November 2014Bruce Davidson, shown here in a recent self-portrait, is best known for his black-and-white photography, but an ongoing exhibition of his work at New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery shows some of his most famous works in alternative color versions.

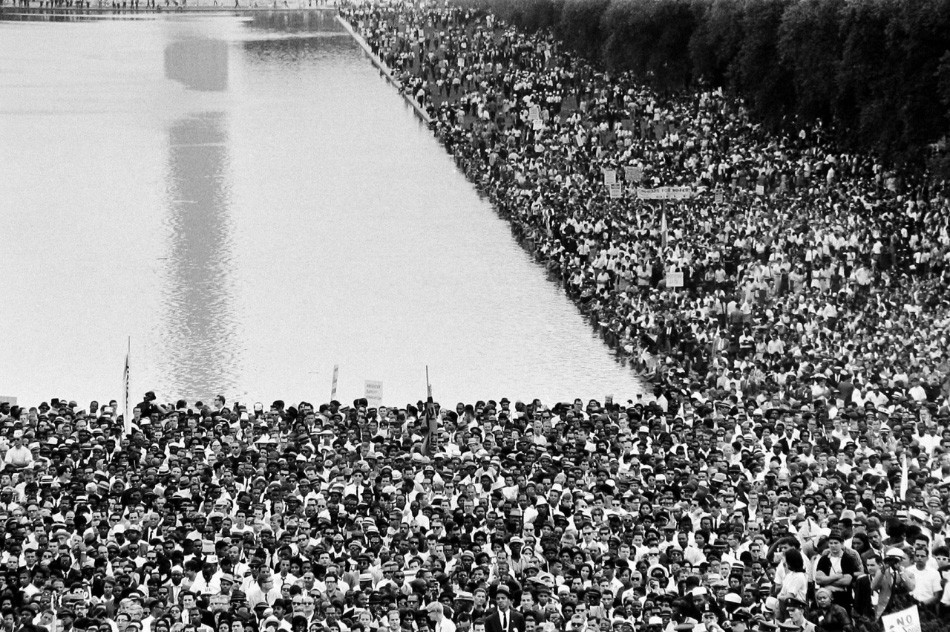

For more than five decades, the American photographer Bruce Davidson has been famed for “Time of Change: Picture of the Civil Rights Movement” (1961-1965), “East 100th Street” (1966-68) and other landmark documentary series that capture moments from struggling human life in intensely saturated gradations of black and white. “He uses them to eke out the extreme emotional ranges associated with light and shadow,” says Brian Wallis, chief curator of New York’s International Center of Photography. “Bruce always says, ‘Black and white are colors, too.’ ”

But all along, it turns out, Davidson has also been a master of polychromatism, a fact that can now be seen in the show “Bruce Davidson: In Color,” at New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery through December 6, and in a new monograph of the same title published by Steidl.

In the book, one discovers that Davidson, now 81, studied the process of making dye-transfer prints while in high school in Oak Park, Illinois, and later studied color with Josef Albers at Yale University. And from the show, one realizes that he often shot some of his best-known subjects in two very different ways: As a guest exclaimed at the opening, “That’s a really famous image, but it’s usually in black and white!” She was pointing to a 1965 shot of a bespectacled boy posing with a baby carriage before a sky filled with brownish smoke — one of several taken by Davidson while making his better-known monochromatic photographs of miners and their families in South Wales. (After realizing that color might better “articulate the grim reality” of their lives, Davidson writes in the book, he began carrying two cameras, one loaded with black-and-white film, the other with Ektachrome.)

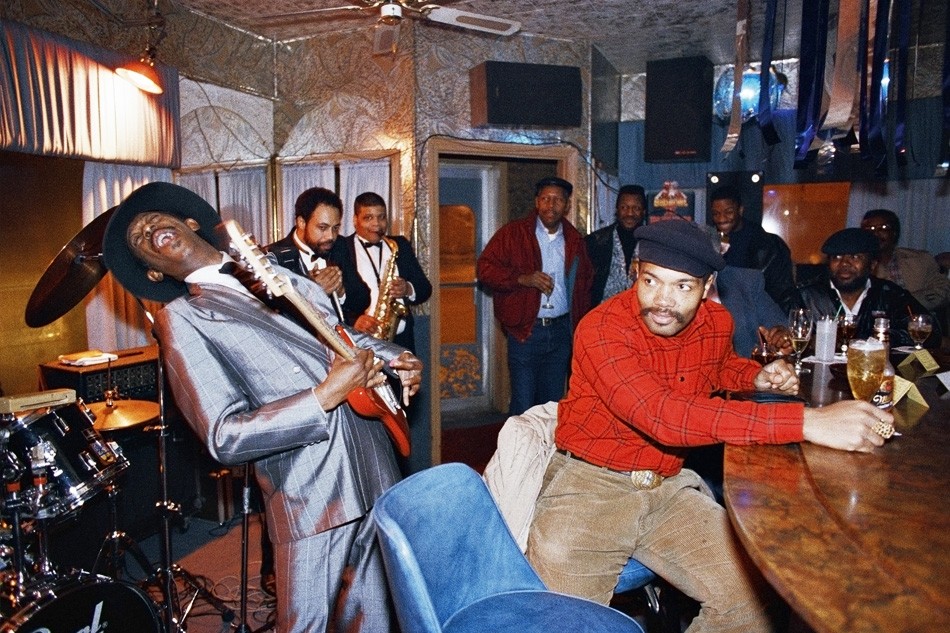

The show includes 35 such photographs made over 40 years. There’s a 1964 picture of a group of burka-clad women in Tehran, two wearing sexy white stilettos; and a 1989 photo of men listening to a band in a Chicago bar, shot in jazzy hues that suggest the music’s vigor. Also on view are examples from two of Davidson’s better-known color series, “Subway” (1980) and “Peace and Pastrami” (2004), for which he spent so many weeks at Katz’s Delicatessen, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, that customers assumed he was a waiter.

“Bruce always says, ‘Black and white are colors, too.’ ”

According to gallery director Nancy Lieberman, the idea for the book and the show arose while Davidson was going through his archives for Outside Inside, the massive three-volume catalog raisonné of his black-and-white work that Steidl published in 2010. “It was really around that time that he started to rediscover the color work,” Lieberman says, “There were many images he had never printed.” He became eager to bring them to light, she adds, while he was “still here to make it happen.”

The exhibition is also a family affair: In a room off the main gallery hang a number of arresting portraits by Davidson’s younger daughter, the Seattle-based photographer Anna Mia Davidson, 40, of people who live and work on sustainable farms throughout the Pacific Northwest. It’s her first New York gallery show, and next month these portraits and others will be published in her first monograph, Human Nature, from Minor Matters Books. (Another series, made between 1999 and 2009 in Cuba, where she traveled throughout the country capturing the positive aspects of life after the Revolution, will be published next year by Steidl.)

Anna Mia Davidson’s Olivia With Chicken, 2008, is on display in her exhibition, “Human Nature,” which runs alongside her father’s at Howard Greenberg Gallery, both through December 6.

Lieberman suggested the show in part because she recognized the elder Davidson’s style in “the way Anna sets up a picture, with the subject very central and very much engaged with the camera,” she says. “It’s clear from Anna’s pictures that she has a relationship with these people. And that was a very important part of Bruce’s early work” in projects like “Brooklyn Gang” (1959), for which Davidson, then 25, embedded himself with the Jokers, a Park Slope gang, and became one of the first photographers to infiltrate and document a rebellious American youth subculture.

In fact, much of the magic of Davidson père’s work lies in the way he seems to routinely be able to get his subjects to open up for his camera. Ask him how he establishes that intimacy, and he’s likely to crack jokes. “Did you ever see any pictures of me when I was twenty or twenty-five years old? I was absolutely gorgeous,” he says playfully with an air of easy bonhommie that speaks more loudly than his words.

Like the other works in her series “Human Nature,” Anna Mia Davidson’s John With Tractor At Dusk, 2008, featuring her husband, John Huschle , offers a glimpse of life on sustainable farms in the Pacific Northwest.

Yet his daughter, who clearly has the same ability to put her subjects at ease, is happy to discuss the family secret. While growing up, she says, she and her father had regular “photo days” together, when they’d each go out with a camera and work the the streets of New York as a team. Her older sister, Jenny, now a Seattle-based mixed-media artist who often uses photography in her work, had her own father-daughter photo days, too.

“We would walk the streets and find something interesting,” Anna says. “Dad would show me how to approach people and get their permission and then how to turn around and make myself invisible again.”

“The Protocol,” as it’s known in the Davidson family, consists of “being direct and up-front and explaining what interests you about that moment,” she says. “You say, ‘I like the way you look on that stoop. Would it be okay if I took your picture? Then you maybe do a little chitchat, warm them up and wait until the moment when they forget they’re in front of a camera.” And today, she adds, “It’s sort of second nature — you just begin having a connection that translates.”

“I don’t like the feeling of stealing someone’s soul,” Davidson finally explains.

“It’s just a treading-lightly-on-the-planet philosophy,” his daughter adds. “Photography is our voice.”