June 29, 2015James Turrell, seen here in front of his famed land art piece Roden Crater, in Arizona, is the subject of the current exhibition “LightScape” at Houghton Hall in Norfolk, England (photo by Florian Holzherr, © James Turrell). Top: Houghton’s façade displays a light show specially created by the artist for the exhibition. Photo by Hugo Glendinning, courtesy of the artist and Houghton Hall

Ancient trees and acres of grassy parkland frame the long drive up to Houghton Hall, the 7th Marquess of Cholmondeley’s magnificent 18th-century home. A herd of rare white deer breaks into a slow-motion balletic trot at the sound of car wheels crunching the gravel drive. (Royal watchers note: This thousand-acre estate abuts Sandringham, the Norfolk retreat of Queen Elizabeth II, where her great-granddaughter Charlotte is being christened this month.) Enveloped by tall walls is a prize-winning garden planted with 150 varieties of roses, the work of Julian and Isabel Bannerman, the preferred husband-and-wife garden designers of the British aristocracy. Elsewhere in the park are contemporary outdoor sculptures — many site-specific, by such artists as Rachel Whiteread, Zhan Wang and Richard Long — that are a passion of Lord Cholmondeley (pronounced “Chumley”), a 54-year-old filmmaker. The star of his art holdings, however, has to be American Light and Space artist James Turrell, who can count Cholmondeley as his most enthusiastic British collector.

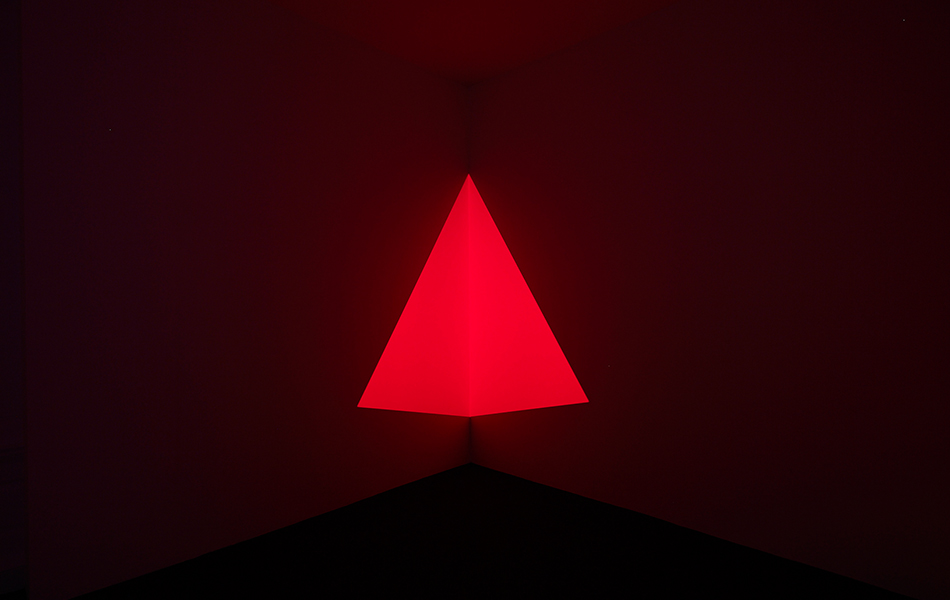

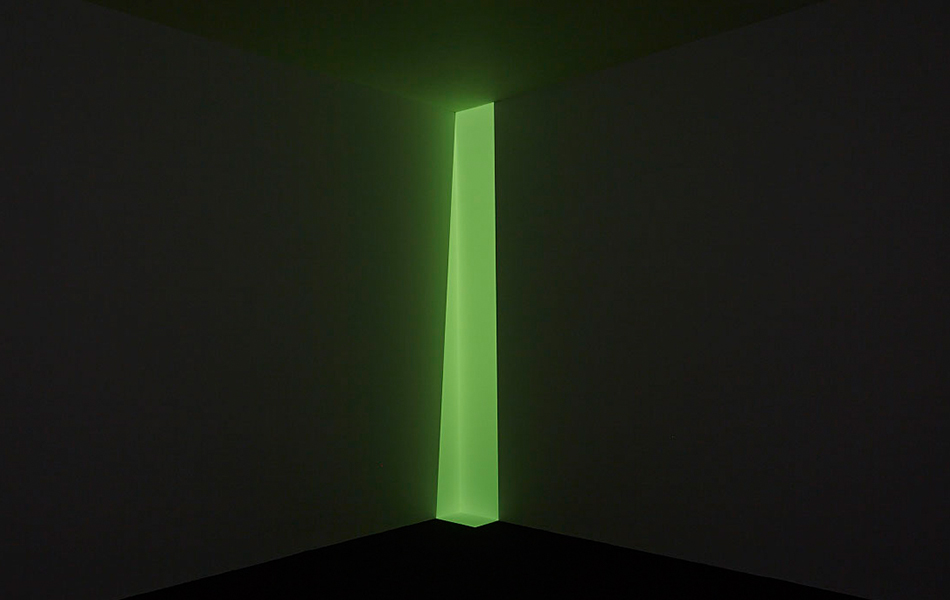

Houghton Hall is currently staging “LightScape,” an exciting, absorbing exhibition of Turrell pieces — six of Cholomondeley’s own as well as several loans — through October 24. Among these is a signature Skyspace (a purpose-built structure with an overhead aperture through which one can meditate on the constantly changing sky) and St. Elmo’s Breath, set inside an 18th-century folly in which shapes and colors become visible only after the viewer’s eyes adapt to the dark. The works are displayed on the grounds, in the stables and throughout the house. And on weekend evenings, Houghton Hall itself becomes a Turrell piece: As dusk turns to dark, a fantastical, slowly changing, 45-minute-long illumination transforms the majestic building’s main façade. Amethyst lights up the domes; lagoon-blue, the colonnades; the columns bleach to white, and then it all changes. The pediment becomes blue-gray, the urns above it violet and the colonnade shifts to electric green. Magenta makes an appearance, as do reds and oranges, all against a slowly darkening sky.

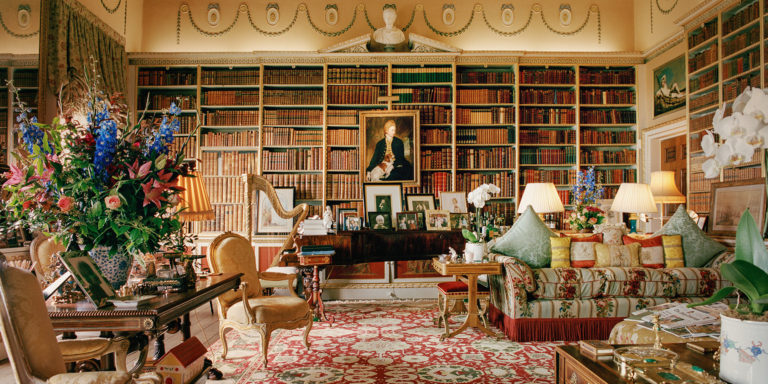

Mind you, even on a dreary, damp English afternoon, Houghton Hall is a mighty impressive place — inside as well as out. Robert Walpole, Britain’s first Prime Minister, who commissioned its construction in the 1720s, wanted a building that would advertise and enhance his power and position. It was meant to wow, and it still does. (Fortunately, Houghton Hall escaped the Victorian craze for “improvements” that stripped out original features from many grand houses and historic churches.)

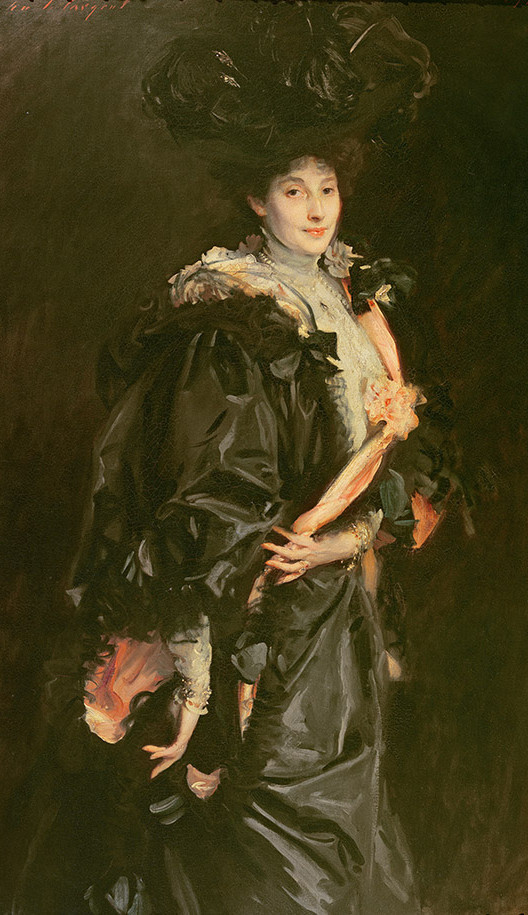

Colin Campbell and James Gibbs were Walpole’s architects. Their elegant yet austere exterior with its elongated triangular pediment and impressive double stairway up to the piano nobile was much influenced by Palladio. (It couldn’t have been more fashionable in that era of the Grand Tour, when rich Englishmen visited Italy and came home to emulate the architectural styles they’d discovered there.) The interior, designed by William Kent, was high fashion of a very different — extravagantly opulent — taste. Here, in State Rooms decorated to impress the grandest of guests, Kent designed deeply carved, richly gilded furniture and set it against a background of crimson walls and the Prime Minister’s famous collection of Old Master paintings. (Walpole’s grandson sold much of the art to Catherine the Great of Russia to pay off family debts.) The most exquisite of these knock-out rooms is the State Bedroom. Its precious silver-embroidered, green-velvet hangings and bed — with a curved headboard shaped like the clamshell out of which Venus rose from the sea — comprise a powerful advertisement not for political clout but sensuality.

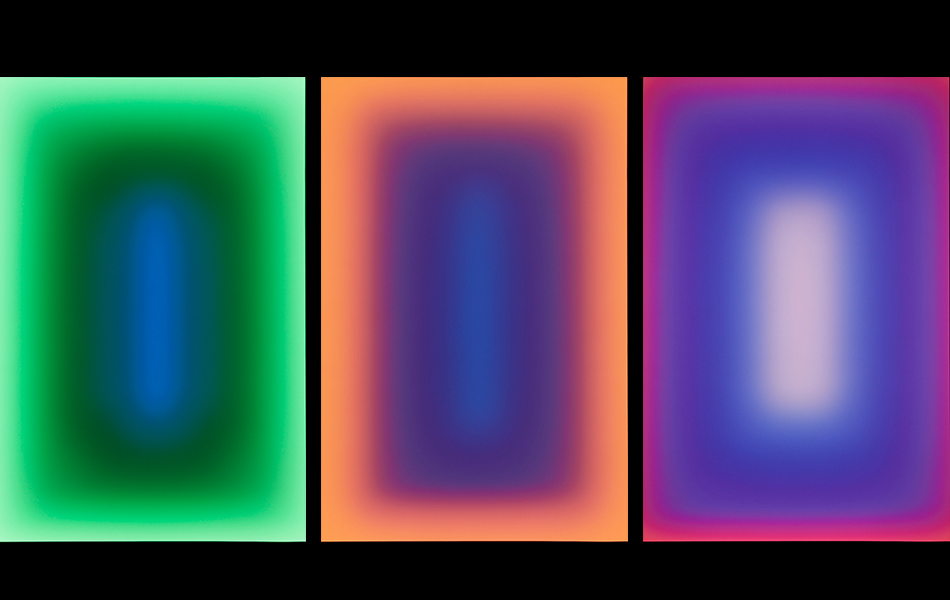

First Light, 1989-90, a series of 20 etchings in aquatint, is displayed in a dark corridor that sets off the ethereal glow of the works. Photo by Peter Huggins, © James Turrell

Understandably, many owners of stately homes stage attractions to boost visitor numbers (and income) in which exhibitions of contemporary art may feature. But “Lightscape” at Houghton Hall — which combines the work of a great artist, the inspired enthusiasm of a committed collector and a venerable grand house — stands apart from, and above, them all. Here, old and new sing in simple as well as complicated harmonies. It is an artistic triumph very much in the tradition established by Robert Walpole almost 300 years ago.

Houghton Hall is open to the public Wednesday, Thursday and Sunday. Uniquely for this year’s “LightScape” exhibition, which runs through October 24, it is open weekends, too, until an hour after dusk.