In gifted hands, lighting can be a crossover medium of the highest order, blending sculpture and illumination in equal measure. New technologies, like miniscule LEDs, are enabling adventurous designers and artists to realize forms and concepts that would have been all but impossible a decade ago. The result is a proliferation of luminous one-off and limited-edition objects that serve as a room’s centerpiece, even as they bathe a space in light. Here, five of the most promising talents in this burgeoning new field.

John Procario

July 27, 2015With their sinewy curves and elegant arcs, the lighting sculptures of Upstate New York—based designer John Procario evoke living forms and gestures that seem almost human. Photo by Stacey Lopez

John Procario trained as a fine artist, but when he’s making his wildly sinuous wooden lamps he also needs to rely upon the strength of an athlete. After steaming the wood for flexibility, “I literally wrestle each piece down into a position I like, without forms,” he says. “It’s quite a process.” Based in Cold Spring, New York, Procario began pushing his woodworking skills to the extreme while studying sculpture at SUNY Purchase College. “I was making sculpture based on the idea of wood as a metaphor for the human body,” he notes, pointing out that bones and muscles, like lumber, are flexible until they reach their breaking points. “I was creating dancer-like gestures by manipulating the form within the confines of the wood’s flexibility. It was a collaboration between me and the material.”

Three years ago, he translated that concept to LED-based pieces that he calls “free-form lighting sculptures,” which are sold by Worrell Smith Gallery, in Westport, Connecticut. Lamps appear to sprout from tabletops with as much malleability as fabric ribbons, splitting open to reveal lines of light, while pendants capture a sense of movement frozen in midair. A growing part of his business are large-scale commissions completed for such blue-chip clients as Dallas-based interior designer Emily Summers and an upcoming hotel in Dallas by Steven Song Design Lab. “These pieces use the same language,” says Procario. “But more space gives me more opportunity to play with the shapes.”

Charlotte Cornaton

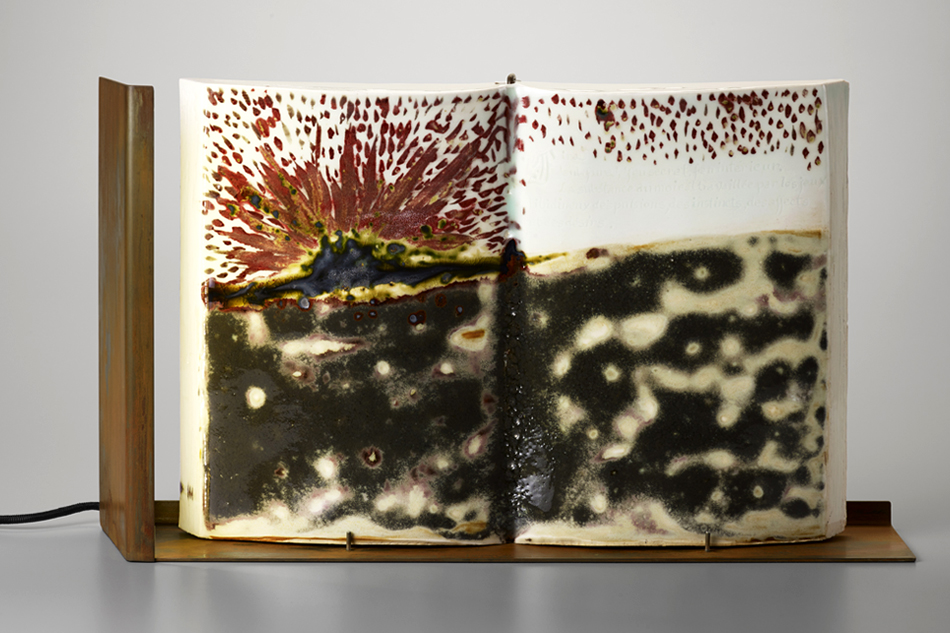

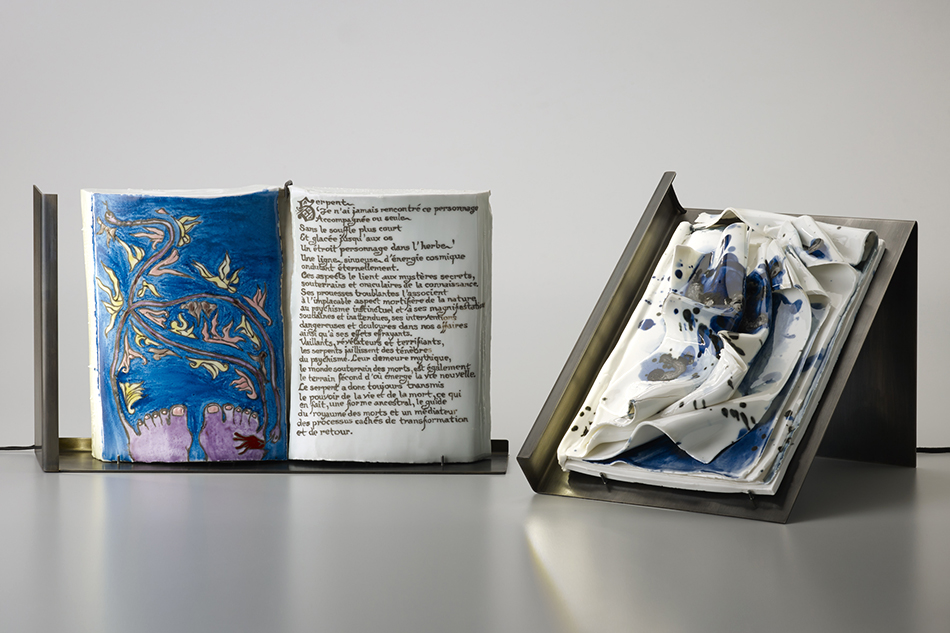

Paris designer Charlotte Cornaton plumbs the depth of human experience with her hauntingly beautiful book-shaped lights, all of which employ a range of complex ceramic techniques that include Chinese porcelain. Photo by Alain Cornu

Charlotte Cornaton’s home base is Paris, where she’s represented by Galerie BSL, but she considers the world her studio. “I’m always traveling to discover different techniques and traditions in order to mix them together,” says the artist, whose primary focus is ceramics. “It’s a nomadic way of working.” Her latest voyage took her to Jingdezhen, China, the historic center of porcelain production, for a two-month residency during which she developed a series of incredibly delicate — and illuminated — ceramic books. With rippling pages, the books present drawings and text inspired by Cornaton’s nightmares, interpreted via the writings of Carl Jung. “When it comes to symbolism, Jung was always comparing Occidental and Oriental cultures,” she says, which provided natural inspiration for a French designer working in Asia.

Cornaton employed three traditional Chinese porcelain techniques that she learned on location – engraving with celadon glaze, cobalt calligraphy and cloisonné enamel — to adorn the pages with French text and images including horses, volcanoes and serpents. Collectively named Insomnio, the finished pieces are presented on patinated steel stands lit by hidden LEDs, which give each piece a ghostly glow. “I’m a huge lover of books,” says Cornaton, “and I tried to capture their promise of knowledge and light in the design.”

Bec Brittain

Brooklyn-based designer Bec Brittain uses her expertise in metalworking to create stunning geometric lights that recall the micro and the macro — from the primordial to the cosmic. Photo by Jesse Dittmar

The faceted SHY Light, Bec Brittain’s now almost-iconic chandelier, uses thin LED tubes to carve three-dimensional volumes out of thin air. For the Brooklyn-based designer, shaping form and space comes naturally — she studied architecture at London’s Architectural Association before turning her attention to smaller scale, handcrafted products. Brittain’s initial passion for metalwork came from an early job at the upscale door-hardware company H. Theophile, in New York. From there, she added light to the mix while serving as design director at Lindsey Adelman‘s studio.

Since going out on her own in 2011, Brittain has become best known for suspended lamps with striking crystalline forms, which she sells through The Future Perfect. Her Maxhedron fixture has a gem-like shape created with pieces of one-way mirror that only reveal the interior when the light is turned on, while her Echo pendants alternate LED tubes and triangular pieces of colored glass or mirror to multiply and refract light. Her latest design is Zelda, a lighting system that uses LED tubes in flattened diamond shapes. “It allows me to create planar shapes as opposed to faceted volumes,” she says “I’m using them concentrically, like orbits, or like links in a chain.” These days, she splits her time between commercial production and pure experimentation. “Those are the two different sides of my brain,” she says, “and of the business.”

Thaddeus Wolfe

The molds that Thaddeus Wolfe creates for his geologic, craggy-glass light sculptures are destroyed in the casting process, thereby rendering every product absolutely original — and inimitable. Photo by Joe Kramm

It’s fitting that Thaddeus Wolfe grew up in Toledo, Ohio, which is known as the Glass City because of its history of glass innovation and industry (see: local architects Walter and Weeks’s 1936 Owens-Illinois research building made from glass bricks, or works from the city’s studio-glass movement of the 1960s). After initially enrolling in the painting program at the Cleveland Institute of Art, he says he “ended up taking an elective course in glass and getting really, really into it.” More than 15 years later, Wolfe, now based in Brooklyn, is among the most provocative American artists working in the medium, regularly experimenting with processes and techniques to give glass dramatic new forms, finishes and textures.

Each one of Wolfe’s creations, available through New York’s R & Company, is one-of-a-kind, by necessity. To produce his craggy glass pieces, which resemble stalagmites or chiseled blocks of coal, he creates the initial form in Styrofoam or wax, makes a plaster mold and blows in molten glass — a process that destroys the mold every time. He then works the resulting piece by hand, selectively grinding and polishing the rough outer layer to reveal lustrous colored glass inside. Adding light to the equation makes his creations that much more dramatic. “It shows the surface texture and detail,” says Wolfe. “When you see the same piece with the light on versus off, it’s completely different.” R & Company will host a solo exhibition of Wolfe’s latest work this September.

Niamh Barry

Dublin designer Niamh Berry, here pictured with her Counterpoise light, 2014, channels dynamic movement with her lights, which comprise interlocking, irregularly shaped hoops of bronze or steel and LED-backed opal-glass diffusers. Photo courtesy of Todd Merrill Studio

Dublin’s Niamh Barry started her career building a wide variety of custom light fixtures to the specifications of interior designers and architects. But after a few years, “I got this deep yearning to make my own work that would be completely to my own aesthetic,” she says. Harnessing her creative impulses, she developed a series of large-scale “light sculptures” made from interlocking, irregularly shaped bronze or stainless-steel hoops lined with LEDs behind opal glass diffusers.

“The forms come to me in a very instinctive and spontaneous way,” says Barry, who is represented by New York’s Todd Merrill. “My initial rapid sketches have a quality of line to them that I love, and that’s something I try to emulate in the finished pieces.” After translating her drawings to digital files, she cuts the individual metal pieces (which can number 40 to 50 components for a single work) by water jet, and then welds them together and finishes each piece by hand. Recently, Barry has been experimenting with more jagged, rectilinear forms, which she says “feel far more masculine, dynamic and even aggressive.” Along the way, she is attracting an impressive range of high-profile clients, including Peter Marino, Kelly Hoppen and Sylvester Stallone.