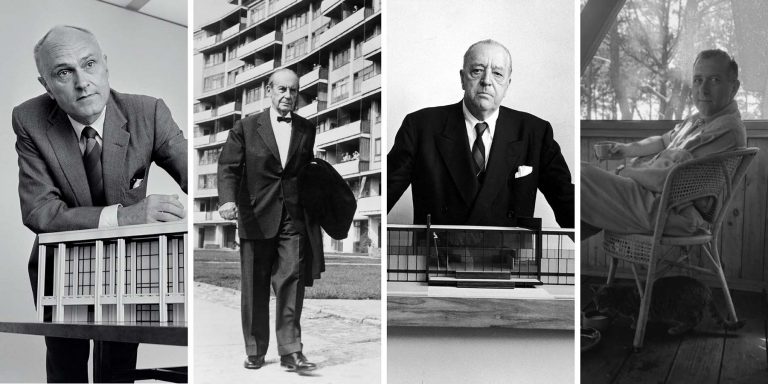

April 28, 2019A new show at Chicago’s Matthew Rachman Gallery through July 21 looks at the legacy of Mies van der Rohe — seen above peering through a model of the Windy City’s 860–880 Lake Shore Drive towers (photo by Frank Scherschel/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images). Top: The gallery’s installation centers on a trove of original blueprints, including plans for 111 E. Wacker and One Charles Center, displayed with such works as an MR chaise. All photos by Nathaniel Smith, courtesy Matthew Rachman Gallery unless otherwise noted

Less is more,” that inescapable quote attributed to Mies van der Rohe, has long been modernism’s tagline. But when it comes to this year’s observances of the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus, where Mies was the final director, more is more. Two new museums are opening in Germany dedicated to the history and legacy of the forward-looking art and design institution. And special exhibitions are popping up from São Paolo to Tel Aviv that shine a spotlight on its faculty and students, who broke the barriers between artist and artisan, articulated a new partnership of form and function and reshaped the built environment. Of particular note is “Mies van der Rohe: Chicago Blues and Beyond,” running through July 21 at the Matthew Rachman Gallery in Chicago, where the designer settled after leaving Germany.

The Nazis closed the Bauhaus in 1933, but Mies soldiered on in Berlin for another five years before emigrating to the U.S., where, in 1938, he became director of the school of architecture at Chicago’s Armour Institute, now the Illinois Institute of Technology, or IIT. From this academic perch, he profoundly influenced the course of architectural practice internationally. And from his own drafting table, he changed the look of his adopted city, completing such now-iconic projects as the 860-880 Lake Shore Drive apartment towers, the Chicago Federal Center and One IBM Plaza, as well as the IIT campus.

The show includes a Barcelona chair with a prototype cushion that Mies designed for his towers at 860–880 Lake Shore Drive. The chair, as well as never-before-seen ephemera, is on loan from T. Paul Young, an architect who worked in Mies’s studio.

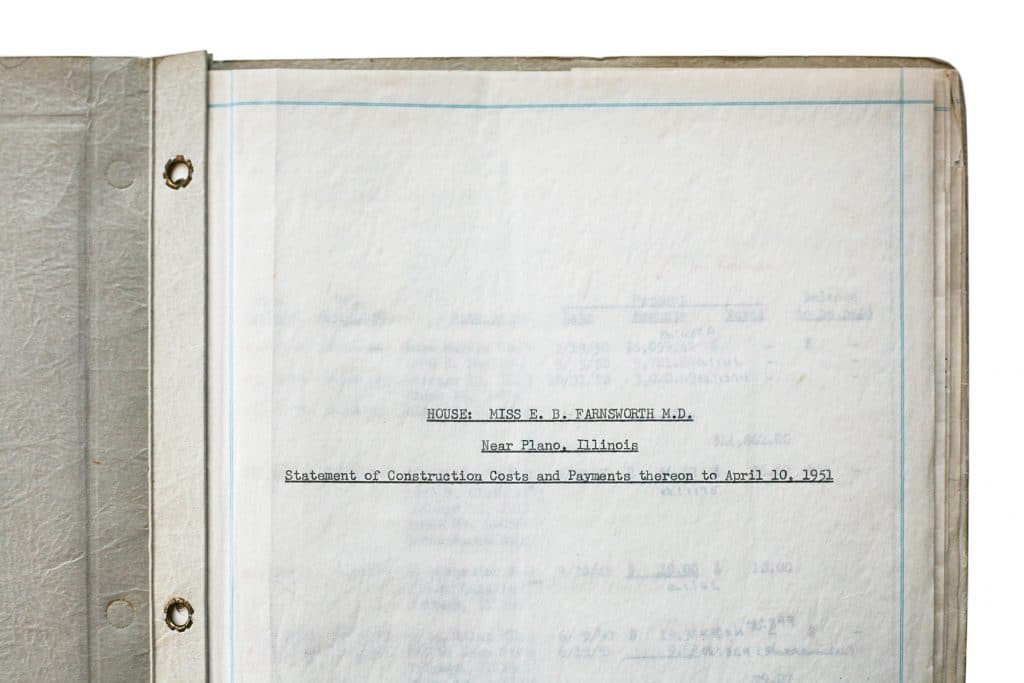

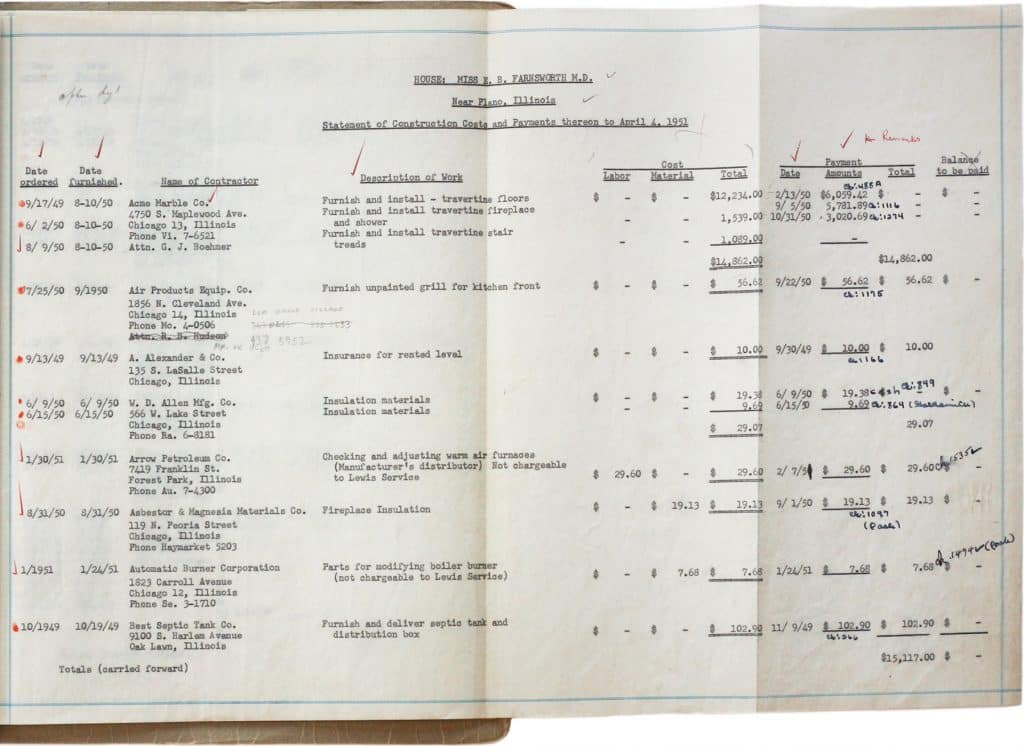

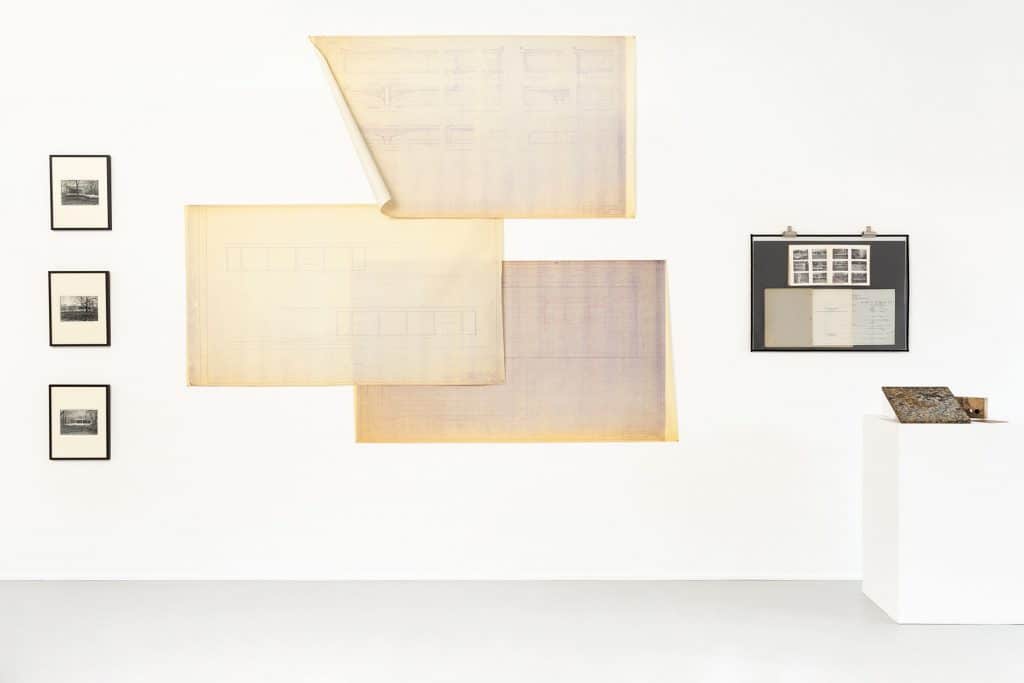

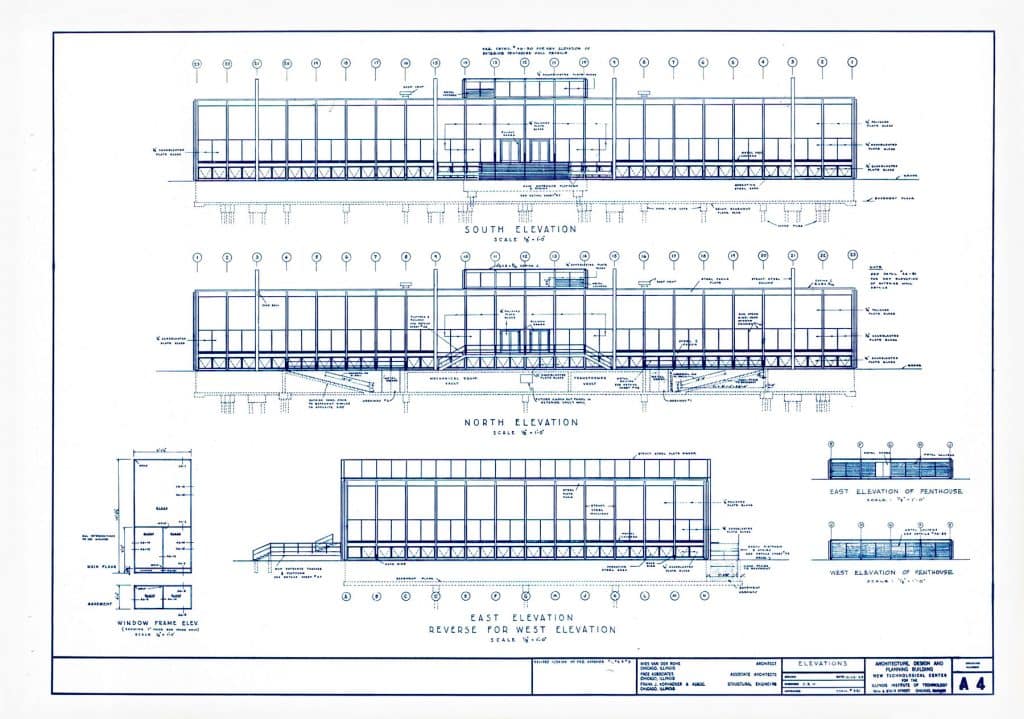

Rachman — who last year mounted a show of works by Charlotte Perriand focused on Les Arcs, the ski resort she designed in the French Alps — has previously hosted two benefits in support of Mies’s Farnsworth House. (The “Chicago Blues and Beyond” opening, with architect Dirk Lohan, Mies’s grandson, on hand, was also a fundraiser for the Farnsworth House, which has been a house museum owned and operated by the National Trust for Historic Preservation since 2003.) With the Bauhaus anniversary approaching, he decided to build an exhibition around a cache of the designer’s blueprints he acquired several years ago. Now for sale, the blueprints are actual working documents used by junior and senior architects in Mies’s office. Some have never before been seen publicly.

A dozen clipboards hold working documents and correspondence related to the studio’s projects.

Mies used these textile samples when designing the interiors of the Arts Club of Chicago in the early 1950s.

Among the plans, examples of which measure as large as 48 by 32 inches, is one for the Barcelona chair, done for the Wells Furniture Company, which manufactured the piece in the 1930s before Knoll began production. There are also drawings for architectural projects, including One Charles Center and the Highfield House condominium, both in Baltimore; 111 E. Wacker Drive, in Chicago, now home to the Chicago Architecture Center; and IIT’s Crown Hall, whose massive, column-free span epitomizes Mies’s embrace of utterly adaptable, universal space. It was built to house the Department of Architecture and Institute of Design.

These projects represented a leap forward in the architect’s career, an opportunity to build at a scale he had only imagined before the war. Advances in technology, access to materials and the willingness of American developers and corporations to get on board with modern design propelled him to a period of great creativity and success.

Rachman has taken a contextual approach to his installation of the blueprints on offer, interspersing the display with furniture and ephemera, much of it on loan from architect T. Paul Young, who at 17 became an office boy in Mies’s firm. “I’d pick up his cigars at Dunhill, organize files, things like that,” recalls Young, who advanced through the ranks to work on structures like the unrealized Mansion House Square, in London (his last project at the firm). “The office had a studio atmosphere, and there were long racks of blueprints of all of Mies’s projects. All the architects in the office would use those as reference. If they were designing louvers or a curtain-wall detail, they would be able to look at other buildings to see what was done and make it even better.”

The cover for the original sales brochure for 860–880 Lake Shore Drive — which is in the exhibition as well — touted the fact that the residences provided “Mutual Ownership Offering Stability at the Lowest Possible Cost.”

Among the materials from Young’s archive in the show are fabric swatches from the Farnsworth House and Mies’s sole interior-only project, the Arts Club of Chicago (razed in 1995); a rare bronze-frame version of the Brno chair manufactured by Brueton; a sales brochure for the 860-880 residences (“Mutual Ownership Offering Stability at the Lowest Possible Cost”); construction documents; and images produced by Hedrich-Blessing Photographers, the renowned architectural photography firm founded in Chicago in 1929. In addition, Rachman has on display and for sale two key pieces of furniture: an MR chaise longue, circa 1970, reupholstered in Brazilian cowhide but retaining the original strapping; and a Barcelona couch. “We want people to see the different materials Mies used and to better understand these pieces — which they have seen many times in various settings — within the bigger picture of Mies’s work,” says Rachman.

Although later, less artful interpretations of the architect’s aesthetic contributed to the perception of modernism as manipulative and soulless (a critique initially applied to the master’s own work), he remains a giant in the history of the built environment, a man whose philosophy is, perhaps, as significant as the structures he designed. “In 1939, Mies gave a lecture to students in which he discussed designing a house,” notes Young, who serves as executive director of the Bauhaus Chicago Foundation. “He said that coming to the house, the front door, was the most important thing to consider. And as he concluded, he said, ‘The house is really the shell, and the life lived therein, is the bloom.’ And that was true whether he was designing a home or an office building or Crown Hall. He was setting a stage for living.”