmerman

A native of South Africa who has been based in the United States since the 1960s, Greenberg is erudition personified. (Among the many books he has written is the well-reviewed George Washington: Architect, which harkens back to a favorite era of the author’s.) But he’s unassuming, too: The very large classical homes for which he has become particularly known over his 40-year career are quite a bit grander than the man himself, who today leads a staff of 20 people from offices in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Greenwich, Connecticut.

Beyond residences, Greenberg has also done major university projects and retail designs, including the stately stonework for the Fifth Avenue façade of Bergdorf Goodman in New York. In discussing one of his signature projects, a Spanish- and Byzantine-inspired humanities building completed in 2000 at Houston’s Rice University, he gets to a paradox at the heart of his work: “People have had fights over whether this is a new or an old building. It looks like it has all the paraphernalia of the old buildings on the campus, but when you study it closely, you see everything is new.”

Greenberg’s trick was simple: Using the same brick, limestone and tile as the much older buildings facing the same courtyard, he dialed everything back a bit, incorporating fewer decorative elements and slightly flattening the façade. It doesn’t try to compete with its more established neighbors, even as it shows off lovely features of its own, like colorful glazed tilework.

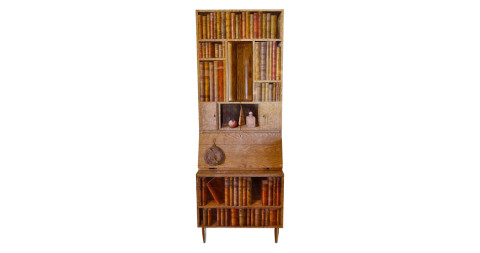

Demonstrating his diverse influences, Greenberg channeled both Shaker architecture and Mies van der Rohe’s work when creating this library addition (1995) to a Cambridge, Massachusetts, home. Photo by Richard Cheek

Greenberg credits his schooling in Johannesburg for his love of classical form. “I was incredibly lucky because the education in South Africa was unlike anything else in the world,” says Greenberg, who received an undergraduate degree in architecture. “It was the only place that taught classical and modern architecture.” He studied everything from Gothic design to European modernism, and had to draw important buildings from memory, with a T-square and a triangle.

Given the look of most of his work, Greenberg’s deep appreciation of modern architecture, and his tutelage by some of its foremost practitioners, comes as something of a surprise. Perhaps his greatest mentor was Le Corbusier, whom Greenberg met when in Paris on a year off from school. He asked for a job, a request he repeated over many months. “I drove this guy crazy,” Greenberg remembers with a laugh. “Finally he offered me a job, but he said I had to work for free for a year. Of course, I couldn’t do that.”

During the course of their discussions, Le Corbusier asked Greenberg for his opinion on the design of Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House, then in its early stages. “I told him, ‘I think it’s wonderful,’” Greenberg recalls. “So when I finished school, I decided, ‘If I’m not going to work for Corbusier, why not Utzon?’ And I did.”

For a year Greenberg lived in Copenhagen, where Utzon was based, working on the opera house. “It was the most interesting job I could possibly have gotten,” he says of the renowned building, with its striking, nested triangular sail shapes. “Utzon had a unique way of solving problems. I was really inspired by this man’s methodology.”

“I realized early on that people in America love and understand old American buildings.”

In 1983, Greenberg created a new Fifth Avenue entrance façade for luxury retailer Bergdorf Goodman, which had occupied its building since 1928. Photo by Peter Mauss/ESTO

After a few years of studying and working in Europe and then back in South Africa, Greenberg decided that an American graduate degree would help him pave the way forward. So he went to Yale and began his American life studying under yet another modernist: Paul Rudolph, then the dean of the Yale School of Architecture and known for stylish Brutalism. Today, Greenberg calls Rudolph “the greatest teacher of architecture I ever knew. Everybody who had been Paul Rudolph’s student — Bob Stern, Charles Gwathmey, Richard Rogers, Norman Foster — has this certain quality. There’s an unswerving commitment to what they’re doing.”

It was less his Yale experience that cemented his classical path than it was his 1960s American travels. The Mall in Washington D.C., Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and New York’s late, great Pennsylvania Station by McKim, Mead & White all had a profound effect on him as a young man. “I realized early on that people in America love and understand old American buildings,” he says.

As his friend the landscape architect Barbara Paca puts it, “Allan is filled with wonder when looking at architecture other than his own.” And that historian’s appreciative eye came in handy early on. By the 1970s he was ready to hang his own shingle, literally, and express himself in a traditional vernacular. Luckily, one of his first commissions was to create an addition to an 18th-century house in Connecticut.

A semicircular projecting entrance is just one distinguishing feature of this residence (2007) in northern California. Photo by Michael Biondo

“I picked up the language of that house as if I had been a friend of the architect at that time,” he says of his extension of the building’s classic, shingle-style roof over a one-story addition, expressing an empathic quality necessary to pull off this kind of time-bending project. “After that, I just decided I wanted to be a classical architect.”

Like anyone who roots for an underdog team — in this case, classical architecture is like the Met to modernism’s (usually) indomitable Yankees — it hasn’t always been easy for Greenberg amidst the doctrinaire modernists. Although he has taught at both Yale and Columbia, “They made it very difficult for me, in both places,” he says. “But I always had a lot of students on my side.” He adds that the increasing visibility in the last few decades of organizations like the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art has been a welcomed factor.

Those who commission him for houses tend to be not only wealthy, Greenberg says, but also “always very cultured, with a strong sense of what they want in terms of design.” And they are patient: The building process can take two and a half years, and he only works with certain builders. “We take a real pride in the construction of our houses,” he says.

Among the many things clients can appreciate about Greenberg — even before the first shovel of dirt is dug — are his finesse with smart siting and sensible arrangement of large volumes on solid axes. That is part of the reason a house he did in Silicon Valley, on the cover of the Rizzoli book, sold for a record $117 million. Not only is it neatly tucked below the crest of a hill, it manages to include a flying circular stair and a two-story domed garden room without seeming remotely like a McMansion.

Mariette Gomez of Gomez Associates designed the interiors of the Greenwich house, which incorporates Greek Revival–inspired plaster moldings and millwork. Photo by Wade Zimmerman

Greenberg’s attention to detail is evident all over the structures. “Allan will work with whomever in the office is involved with doing the drawings for a house,” says his New York associate Colette Arredondo. “He’ll even sit and draw the little moldings.”

Such famously hands-on Greenberg clients as Martha Stewart and Peter Brant require this of him. For Stewart, he composed what he calls a “village” of buildings at her Katonah, New York, spread, most of which were old structures that he rebuilt from the ground up, making subtle tweaks in windows and doors to modernize the passage of light and people. Then he constructed a brand new stone horse stable that looks like it’s been there for a century.

And his modernist apprenticeships sometimes manifest themselves in unlikely places: To a 2008 addition on an 1890 white clapboard house in Connecticut, for example, he added a Richard Meier–like volume of white-painted steel and glass that cleverly extends the lines of the original building.

But then he’s considerably less uniform in his tastes than one might think at first glance. “Le Corbusier never saw anything incompatible between the past and the present,” says Greenberg, who dreams of synthesizing his interests with a museum project one day, a home for art both old and new in a building with classical bones. “There’s just good architecture and bad architecture.”

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore