November 16, 2015A former violinist, the renowned architectural photographer Hélène Binet compares architects to composers: “They made the music, and I play.” (Photo © Grazia Cantoni) Top: Binet’s 2013 Atacama Desert, Chile, 03. All photos © Hélène Binet, courtesy of ammann//gallery, Cologne

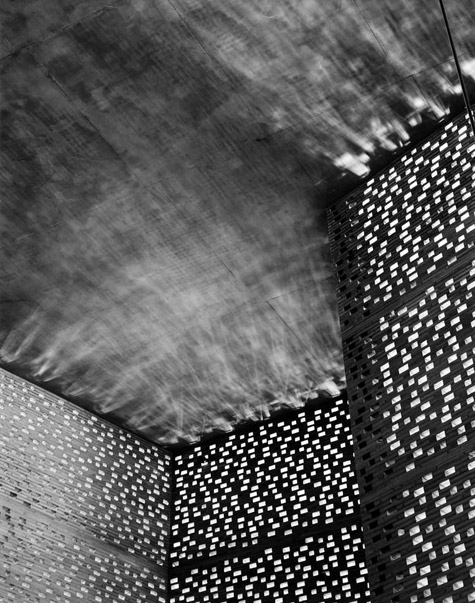

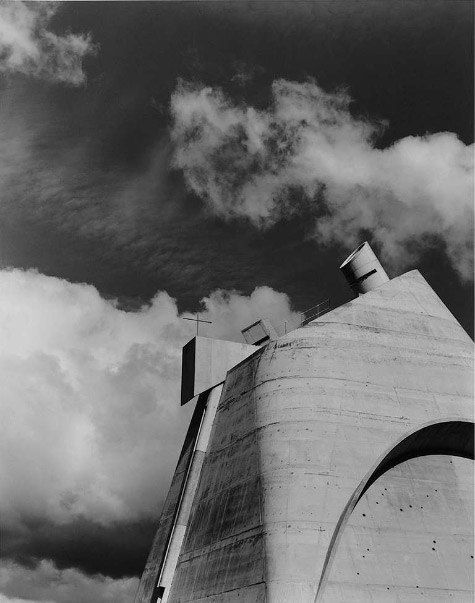

During more than a quarter century spent photographing architecture, Hélène Binet has developed a knack for capturing the poetry of structures, depicting details so exquisite that they appear to be abstractions: the subtle gap in the threshold of a Peter Zumthor museum in Cologne, Germany; the seemingly endless, somber progression of concrete tomblike slabs in Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin; the mystical play of light and shadow in Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin. The Swiss-born, Rome-raised, London-based Binet is, arguably, the preeminent living architectural photographer.

More recently, she has taken her exploration of space outdoors, beyond the manmade, for a no-less-arresting series of black-and-white photographs. Her landscapes, along with some architectural images, are on view in a solo exhibition at Ammann Gallery, in Cologne, through January 29. (Gabrielle Ammann has brought several images to her booth at The Salon Art+Design fair, at New York’s Park Avenue Armory, through November 16.)

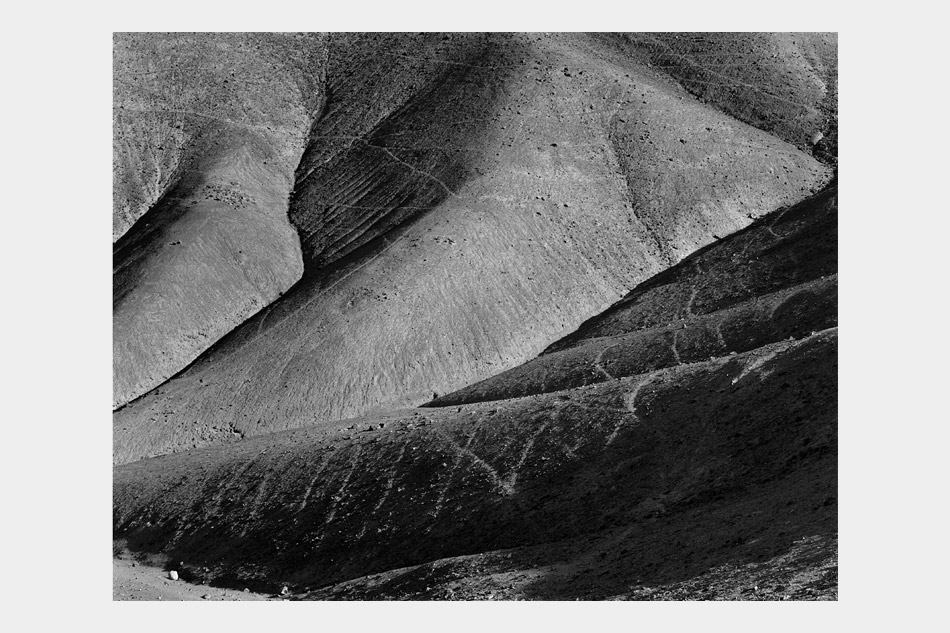

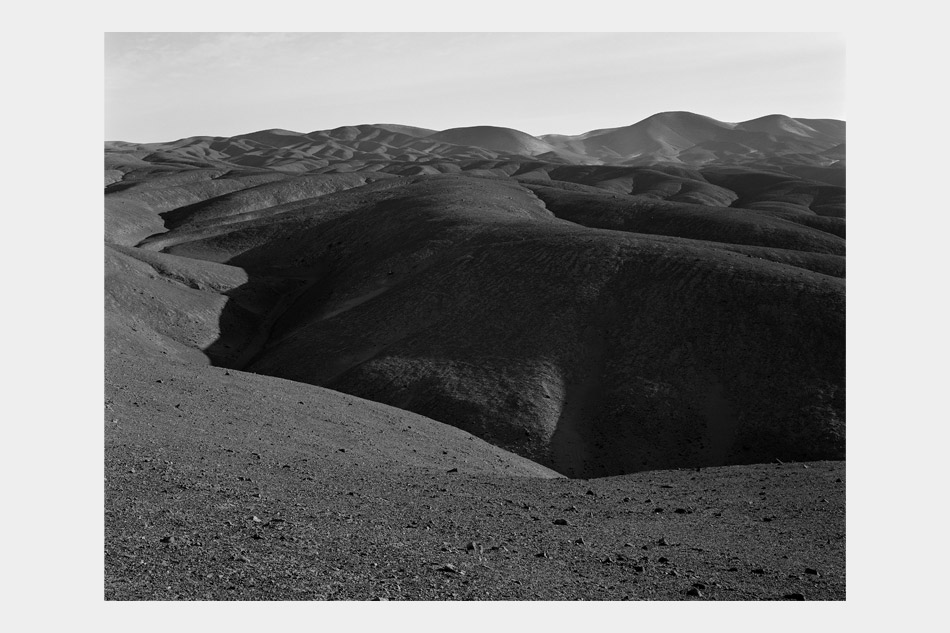

The stars of the show are Binet’s 2013 photographs of Chile’s Atacama Desert, a 600-mile-long strip bordered by the Pacific Ocean and the Andes Mountains that is said to be the driest non-polar region on earth. “In some places there are no traces of water ever recorded there,” Binet says via Skype. “Because there is no rain, you don’t have changes over the years. If you walk, your step will stay there for, I don’t know, fifty years. It has a very strange relationship with traces. It’s different from any other landscape.”

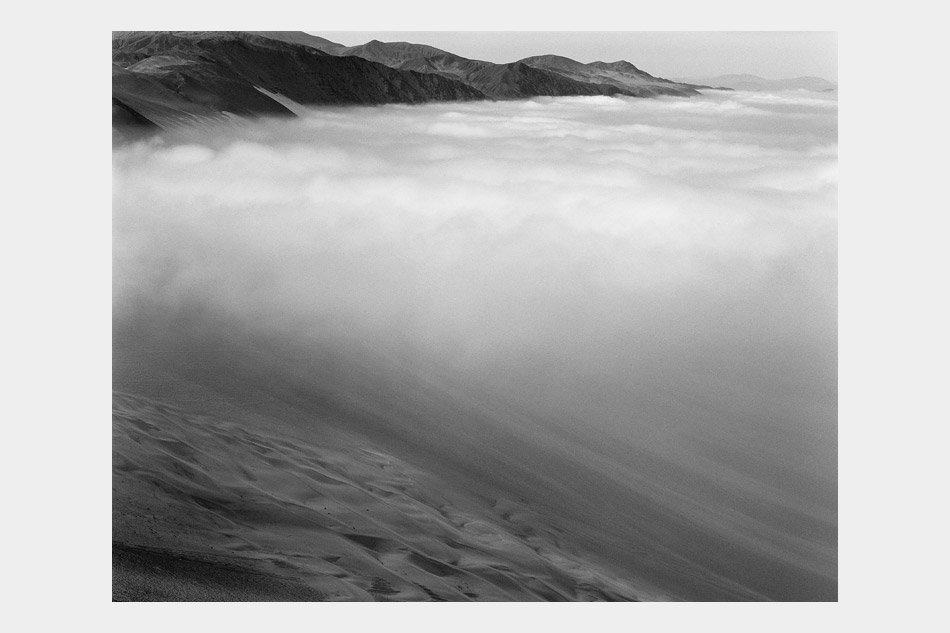

There are images of craggy mounds and deep crevices, but Binet was particularly intrigued with a peculiar fog formation that rises from the bay and climbs up a 2,300-foot slope. “Twice a year, when the temperature is not too hot and not too cold, you have a fog that comes,” she says. “This fog goes over the ridge, you are completely surrounded by it, and then it disappears into the deep desert. But you are wet. You are completely wet.”

One picture captures the mysterious fog cloud engulfing most of the mountainous coast, revealing just the peaks and, in the foreground, the miniature hills and valleys of a sandy slope. Another photo is almost entirely fog, save for the rocky ground.

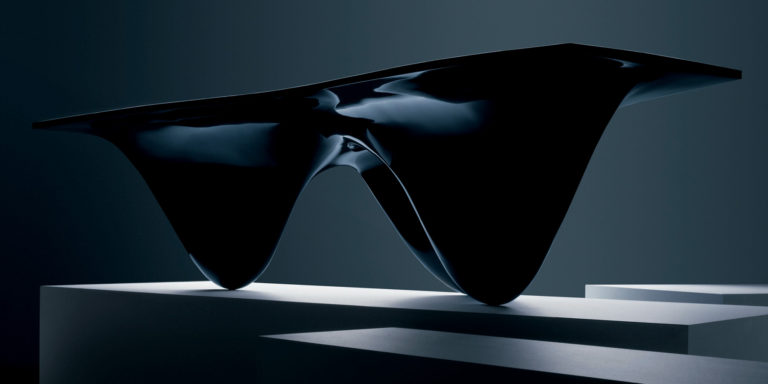

Binet’s Architectural Landscape in Baku portrays Zaha Hadid’s Heydar Aliyev Center, which includes a museum, a multipurpose hall and an auditorium in Baku, Azerbaijan. Photo courtesy of ammann//gallery, Cologne

Binet notes that while many contemporary artists have depicted violence against nature, she took a more hopeful approach. “There’s a group of people who have been trying to catch this water. They build what they call fog catchers, which are big textiles about the size of huge bedsheets that are hanging over the slope, and there is some structure underneath,” she says. “You can collect the water, up to five hundred liters a day. It’s so simple, it’s not expensive, and it’s so beautiful. I wanted to celebrate things we can use in an intelligent way. With no energy, we can make water. This fog catcher can produce water, and it’s very beautiful.”

Binet’s nature photos are far from a rebuke to her architectural images; rather, they are a progression. Her approach is fundamentally the same, relying on an acute eye for detail or, as she describes it, “seeing how a small part of something can reflect the complexity of something much bigger, not saying too much because what we don’t know and we imagine is very powerful. The image, like in architecture, is never about, say, the mountains with the huge view but is more about very intricate details.”

Years spent looking at spaces, she says, have trained her eye to see landscape more sharply. In composing her shots, she is disciplined about reducing. “We can hear better in the darkness,” she says. “If I give you less information, I can somehow touch you deeper.” The goal, she says, is to transport the viewer “to a mental space that is maybe the one we have when we read a book or when we dream.” She wants the viewer not simply to recognize a famous building but to know “how it feels to be there.”

Rather than “reproducing” a structure, she is intent on “capturing its soul. I would say they’re stories more than portraits. They’re little moments. They’re things that happen inside a space. They can be a light, a construction moment, a cracking of a wall, some traces of something.”

Part of what gives Binet’s images their rich depth is that she still shoots film on an analog camera. Her reasons — an analog camera is heavy, film is expensive, you can’t alter the photograph much after the fact — would seem to support a change to digital, but, rather, they keep her true to film. “I’m interested in limitation, not only in possibility,” and analog requires the “best of yourself,” she explains. “It’s like a performance: You are completely connected, and you have to produce something very good.”

Digital photography also tends to make images blander, “a bit the same, and sleek,” she says. “I like roughness, also. I like if something is real. I photographed something once, and somebody from a magazine Photoshopped it. I was in a little town, and there was a little bit of garbage on the floor, and this is part of the story of there, and you’re not going to take this away. This is real.”

Binet shoots a maximum of 20 images a day, leaving little room for error. “The light’s very important,” she notes. “I always say light is like dressing somebody: You can put on a beautiful coat or a very simple dress; the light really changes a place.” She does her own black-and-white printing; she enjoys working with her hands. “I like making objects, and they are objects, the prints that I do.” (She uses an outside lab for her occasional color photography).

Binet says she was less influenced by the majestic Swiss mountains of her birth than by the impressive structures of her childhood in Rome. “It was the Sixties,” she recalls. “I was living in the city center, running around like a little girl in all these beautiful places. It must have had an impact in enjoying spaces and architecture.”

Binet enjoys working with her hands, doing her own black-and-white printing. Shown here in Ammann Gallery in an installation view are her photographs of the Atacama Desert, including images of the fog rolling in from the bay. In the foreground is Ron Arad’s stainless-steel Two legs and a table, 1994. Photo courtesy of ammann//gallery

She studied photography at the Instituto Europeo di Design in Rome and met her husband, noted architect and urban planner Raoul Bunschoten, through a shared passion — not aesthetics but music. “We met much earlier, when we were young and playing in an orchestra,” says Binet, who was a violinist. “It was music that brought us together.”

Music metaphors still come easily to Binet. Asked if architects or their creations are her muses, she replies, “[The architects] are composing, and I’m playing. There’s room for me to say something, but they made the structure. They made the music, and I play.”

Has she ever considered trading places and designing a building herself? Her answer is clear-cut: “No, no, no, no.”