May 18, 2015The V&A’s current “What is Luxury?” exhibition shows a Fragile Future 3 Concrete Chandelier, 2011, by the New York outfit Studio Drift, above an installation of jellyfish models in jars, created by Steffen Dam out of glass, silver foil and carbon layers. Top: A 2009 headpiece made of gold thread by Giovanni Corvaja. Photos © V&A

What is Luxury?,” a new exhibition at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum on view through September 27, demonstrates that the answer to the question posed by the show’s title is a lot more complicated than a catalog of branded goods that sell for big bucks. While such items are included, this collaboration with England’s Crafts Council more often shines a light on objects — whether handcrafted or high-tech — created by individuals or small groups of artisans. Some pieces are beautiful, others amusing; some are thought-provoking, others mind-blowing. A few are all of the above. Historic objects make an appearance; among them a 19th-century Indian silver howdah (a fabulous perch on an elephant’s back from which one can watch the world go by) and a small but magnificent 18th-century bejeweled snuff box that may have belonged to Frederick the Great.

Overall, however, contemporary works dominate the show. Many of these are celebrations of imagination and invention; a few are critiques. In the latter category is “Rare Earthenware,” 2014-15, created by design studio Unknown Fields Division, working with ceramicist Kevin Callaghan. Following a trip to a “rare earth elements” mine in Inner Mongolia, the studio produced three vases in varying sizes, all made from black stoneware and radioactive mud removed from a lake contaminated by mining-related toxins. Each vase represents the amount of toxic material generated by the production of a smart phone, a laptop and a small car battery. (Displayed inside a sealed case and handled by staff with care, the pieces don’t pose a health threat.)

Artist-jeweler Giovanni Corvaja, inspired by the Greek myth of the Golden Fleece, spent over a decade perfecting a technique of creating gold thread. This Golden Fleece Headpiece, 2009, is made of around 100 miles’ worth of superfine gold threads. Photo © V&A

Quite a few of us, of course, consider such high-tech items necessities, not luxuries, but the inclusion of the vases in the show reminds us that the cost of our digital and automotive toys cannot just be measured in price.

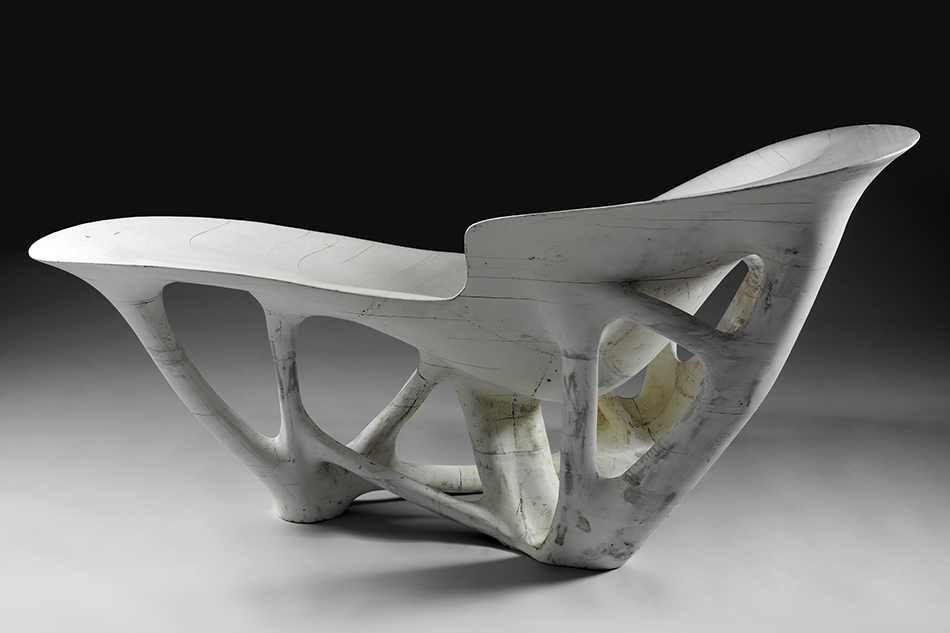

The exhibition also shows us how much seemingly disparate creators have in common. Dutch designer Joris Laarman, for instance, is represented by his Bone Chaise, 2006, a ceramic mold for part of an elegantly seductive furniture series in which forms are determined by a computer-generated algorithm based on the growth patterns of bones. Laarman explained to me that he and his team “invest a lot of time in experimenting to find new ways of designing things.” That’s a sentiment that could be wholeheartedly shared by Italian goldsmith Giovanni Corvaja, whose Golden Fleece Hat, 2009, also features in the show. It took Corvaja 10 years to discover how to produce gold wire thin enough to make into fur (a first). He then invented and fabricated the necessary tools to produce the hat entirely by hand, devoting, by his calculation, 2,400 hours to the process. Though Laarman relies on his computer and Corvaja creates works entirely by hand, they both have been served by the luxury of time, or what they call “the freedom,” to bring their visions to fruition.

In the days leading up to the show’s opening in late April, I met with the V&A’s Jana Scholze, curator of contemporary furniture, to learn more about the ideas behind it and the works selected that give these ideas life.

In one vignette at the V&A show, a Venetian chasuble (liturgical vestment), ca. 1670–95, decorated with an elaborate raised-needle floral lace, is shown beside a Vacheron Constantin wristwatch and an enlarged model of its movement. Photo © V&A

In 2007, the V&A in partnership with the Crafts Council staged “Out of the Ordinary.” That show was followed by “The Power of Making.” For this, the last in the projected series, you chose to focus on luxury. Why?

We wanted to question the concept, the category. If you ask people to name a luxury, most will answer by naming something expensive. But when my co-curator and V&A colleague, Leanne Wierzba, and I asked them to think a bit longer, their answers changed. Now they were not necessarily objects. They might be a concept like a holiday or a hobby or security, protection, health. Very often the answer we heard was time.

Were you surprised?

Yes. But then we thought, “Wow. Of course.” So, at the beginning of the exhibition we place a list of the responses, words like “Pleasure,” “Space,” “Rarity,” “Privacy.” From there, we move on to objects; they are our focus. To encourage people to look carefully at them, we organized the material into four main sections: “Creating Luxury,” “A Space for Time,” “A Future for Luxury” and “What is Your Luxury?”

The 2007 Vacheron Constantin watch is among the few “typically” luxurious objects in the show. Photo © Vacheron Constantin

You open the exhibition with a grouping that includes a bespoke Hermès Talaris saddle and a Vacheron Constantin wristwatch. Both are splendid pieces, but don’t challenge the idea that luxury equals branded, expensive goods for the very few.

We open up the subject by juxtaposing a variety of objects that we bring together to highlight various specific terms, among them “precision,” “exclusivity” and “passion.” For example, in the segment “Pleasure” we present the silver howdah alongside “Tea Cup Connoisseur Tasting,” 2013, by the design firm 1660 London. The trio of small, porcelain cups are of different sizes and shapes created to best enjoy various types of tea. (The tea-cup set, which is in the museum’s permanent collection, can also be bought in the V&A gift shop for a modest £55.00, or around $87.)

Tell us about FOMO, also in the show. It looks like a food truck in miniature.

FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) is a mobile publishing platform. The van goes to art fairs and biennials. Visitors can Tweet their zip codes to its computerized receiver and then, at 20-minute intervals, the computer picks one and Tweets its sender a message to come and collect a unique, computer-generated artist’s book. FOMO not only limits supply, and thereby creates scarcity, it demonstrates that luck and patience play their parts in what we consider luxury.