May 25, 2015Despite a life filled with physical suffering, Kahlo was a vibrant woman known for her charm and spirit, as well as her passion for all the colors of the natural world (photo © Nickolas Muray/Photo Archives). Top: Anchoring the exhibition at the New York Botanical Garden is a recreation of the dynamic landscape she cultivated around Casa Azul, the Mexico City home she lived in for most of her life (photo by Ivo M. Vermeulen).

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, who contracted polio as a child and then suffered multiple fractured bones and a pierced abdomen in a bus accident when she was a teenager, is most often remembered for the pain and emotional torment revealed in her self-portraits. However, a new exhibition called “Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life,” on view at the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) through November 1, shows a far more joyful side of her life and work.

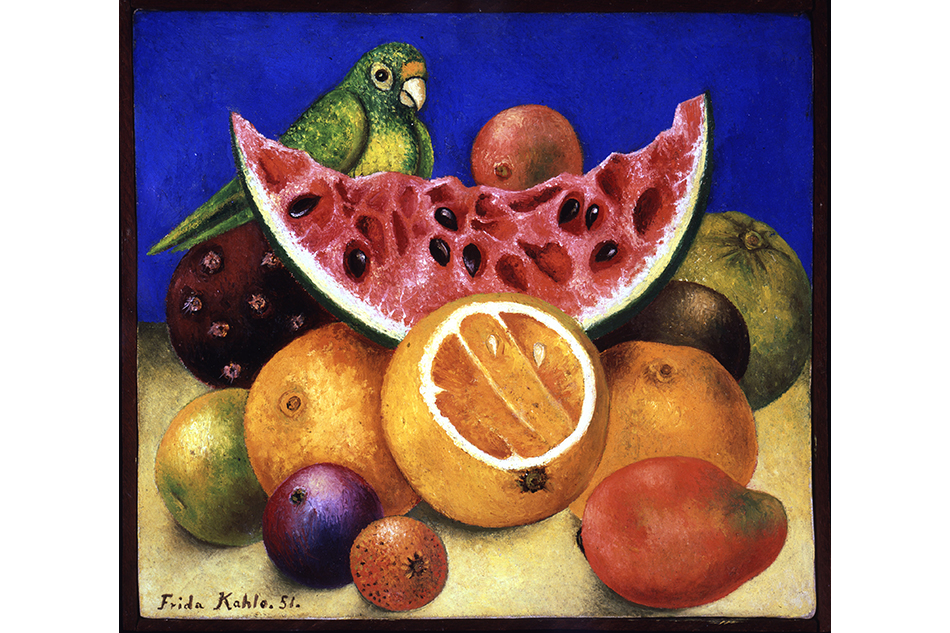

To view Kahlo through a horticultural lens is an ambitious undertaking — by all accounts this show is the first to do so — but NYBG succeeds brilliantly by taking a multilayered approach. This is done by displaying 14 original Kahlo paintings and drawings, all focused on her interest in flora and fauna and selected by Kahlo scholar Adriana Zavala, professor of Latin American art history at Tufts, and by a reimagining of the garden of her home, Casa Azul, in Mexico City’s Coyoacan district, where she lived for most of her life with her husband, famed muralist Diego Rivera. Casa Azul had been her childhood home, which she later turned into a highly original living and working space, painting every wall a vibrant color, filling the rooms with traditional Mexican folk art and religious ex-voto paintings, and creating an exuberantly colorful garden crowded with plants and trees. (Today Casa Azul is open to the public as the Frida Kahlo Museum.)

For this show, the elegant Enid A. Haupt Conservatory has been magically transformed into a lush garden of tropical and desert plants reminiscent of Kahlo’s creation. Snake plants, pomegranate trees, calla lilies, philodendrons, gardenias and sunflowers radiate brightly against a series of cobalt-blue walls, identical in color to those at Casa Azul (the name translates to “Blue House”). There are succulents, agave, fruit trees, piercingly colored dahlias and an Organ Pipe cactus fence. Every plant has been meticulously researched by members of NYBG’s curatorial staff, who consulted archival photographs, studied Kahlo’s paintings, perused her diaries and made trips to Casa Azul to determine their selections. They have spared no detail, even copying an existing pond whose tiled floor bears the image of a frog, and providing a re-creation of her desk, paints, brushes and easel. (The only things missing are Kahlo’s pet monkeys!)

Kahlo is often remembered for the pain revealed in her self-portraits — but “Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life” shows a far more joyful side of her life and work.

As in Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940 — perhaps the artist’s most widely reproduced work — Kahlo often juxtaposed motifs that conveyed her physical suffering with scenes of nature’s bounty. Photo © 2014 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

The paintings and drawings on exhibit at the NYBG’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library highlight the use of botanical imagery in Kahlo’s creations. Whether portrait or still-life, these works reveal the importance of nature to her art and emphasize her strong connection to the natural world — a connection that Hayden Herrera, Kahlo’s biographer, who accompanied me around the exhibit, believes was all the more intense because Kahlo had no children.

If proof were ever needed that NYBG is capable of crossing the line from garden to living museum, this show — a multifaceted celebration of Kahlo herself and of Mexican culture more broadly — provides it. Beyond the exhibition’s attention to Kahlo’s artwork, it also includes large-scale photographs of Kahlo, Rivera and their friends; an exhibit showing key sites around the Mexico City of Kahlo and Rivera’s world; a series of documentaries and shorts; weekly screenings of Julie Taymor’s 2002 film Frida, starring Salma Hayek; concerts featuring Mexican music; a specially commissioned art work by contemporary Mexican artist Humberto Spindola; a Mexican-inspired poetry walk; and even a Mexican food truck, called La Casa Azul Tacos.

Viewers come away from the show with a renewed sense that even the adversity the revered artist had to endure — she underwent more than 35 operations during her life — could not diminish her delight in the natural world. This life force, so strongly rooted in her house, garden and plants, was a central motif of Kahlo’s life, and of her art. Thanks to this show, we can better understand why, in spite of excruciating physical suffering and less than a week before she died, Kahlo chose to defiantly inscribe the words “Viva La Vida” (“Live life”) across the last painting she ever made — a watermelon, no less.