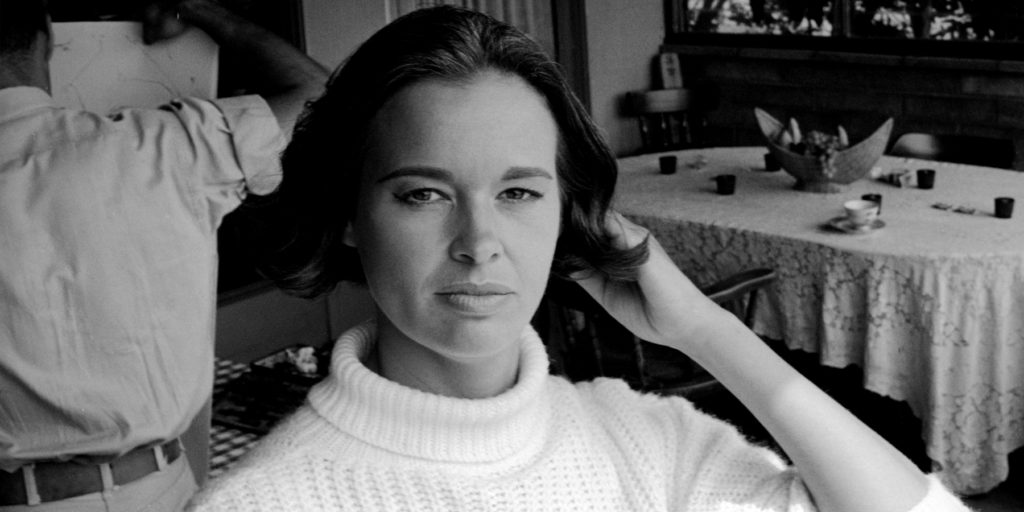

May 16, 2016At 92, the Manhattan socialite and style icon, seen her with her son CNN anchor Anderson Cooper, provides a view into her forever-captivating world via a new show of artworks at the 1stdibs Gallery in the New York Design Center (Photo by Jack Robinson/Vogue, courtesy of HBO). Top: Vanderbilt in a vintage photograph (Photo courtesy of HBO)

Writing in New York magazine in 2009, journalist Jada Yuan summed up Gloria Vanderbilt this way: “Certainly, as the heiress to a vast railroad fortune, Vanderbilt ran in the best New York circles. But she also went through four marriages — one to director Sidney Lumet — and affairs with Marlon Brando (‘fleeting but fun’), Gene Kelly (‘like Brando’), Howard Hughes (‘very private’), and Frank Sinatra (‘magical’). That she knows a thing or two about sex should come as a shock to no one.” And that, at the same time, she circulated in high, bohemian, artistic and literary circles in New York and Europe should also come as no surprise.

Right now, the 92-year-old icon and her singular life are experiencing a hard- and well-earned celebratory moment. There’s the new HBO documentary Nothing Left Unsaid: Gloria Vanderbilt & Anderson Cooper; the release of the epistolary memoir The Rainbow Comes and Goes: A Mother and Son on Life, Love, and Loss, conducted largely via e-mail between Cooper, the TV journalist, and his all-around celebrity mother; and an exhibition devoted to Vanderbilt’s artworks at the 1stdibs Gallery in the New York Design Center (through June 3).

Like a good memoir or diary, this show does more than present individual highlights in an artistic life—it documents a broader culture: the evolving tastes of Vanderbilt’s times and the artists and movements that influenced her and her cohort. This culture includes not only the art they liked and collected but also the clothes they wore, the attitudes they struck, the colors they favored and the way they furnished their homes.

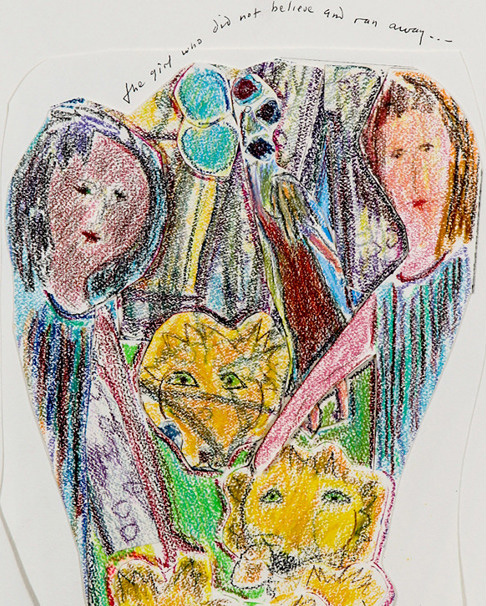

The works in the show are often based on dreams, leading to a kind of surrealism, but they also draw on theater, music, dance and literature. Vanderbilt seems to have created a world especially for her subjects — characters and narratives that she places in her own context. In a literal sense, she encapsulates her fascinations and fears in what she calls “Dream Boxes.” These are translucent containers, usually filled with dolls — some headless, some simply heads — like the one called Movie Star (2002), which has a glittery portrait bust inside. As Vanderbilt explained to Vanessa Lawrence in W in 2014, “I don’t use models at all, except I’m obsessed with [writer] Joyce Carol Oates’s looks. I’ve done dozens of paintings of her. . . . We’re great friends, but she’s never posed for me. I have a certain image in my mind that I keep trying to capture, but of course I never have. It’s really fascination with a muse.”

Vanderbilt depicts the private world of her imagination, privileging her impressions over pure representation. However, she is not a naif artist. She made art as a girl at boarding school, studied at the Art Students League of New York and spent time as a studio model.

All the visual arts serve her autobiographical needs. Like Vanderbilt herself, the paintings and assemblages on view are lively but cautious, visually talkative, mostly pretty and always spontaneous. They draw on art history in a distinctively personal way. From a sensitively rendered (and surprisingly competent) Marie Laurencin–like painting of a dancer that Vanderbilt created when she was 10 to darkly romantic Postimpressionist garden scenes to more contemporary canvases with thoughts scrawled on them, the paintings in the show are imbued with a kind of youthful enthusiasm, an attraction to beauty and an undercurrent of angst.

Anderson Hays Cooper, 1975 (at left), shows the newscaster as a boy, with his positive attributes scrawled around him. Vanderbilt captures the living room of her aunt Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney in 60 Washington Mews, 2012 (lower right).

There is a linear depiction of a young Truman Capote (Truman, 1956) standing coyly while holding two humble blossoms in his hand; a 1975 Pop-like portrait of a youthful Cooper that lists his virtues across the canvas (“tall,” “witty,” “brave”); and an expressionistic triptych (Faraway, 1983–2010), depicting a fairy-tale garden or forest retreat.

Among the most complex and compelling works is 60 Washington Mews (2012), a painting that captures the sensibility of the house where Vanderbilt’s aunt Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney lived and where Gloria spent much time during her youth. It’s like a written and visual diary entry, with the notation “I fell in love with this room and forever after tried to recapture it, but it was hard to define and it has always eluded me.” The composition is a bird’s-eye perspective of a cozy living room with pink walls, red carpet and a brown dog sprawled out. Two figures sit on separate sofas, and the vegetation outside seems to have pushed its way in. At the top right are two tombstones with a unicorn in front of them.

Vanderbilt has assembled the tragedies and triumphs of her life and career in this object- and memory-filled show. She translates her storied history into a resilient and optimistic visual autobiography, a perfect complement to the documentary and book, revealing not only what she has lost over the years but also what she has found.