May 23, 2016In the mid-19th century, European royals and aristocrats jostled to be portrayed by Franz X. Winterhalter (shown here in an 1868 self-portrait), who is currently the focus of a survey show at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Courtesy Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe). Top: A detail of Princess Leonilla of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn, 1843. Photo courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Popular culture and the Internet teach us that today one can be famous just for being around fame. In subtler times, combining fashionable contacts with real talent guaranteed stature and wealth. Certainly, this applies to 19th-century German artist Franz X. Winterhalter. Between 1835 and his death, in 1873, the poor lad from the Black Forest became the most sought-after portraitist of the (mainly titular) royal courts remaining after the populist revolutions that rocked Europe starting in the late 1700s.

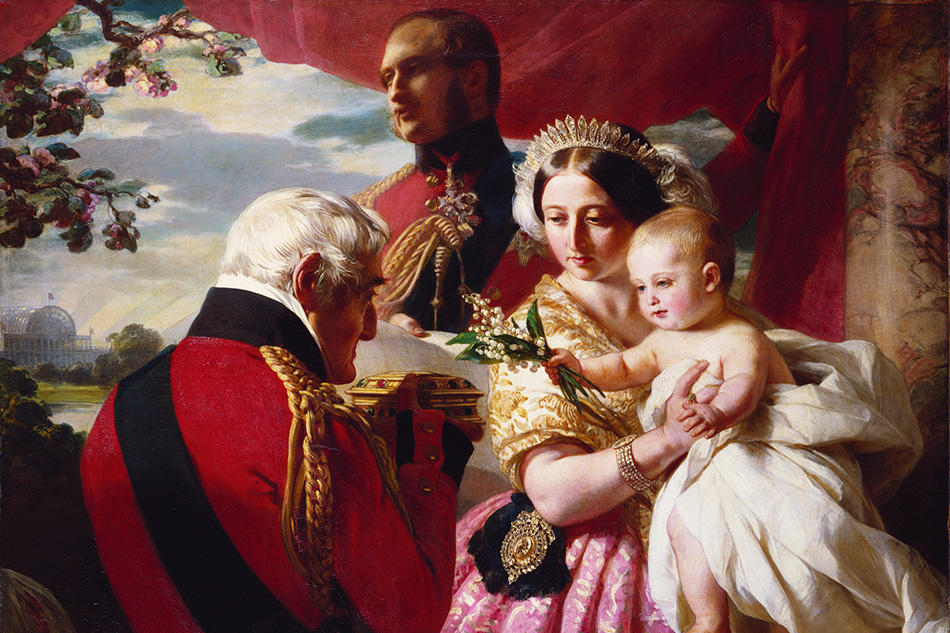

Winterhalter provides a window on that interesting moment between the passing of a feudal order and the birth of modernity — or what Gary Tinterow, director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, smartly calls “the nobility’s last hurrah.” In the survey show “High Society: The Portraits of Franz X. Winterhalter” (through August 14), the MFAH plays host to 45 stunning pieces by the painter, filled with such details as porcelain skin, lustrous pearls, translucent silks, bejeweled bodices and sparkly military garb.

Helga Aurisch, curator of European paintings at the MFAH, explains that for nearly 40 years in the mid to late 1800s, Winterhalter portrayed the richest and most powerful people in Europe, including such history-book figures as Emperor Napoléon III of France, Queen Isabella II of Spain and Emperor Maximilian, the Austrian ruler of Mexico. In 1842, the then-seasoned Winterhalter painted Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, who so trusted Winterhalter’s discretion and skill that, starting in 1842, they commissioned some 120 portraits from the seasoned painter, which remain in the palace collection today. One knockout depiction of a non-royal is the 1864 Madame Rimsky-Korsakov, a remarkably sensitive portrayal of the composer’s wife, which traveled to Houston from Paris’s Musée D’Orsay.

Madame Rimsky-Korsakov, 1864, is one of the portraits of non-royals in the show. The long-haired beauty was married to Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Photo courtesy Musée d’Orsay, Paris, on permanent loan from the Louvre

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Getty Museum and other world-class institutions also contributed major works. And Winterhalter’s stunning likenesses are paired with actual gowns designed by Charles Frederick Worth, the go-to couturier of the same fascinating crowd and era — a time when the press of modernity and the advent of photography made touch, tactility, color, texture and real-life panache all the more seductive.

On the eve of the opening of “High Society,” Introspective spoke with Aurisch about Winterhalter’s monastic teachers, rich benefactors who collected pictures of beautiful women and assiduous applications of abstract color.

You’ve scheduled a lecture to accompany this exhibition titled “Why Winterhalter Now?” So, why this show now?

Winterhalter has been a predilection of mine from my student days in Freiburg, Germany, very near the small village where he was from. I saw his work then and thought he was a seriously under-researched, under-displayed German master whose portraiture is both technically stunning and historically revealing.

Fast-forward to the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston several decades later.

Yes. You could say this project was thirty years in the making. The MFAH was putting together the wonderful 2006 exhibition “Best in Show,” focusing on spectacular paintings including dogs.

A favored accoutrement of nobility!

There was an excellent Winterhalter portrait that we wanted to borrow for that show from the Musée du château de Compiègne, north of Paris, and that just rekindled my conviction. We’ve partnered with the Compiègne and the Städtische Museen Freiburg for this project. The show originated at the Städtische and goes to the Compiègne from Houston.

Édouard André, 1857, depicts the French banker, parliamentarian, art collector and soldier in military regalia. © Culturespaces–Musée Jacquemart-André

It is interesting that Winterhalter’s life and art intersected with such wealth, yet he was from very humble origins.

He was poor but had support systems right when he needed them. He was educated in a monastic school by a particularly learned monk. Then he apprenticed at thirteen in one of the foremost Freiburg publishers, where religious and other texts were illustrated and printed. Winterhalter became a master lithographer and developed into an astoundingly gifted, precise draftsman.

But didn’t he receive official academic training?

A Jewish industrialist recognized his gifts and funded his travel to Munich, where Grand Duke Leopold I eventually sponsored Winterhalter’s entry into the Academy of Art, Munich.

It is interesting that at the Munich academy, he elected not to study under the conservative and stodgy master Cornelius but rather to work with the fashionable portraitist Joseph Karl Stieler.

Stieler was a major influence and a seasoned artist already working for the grand duke, a sovereign who had a penchant for beautiful women. The duke commissioned Stieler to do what he called a Gallery of Beauty, basically portraits of the most beautiful women in the area, irrespective of social stratum. They just had to be gorgeous.

History changes — men of power not so much.

Indeed, but the good part is that Winterhalter learned from Stieler the ability to really see and capture skin tones, fabrics against skin, transparencies and the like.

Empress Eugénie (Eugénie de Montijo, Condesa de Teba) in 18th-Century Costume, 1854, features the empress in profile, accentuating her prettier side. Photo courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Yet there is something quite warm and human about Winterhalter’s images of high-society women. No matter how elegantly dressed his sitters are, Winterhalter’s pictures, though filled with finery, are never slick or superficial, nor are they so idealized and objectified that they seem fake.

Winterhalter makes sitters somehow real, alive and approachable. In her journal, Queen Victoria commented that she appreciated his respectful, intelligent demeanor, that he was never ingratiating in his actions or his art, never tried to use his patrons to advance his status. She also says that she appreciated that you did not have to sit absolutely still and yet the portrait would be excellent. That was the level of hand-eye coordination, memory and observational skills Winterhalter brought to bear.

He traveled to Italy and Paris, and these trips really consolidated his maturity and stature.

From the academy, he went to Karlsruhe, where he tutored the Grand Duchess Sophie in drawing and produced portraits of the Grand Duke Leopold I, who appointed him court painter. Leopold sponsored his trip to Rome in 1832, and there Winterhalter added an understanding of Mediterranean color and light to his mastery of line.

He also formed instrumental relationships with the French court. How?

After Rome, he traveled to France and became not only court painter to Louis Philippe but also a favorite of his successor, Emperor Napoléon III. He won the favor of Empress Eugénie, who was no beauty. Winterhalter never lied in his paintings, but he learned little tricks — part of the face in shadow, a full profile of the empress in the excellent example we have in the show — and these skills, shall we say, found the best in his sitters.

In works such as Pauline Sándor, Princess Metternich, 1860, Winterhalter was using areas of abstraction to depict fabric and tone long before the Impressionists came along.

Can you comment on the decision to include some authentic evening gowns designed in the mid-1800s by Winterhalter’s contemporary Charles Worth?

These two men were the undisputed style makers of their day. Attire by Worth and a portrait by Winterhalter were the absolute must-haves of the mid-19th century. We are not sure if they knew each other, but certainly there is a close harmony between their eye for beauty and the tastes the two men both recorded and, in fact, helped to create.

Though clearly important to art history, Winterhalter is not widely known outside academic circles and seems to have been rather quickly forgotten after his death.

He became a victim of history and his skill. Going from prestigious commission to commission, he was tough to get a sitting with, and he did not do much else. Some academic critics objected to what was seen as his concentrating on frivolous subjects, and the avant-gardists, who rejected everything traditional, certainly didn’t court him. Yet, a full decade before Manet was celebrated for using areas of abstract color and seeing the descriptive potential of shape, you find this same technique in Winterhalter’s sketchy yet expertly visual areas of fabric and drapery, light and dark.

He sounds like a sensitive sort. Do we know if Winterhalter took this criticism hard?

He took it straight to the bank! He was renowned in his day, died a millionaire, had a well-run studio organized by his trusted brother, traveled the world and met fascinating people. We get the sense he lived a very creatively fulfilled life.