Furniture

by Cara Greenberg

The story of modern furniture is a never-ending one, it seems, producing a steady stream of books. In this season’s offerings, the under-sung designer Mario Bellini is serenaded; a spotlight is trained on the collaboration between MoMA’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr Jr., and architect Philip Johnson; and catalogues published in conjunction with major museum retrospectives celebrate the work of designers as different as Wendell Castle and Piero Fornasetti. There’s also a compilation of 100 British chairs titled, well, 100 British Chairs. It’s a bumper crop for the design enthusiasts on your holiday gift list.

December 14, 2015_dropcap_

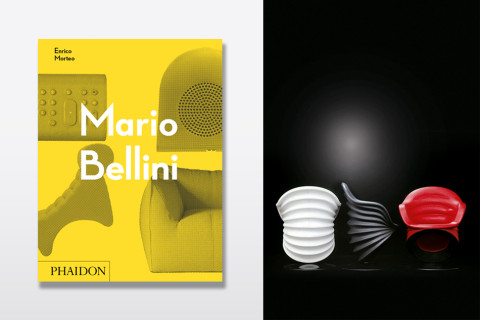

The first comprehensive monograph on the work of the renowned 80-year-old Milanese architect and designer, Mario Bellini: Furniture, Machines & Objects (Phaidon, $95) makes his multiple talents abundantly clear. It seems there isn’t anything Bellini hasn’t had a hand in, from TVs and the world’s earliest personal computers to cars and jewelry.

Right: Mario Bellini‘s prototype Teneride office chairs for Cassina, 1970. Photo © Bruno Falchi & Liderno Salvador

Bellini may be best known for his gorgeous typewriters and calculators for Olivetti and his editorship of the influential Italian design magazine Domus, but his frameless modular sofas for Cassina were icons of the 1970s, bringing leather sectionals into thousands of households, and his 1998–2000 chairs for Heller may be the most elegant plastic stacking chairs ever devised. This tome establishes Bellini as one of our era’s most essential furniture designers.

Bellini for Cassina CAB 412 chair, 1997. Photo © Aldo Ballo

_dropcap_

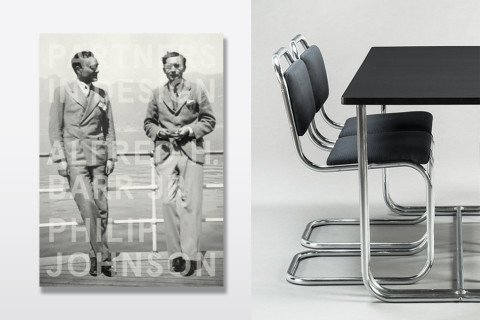

Without Alfred H. Barr Jr., the first director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and his lifelong friend, architect Philip Johnson (who was MoMA’s first curator of architecture), we might still be sitting in Empire chairs. Partners in Design: Alfred H. Barr Jr. and Philip Johnson (Monacelli Press, $50) reveals how the two men — the intellectual, reserved Barr and the voluble, sociable Johnson — brought the Bauhaus machine-for-living aesthetic into the American mainstream.

Right: Donald Deskey was just one of the designers championed by MoMA. His dining table and chairs, ca. 1930, made of chromium-plated tubular steel, plastic laminate and upholstery, are seen here. Photos courtesy of the Monacelli Press

Even the Depression and Johnson’s army service in World War II didn’t halt their decades-long series of exhibitions championing such seminal modern pieces as Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chair and Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel tables, along with works by American designers like Donald Deskey and Charles and Ray Eames. Chock-full of period interiors and installation photos, the book illuminates how by consistently bestowing the museum’s all-important imprimatur on new design ideas, Barr and Johnson established a modernist momentum that continues to this day.

Philip Johnson appreciated the artfulness of kitchenware and included it in the 1934 “Machine Art” exhibition he curated at MoMA.

_dropcap_

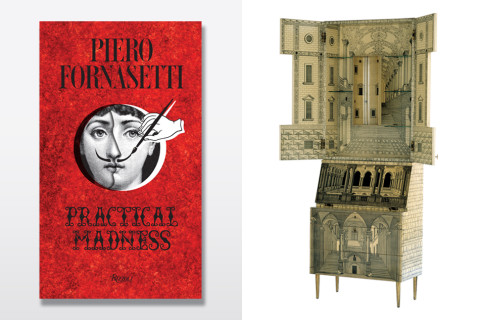

Piero Fornasetti, a singular talent if ever there was one, was the focus of a major retrospective at Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs earlier this year. The catalogue, Piero Fornasetti: Practical Madness (Rizzoli, $65), is a lavish survey of the multidisciplinary artist’s inventive output, including chairs disguised as stringed instruments, umbrella stands masquerading as packing crates, wardrobes whose interiors are pre-painted with clothes and boots, and other pieces of trompe l’oeil whimsy coveted by collectors worldwide.

Right: Piero Fornasetti‘s lithograph-on-wood Architettura cabinet, 1951. Photos courtesy of Rizzoli

Most dazzling of all are the tall 1950s secretary desks, produced in collaboration with architect Giò Ponti. Using a lithograph-on-wood printing technique plus hand painting, Fornasetti decorated one with delicate florals, gave another the green veins of malachite, made one resemble a book-lined library, another an Italian village with sides of stone. For anyone familiar only with Fornasetti’s ubiquitous Themes and Variations series of plates, decorated with seductive faces, this beautiful book will be a revelation.

Fornasetti printed, lacquered and painted his Music chair by hand in 1951.

_dropcap_

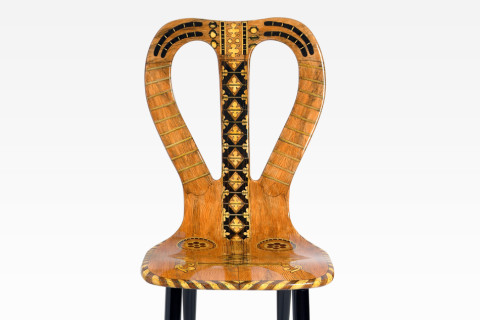

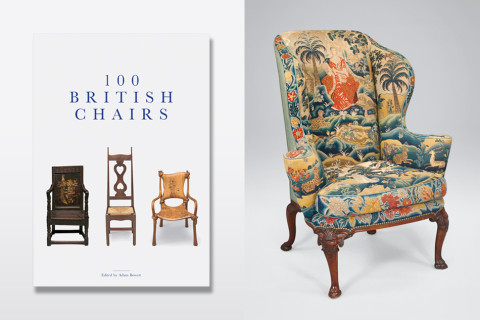

The compendium 100 British Chairs (Antique Collectors Club, $45) doesn’t claim to be comprehensive, but for the serious furniture aficionado, it is an indispensable reference. It pares down the huge category to museum-quality chairs spanning five centuries gleaned from two private collections, so there are gaps: Chippendale, rococo and mid-century modern seats are nowhere to be found. Instead we are treated to the strengths of each collection, from the throne-like carved-wood armchairs of the 16th and 17th centuries to the superlative craftsmanship and organic forms of John Makepeace, the leading light of contemporary British woodworking.

Right: Number 40 of the 100 British chairs is a walnut easy chair, 1730–40, with 18th-century needlework. Photos courtesy of Antique Collectors Club

In between, sumptuously photographed and each presented on its own page like a precious jewel, are early-18th-century chairs with vibrant Yorkshire-made needlework upholstery resembling Oriental carpets; winged easy chairs that actually look comfortable (one even reclines for sleeping), reflecting the increasing prosperity of 18th-century England; late-18th- and early-19th-century Windsor chairs in comb-back, hoop-back and Gothic variations; and primo examples from the Aesthetic and Arts and Crafts movements.

Numbers 16 and 17 are walnut and cane armchairs, 1710–15.

_dropcap_

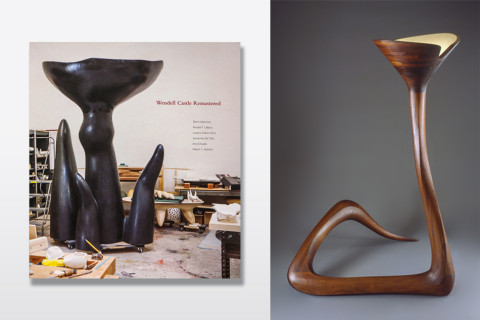

The work of Kansas-born Wendell Castle has always straddled the line between furniture and sculpture, from the voluptuous shapes in wood and molded plastic he produced in the 1960s to his more recent creations, which bring digital technologies into the mix. Castle’s wildly imaginative, era-spanning works are on display through February 28, 2016, at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design (MAD), and the 12-inch-square exhibition catalogue, Wendell Castle: Remastered (MAD and the Artist Book Foundation, $50), is a satisfying catalogue raisonée of Castle’s long career.

Right: Wendell Castle‘s mahogany Serpentine floor lamp, 1965–67. Photo courtesy of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

Alongside historically significant pieces, like the hybrid 1968 Table-Chair-Stool of African hardwood and the well-known plastic Castle chair of 1969 — the most conventionally sittable of his designs — is a bounty of recent works like High Hopes, a nine-foot-tall lamp resembling a towering mushroom in which Castle, still exploring materials and process, expands his vocabulary of forms with the help of 3-D scanning and modeling and a computer-aided milling machine called Mr. Chips.

Castle’s podlike Environment for Contemplation, 1969–70, consists of oak, gel-coated, fiberglass-reinforced plastic, flocking, foam and a flokati rug. Photo by Sherry Griffin/R & Company; © Wendell Castle, Inc. and courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum

Fashion

by Stephanie Murg

“Fashion must be the most intoxicating release from the banality of the world,” proclaimed Diana Vreeland. The same can be said of coffee-table books. And so the sartorial arts are increasingly the focus of lushly scaled, exquisitely produced page-turners. These four volumes each offer a distinct perspective on style, whether by spanning eras, covering the careers of extraordinary individuals or detailing a single splendid industry within an industry.

_dropcap_

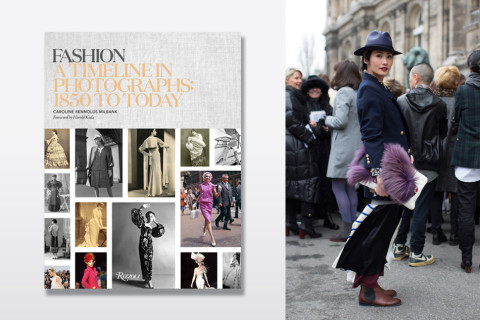

Long before selfies, there were cartes des visites. Made for analog sharing, the palm-sized photographic portraits both showcased trends and accelerated the pace of fashion changes. As such, these calling cards offer the ideal starting point for Fashion: A Timeline in Photographs: 1850 to Today (Rizzoli, $75) by fashion historian and Introspective contributor Caroline Rennolds Milbank.

Cover: Photos take you on a stylish journey of fashion throughout the ages. Right: A navy jacket, purple fox fur, riding boots and a charcoal fedora reflect the fashion of 2013. Photo by Scott Schuman, The Sartorialist

“Photographs show what fashion illustrations cannot: what people actually wore, what exaggeration they adopted and the actual prevalence of style,” Milbank writes. In tracing, year by year, sartorial shifts ranging from crinoline-supported skirts and Merry Widow hats to the Bohemian ease of Isabel Marant and the strategically effortless-looking ensembles of 21st-century “street style” stars, the book brings together multiple images on each page, inviting the reader to compare, contrast and contextualize.

This circa-1931 photograph shows a woman wearing a white crepe evening gown with a low-back décolleté, back sailor collar and floating arm panels. Photo courtesy of Timeline archive

_dropcap_

A coveted collector’s item among fashion aficionados, Grace Coddington’s first book returns to print after 13 years, complete with its original Michael Roberts cover illustration of the fiery-haired stylist whose narrative approach — in collaboration with the likes of Guy Bourdin, Helmut Newton, Bruce Weber and Steven Meisel — has yielded some of the most memorable fashion photographs of our time.

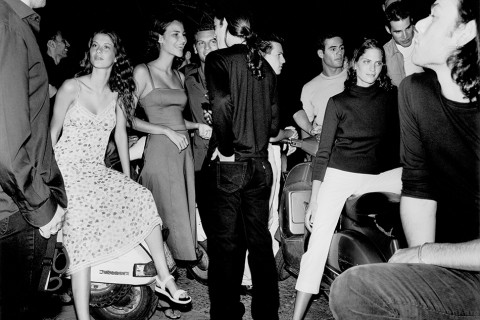

Cover: An illustration of Vogue creative director Grace Coddington by Michael Roberts. Right: This 1996 photo by Ellen von Unwerth shows Model Stella Tennant in France , with hair by Sam McKnight and makeup by Fulvia Farolfi. All reprinted from Grace: Thirty Years of Fashion at Vogue (Phaidon, 2015).

The re-issued Grace: Thirty Years of Fashion at Vogue (Phaidon, $150) is accompanied by a new handwritten, doodle-framed preface in which Coddington laments the changes wrought since its first publication — larger teams, digital images, the supplanting of models by “celebrities and people with the required number of followers on Instagram” — and reveals that she is at work on a companion volume that will span 2002 to the present.

Models, from left, Gisele Bündchen, Fernanda Tavares and Frankie Rayder in Italy in a 1998 photo by Mario Testino and styled by Coddington

_dropcap_

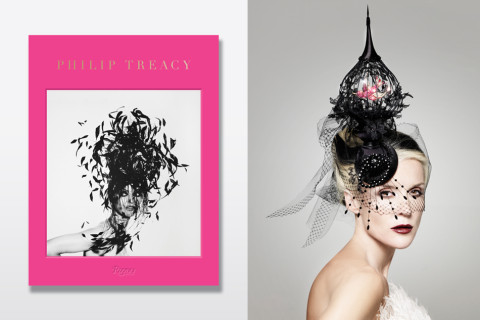

Irving Penn’s 1992 photograph of model Linda Evangelista peeking through a cloud of cockerel feathers is a Grace Coddington production that stars the work of Philip Treacy, the subject of a new monograph written with Marion Hume. Eschewing autobiography in favor of mapping “a joyful journey through hats,” the 15 chapters of Philip Treacy: Hat Designer (Rizzoli, $115) focus on subjects that include people (Alexander McQueen, Lillian Bassman), places (England, backstage) and things (masks, couture).

Cover: Linda Evangelista wears one of Treacy’s creations. Right: Daphne Guinness models one of the hat maker’s works of art in Vogue Gioiello, 2008. Photos courtesy of Philip Treacy

“The most interesting people in the world wear hats, and I get to meet them,” notes Treacy, who has crafted chapeaux for everyone from Marilyn Manson to the British royal family. In his studio, hand-carved hat blocks and exotic plumes mingle with Plexiglas and CAD drawings, and the book’s 250 photographs, annotated with Treacy’s musings and memories, are a testament to his belief that “a great hat exists outside its time.”

“A London Portfolio,” from the September 1999 issue of L’uomo Vogue, featured Treacy’s headwear in a Bruce Weber photo. Photo © Bruce Weber

_dropcap_

Today, the art of couture is synonymous with the haute ateliers and petites mains of Paris, but London was once home to an elite dressmaking industry of its own. These little-known houses and their immaculately made garments are revealed in the encyclopedic London Couture 1923–1975: British Luxury (V&A Publishing, $80), which combines rigorous scholarship with photography and illustrations by the likes of Horst P. Horst, Cecil Beaton and Norman Parkinson.

Cover: Victor Stiebel’s Window Box Bodice was photographed by Norman Parkinson for the March 1951 issue of British Vogue. Right: John Cavanagh tweed suit (with swan umbrella), from his Autumn 1952 collection. Photo by John French, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The first publication to take a detailed look at what editors Amy de la Haye and Edwina Ehrman describe as “a critical moment in the history of London fashion,” London Couture spotlights designers such as Norman Hartnell, Edward Molyneux and John Cavanagh, and their role in bridging the 19th-century fashion system and the youth-fueled style of the 1960s that cemented London’s reputation as a capital of cool.

A Francis Marshall illustration of a backstage scene at a fashion show, 1944. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Jewelry

by Shannon Adducci

Jewels and watches may be the ultimate holiday gifts (compact, sparkly, sometimes jaw-dropping), but if a pair of ruby and diamond chandelier earrings or a minute repeater wristwatch is out of reach, a book about them might be the next best thing. The holidays bring stacks of luxe coffee-table books filled with lush photographs of a variety of decorative objects, from Cartier diamond-and-onyx-encrusted panthers, to minimalist cuffs and pendants by Jean Dinh Van, to the fantastical bejeweled sculptures of Wallace Chan and the complex and highly ornate timepieces now on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

_dropcap_

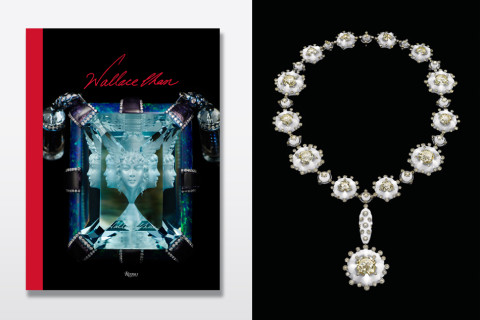

As prolific as Wallace Chan is, his name is heard less often than those of some of his compeers in the world of high jewelry design, such as JAR and Hemmerle. Perhaps it’s because the Hong Kong–based designer does not sell through retailers in the United States (except for a short foray in 2009 at Bergdorf Goodman), or because collectors of his pieces seldom part with them (only a handful have ever come up at the major auction houses). But among European royals and China’s wealthiest elites, Chan’s work is revered, and Wallace Chan: Dream Light Water (Rizzoli, $280) shows why.

Cover: Wallace Chan’s Now and Always necklace. Right: Plum Flowers in Snow necklace. All photos by Sirmon Tung and Fung Tsang

The book displays 85 of the designer’s creations in illuminating photographs on black backgrounds accompanied by minimal text by Juliet Weir de La Rochefoucauld. Most of the pieces are shot from different angles to highlight Chan’s jewel-layering and gem-carving techniques, including the so-called Wallace cut, exemplified by a stone inside which Chan has etched the face of Buddha so that it appears in a quindruple reflection. Chan is known for his flora and fauna motifs; his rock-crystal butterflies, jadeite dragonflies, rubellite beetles, ametrine fish and opal flowers are often paired with enormous fancy-colored diamonds. If there was ever any doubt, this book confirms Chan’s status as a jeweler of the utmost skill and dramatic vision.

Fluttery — Ragtime brooch

_dropcap_

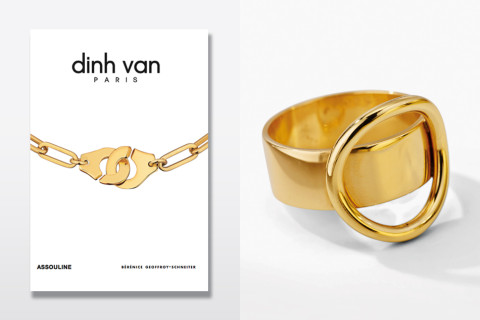

The minimalist gold and silver pieces in Dinh Van (Assouline, $25), by Bérénice Geoffroy Schneiter, are some of the best examples of how mid-century modernism expressed itself in jewelry. But the book, which showcases the work of French-Vietnamese designer Jean Dinh Van, feels more contemporary than vintage. Perhaps that’s because the designer, now 88, has maintained the same aesthetic throughout his half-century-long career, eclipsing contemporary designers who are now digging through the era’s archives for inspiration.

Cover: A 1977 Menottes Dinh Van R15 necklace in yellow gold, first model. Right: A 1968 Jean Dinh Van ring in yellow gold. Photos © Archives dinh van

Dinh Van worked at Cartier for 10 years before launching his own brand, leaving just as his peer Aldo Cipullo was starting to design at the French jewelry house’s New York headquarters. It’s impossible to ignore the two jewelers’ similarities, and it’s unfortunate that the book does not address how much influence (if any) they had on each other. One thing’s for sure: Dinh Van’s Menotte handcuff necklaces and rings and razor-blade pendants from today would sit nicely with Cipullo’s iconic Love bracelet.

Lame de Rasoir chain pendant in yellow gold, 1976

_dropcap_

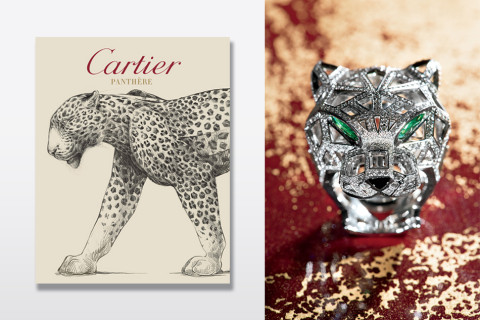

Is there any more powerful an animal in the jewelry kingdom than Cartier’s panther? Cartier Panthère (Assouline, $195) explores the history and cultural significance of the jewelry house’s favorite pet, from Daisy Fellowes’s sapphire-speckled brooch, to Maria Felix’s platinum, diamond and onyx two-headed panther bracelet, to the Duchess of Windsor’s famous pin of a feline resting on a cat’s-eye-sapphire sphere, which sold at her Christie’s Geneva sale in 1987 for $933,000.

Cover: A preparatory drawing for a Cartier panther jewel, 2014. © Cartier. Right: A panther-head ring in white gold set with 545 diamonds, two emeralds and onyx, 2014. Photo © Harald Gottschalk

In addition to myriad examples of Cartier’s diamond and onyx animals, the 300-page tome includes mid-century fashion photography of leopard-clad and bejeweled fashion models and stars like Elizabeth Taylor, who appears, wearing a spotted coat and matching hat, on a left-hand page opposite a photo of a cub wearing her Cartier ruby and diamond necklace. There are also essays by jewelry historians and experts Vivienne Becker, Bérénice Geoffroy-Schneiter and Joanna Hardy, as well as fashion editor André Leon Talley, who discuss the evolution of the Cartier panther, its significance in art and its relevance in the wider culture. Becker’s recollection of how Jeanne Toussaint went from Louis Cartier’s lover (affectionately nicknamed “Panther”) to the company’s creative director in 1933 is a grounding real-life complement to the fantastical Cartier imagery.

A panther watch-cuff bracelet in white gold set with 937 brilliant-cut diamonds, two emeralds and onyx. Photo by V. Wulveryck © Cartier

_dropcap_

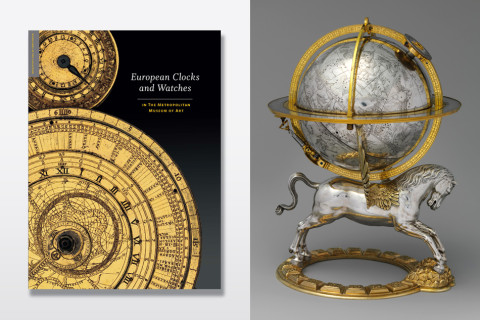

As the Apple Watch appears on more and more wrists, there is no better moment to contemplate earlier golden ages of timekeeping. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new exhibition “The Luxury of Time: European Clocks and Watches” (on view through March 27, 2016) does just that. It features elaborate clocks and watches from the 16th through 19th centuries, with German, French, English and Swiss provenances. Like the show, the accompanying catalogue, European Clocks & Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Yale University Press, $65), by Clare Vincent and Jan Hendrik Leopold, is nothing if not comprehensive. Standouts include a German automaton mechanical clock in the form of Diana and her chariot, circa 1610, and an English pair-case watch with a pink diamond, by Daniel Delander, 1715–19. The book delves into how watchmakers collaborated with goldsmiths, silversmiths, cabinetmakers, engravers and sculptors to create these elaborate, functional works.

Right: Gerhard Emmoser celestial globe with clockwork, 1579. Photos courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The last half-dozen years have witnessed a renewed interest in mechanical watchmaking in t, specifically from the big Swiss watchmakers, with early- and mid-20th-century wearables by Patek Philippe, Rolex, Vacheron Constantin and Breguet attracting million-dollar bids at auction. But exhibition and book focus not just on mechanics but also on the decorative arts that made these timepieces as beautiful (and complex) on the outside as they are on the inside.

Jean-André Lepaute mantel clock in gilt bronze, marble and enamel, ca. 1780–90. The figures were modeled by Augustin Pajou and cast by Étienne Martincourt.

Architecture

by Ted Loos

A sturdy building and a well-constructed book have a lot in common: They both require a solid overall concept and an agglomeration of individual elements that cohere, whether brick by brick or chapter by chapter. This season’s unusually strong bench of architectural books lets us in on the thinking behind some of the world’s best designs, from parks to boutiques to houses.

_dropcap_

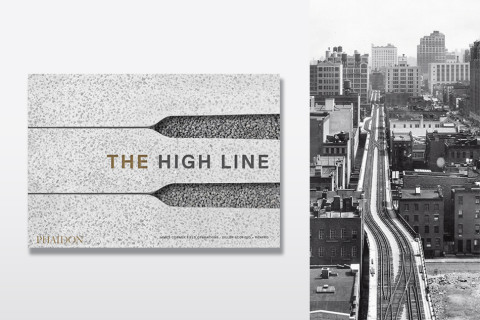

The High Line is only a skinny, one-and-a-half-mile-long park, but it is now perhaps the best-known urban public space of our age, celebrated for the way it transformed a disused elevated train track into a world-famous attraction, further gentrifying two Manhattan neighborhoods in the process. In The High Line (Phaidon, $75), the collaborators behind the project — the architects of Diller Scofidio + Renfro and the landscape designers of James Corner Field Operations — recount the history of the unlikely project, writing that their goal was to make the park “simple, wild, quiet and slow.”

Cover: The High Line’s signature pavers. Right: A vintage photo show the railway before its dramatic conversion. Photo courtesy of Kalmbach Publishing Company. Reprinted from The High Line (Phaidon, 2015)

This weighty and sharply designed tome is easily the year’s most significant urban-design book. Anyone who has been on the High Line will be amazed by the photographs of what it looked like before, not to mention the years of wrangling it took to get the park up and running — the book is quite journalistic in its documentation of everything about the project. And every copy comes with a discreet donation card that reminds readers that the High Line was created by private philanthropy and more giving would help it thrive in the future.

Today the High Line is as much playground as park and equal parts walkway and urban wonder. Photo by Iwan Baan. Reprinted from The High Line (Phaidon, 2015)

_dropcap_

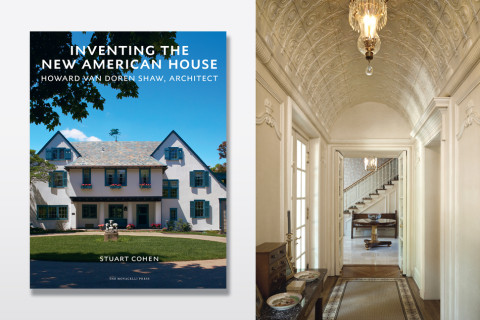

Around the same time and in the same region that Frank Lloyd Wright was experimenting with his Prairie School modernism, another architect was building more traditional homes — symmetrical, classical and solid. Howard Van Doren Shaw (1869–1926), just two years older than Wright, built a sterling reputation thanks to his work for the burghers of the Chicago suburbs. Now Inventing the New American House: Howard Van Doren Shaw, Architect (Monacelli, $65), written by modern-day Chicago architect Stuart Cohen, makes a case for the importance of a key designer of his age.

Cover: Howard Van Doren Shaw’s family home, built in Lake Forest, Illinois, in 1897. Photo © Dave Burk/Hedrich Blessing. Right: A view of the E. Norman Scott House, also in Lake Forest, through the home’s vaulted gallery to the stair hall beyond. Photo © Jon Miller/Hedrich Blessing, courtesy of The Monacelli Press

Using some Arts & Crafts touches but also pioneering a more open-plan layout that presaged how we live today, Shaw became a ubiquitous country-house architect; a signature trim color became known as “Shaw blue” in places like tony Lake Forest. The homes featured in the book may have antique-seeming elements — rooms specifically designated for trophies and guns — but they demonstrate that gracious and comfortable spaces never go out of style.

Shaw built the Edward Larned Ryerson Sr. house in Lake Forest in 1912. Photo courtesy of The Monacelli Press

_dropcap_

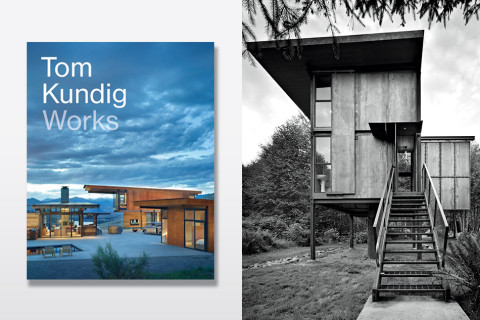

Seattle-based Tom Kundig has established himself as one of the most important residential architects of the Northwest, and indeed the whole country, with his rustic-luxe version of modernism. In Tom Kundig: Works (Princeton Architectural Press, $65), he authors a follow-up to his two previous best-selling monographs featuring 18 new projects. Industrial touches like rusting steel beams are made supremely elegant in his work; one of his signature elements is an old-fashioned handwheel, used to raise and lower everything from a bed to a whole wall.

Cover: Built for an adventuring family, Kundig’s Studhorse house, 2012, in Winthrop, Washington, gathers four buildings around a central courtyard and pool, like wagons circling a campground, requiring the homeowners to walk outside to get inside. Photo courtesy of Princeton Architectural Press. Right: Kundig likens the 350-square-foot Sol Duc Cabin, 2011, on Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula, to “a small perch for its occupants,” with an interior like a “warm, dry nest.” Photo by Benjamin Benschneider

Design writer, and Introspective contributor, Pilar Viladas notes in her introduction that Kundig is on record as needing both “the tough and the soft” in his designs. His ability to seamlessly blend them is on display here in homes located in a remote area of the Cascade Mountains as well as in the concrete valleys of Manhattan. Interspersed with vibrant images and a short text on each project are fascinating Q&A conversations between Kundig and the colleagues who helped him craft the residences.

The atmosphere of the loft-like, industrial-style three-story residential aerie, 2014, seems as far as possible from the stuffiness stereotypically associated with its location, on New York City’s Upper East Side. Photo by Jason Schmidt

_dropcap_

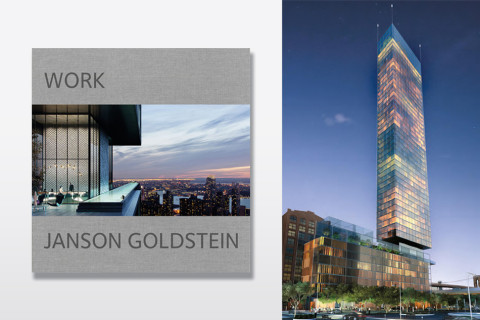

The 20-year-old architectural firm Janson Goldstein, based in New York, has been gaining attention of late for its hotel designs (including the one for the Andaz West Hollywood), its retail schemes (it was recently selected to design the Neiman Marcus flagship at New York’s Hudson Yards, due to open in 2018) and its residential work (not least of all, an apartment owned by two fashion industry stars in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood that was featured on the cover of Architectural Digest). Now comes the firm’s first monograph — Janson Goldstein: Work (Images Publishing Group, $80), edited and with an introduction by Introspective contributing editor Andrew Sessa.

Janson Goldstein’s schemes for a mixed-used hotel and residential tower in New York City’s South Street Seaport neighborhood exemplifies their signature luxe-mod architecture. The loft-like floor plans emphasize beautiful river and harbor views. Images courtesy Janson Goldstein Architects

Sessa writes that “the firm’s brand of modernism has a warmth and richness achieved by an often complex layering of materials and textures.” This is certainly in evidence in a lavish, seven-story Manhattan townhouse featured in the book, in which a base of muted colors and rich textures gives added pop to a collection of artworks by the likes of Andy Warhol.

Designed to evoke a classic prewar Manhattan apartment, a Chelsea residence in New York’s London Terrace complex combines antiques sourced from both 1stdibs and the Paris flea markets with millwork and a fireplace of Janson Goldstein’s own custom creation. Photos by Mikiko Kikuyama

Other Stories You Might Like

-

Beyond the Salon

Read MoreA second-generation contemporary-art gallerist and 1stibs dealer, Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn is the force behind Salon 94 (with three New York locations, including one in her own expansive Upper East Side town house). Now she's increasingly focusing her discerning eye on design.

-

The Coiner of ‘Mid-Century Modernism’ Recalls the Movement’s First Comeback

Read MoreBefore this era’s furniture gained recognition as timeless and iconic, it was considered just a trend that had fallen out of fashion.