July 16, 2014Britain’s preeminent folk-art dealer Robert Young is known for his art-historical chops and his jolly, open demeanor. Top: Among the unusual finds at Young’s eponymous shop: a dozen sailor’s “fids,” from around 1780, once used for splicing rope and knots and now enjoying a second life as decorative pieces.

When the London dealer Robert Young went into the business of selling British folk art, in 1976, no one knew what he was talking about. “The field didn’t exist,” the now-renowned specialist in the subject recently recalled. “There was no market at the time. I started with eight-hundred pounds and a secondhand van.”

He began by buying what no one else wanted: primitive country objects like dug-out chairs, old fruit baskets, painted marriage cupboards, worn tavern tables, tobacco boxes and homemade toys. With his intense curiosity, enthusiasm and signature charm, he persuaded families to let him go through their barns and sheds, extracting heirlooms never regarded as such. It probably helped that he is a big, jolly man, a delightful storyteller with a wide smile, endearingly unkempt hair and twinkling blue eyes.

Building up a stock of art and furniture from all over the British Isles, and finding buyers from America and the Continent, he eventually created a whole new market. At first, however, he couldn’t even afford to rent a shop. “I sold everything I found to the trade,” he says. Finally, in 1978, he opened a tiny gallery in Battersea, South West London, just over the bridge from the Kings Road in Chelsea. But even then, he says, “I struggled.”

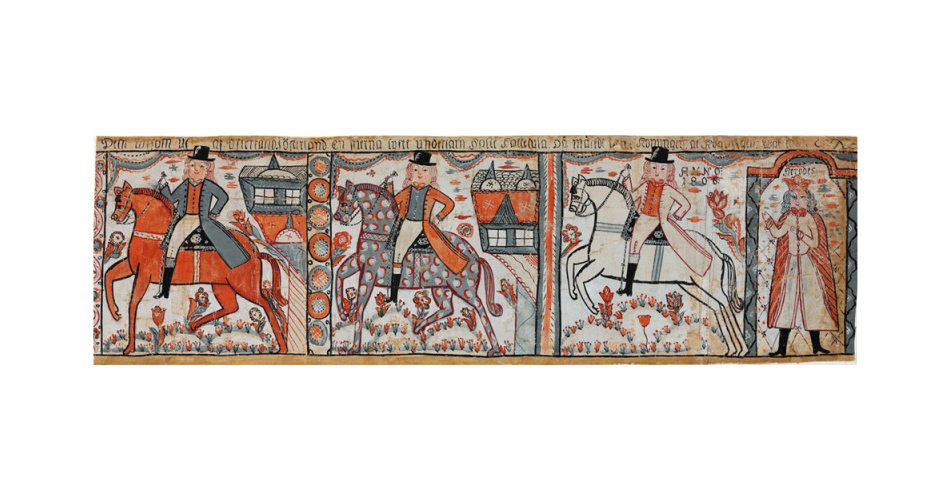

Things have certainly changed since then: On June 10, the Tate Britain opened the first-ever major survey of British folk art, featuring furniture, ship figureheads, embroidery, carousel horses and works of art by untrained talents. Young has lent seven pieces to the show, including pictures by George Smart, a 19th-century rural English tailor who created portraits of his neighbors by piecing together fabric remnants, a bit like a jigsaw puzzle, on top of prints of landscapes.

Today, as the Tate show demonstrates, and as one can tell from Young’s gallery on Battersea Bridge Road, directly in front of the new Royal College of Art, the dealer’s specialty is a hot commodity. He designed the 650-square-foot gallery himself, creating something so beautiful that clients have since asked him to decorate their homes in similar taste. (To meet these requests, he and his French wife and business partner, Josyane, opened a “design consultancy” they call Rivière Interiors in the mid-1980s.)

A well-worn circa-1800 wooden rocking chair exemplifies the kind of primitive country furniture that Young has collected for decades. The folk art horse sculpture dates from the same time and hails from Sweden.

“Folk art is difficult to define, but if you put five things in a row and ask anyone which is folk art, they all pick the same thing,” says Young, who ticks off a litany of objects that comprise the category: country-style homemade furniture, weather vanes, baskets, crockery, leather goods, toys, textiles, decoys and more.

Once he spots something he loves, like an early Windsor chair or a Noah’s ark toy, Young has very specific criteria for purchasing it: “A piece must be un-interfered with,” he explains. “It should still be in its original condition but show what has happened to it. Its history has redefined it as an object.”

He says he wrote his book, 1999’s wonderfully revealing Folk Art (Mitchell Beazley), to help people interested in the category to understand this — to “discover both the qualities that reflect the makers’ vision and the qualities lent by time and nature.” Those latter attributes include crusty original paint, copper covered in verdigris and a chair whose rails are worn smooth and thin from use.

Young came to antiques dealing quite naturally. “I’ve never done anything else,” he says. “As a schoolboy I wanted to be a painter. I went to the Sorbonne to study and take drawing classes and realized I wasn’t that good. Then I thought, ‘I’ll be an art dealer,’ and so I went knocking on doors to get a job at a gallery. I was twenty years old.”

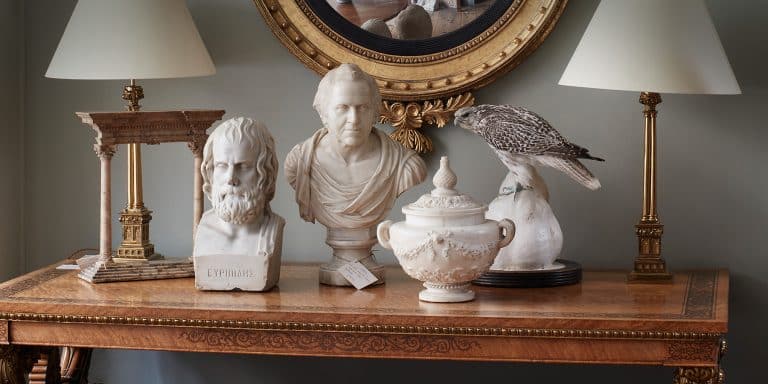

His first job in the field was for Frank Berendt, a London dealer who sold French court furniture to places like the Getty. “He was immaculate. I was a ragamuffin,” Young recalls. “He gave me tutorials at teatime. He knew I knew nothing. He taught me the five most important rules for any dealer: Look for rarity, quality, condition, provenance and a good price, i.e., don’t pay too much.”

A hand-carved English pigeon decoy, circa 1880, with a distinctive red breast, faces a circa-1900 working shorebird decoy, likely French, with a massive architectural sconce in the background, made of copper with a rich verdigris patina.

Finding Young promising, Berendt helped him get a spot in the Sotheby’s works of art training program, where he learned under its notoriously tough director of studies, Derek Shrub. “I was surrounded by all Oxbridge types and was hugely underqualified,” Young remembers. “But, thankfully, Shrub wasn’t the academic type. He told us, ‘This is all about your eyes; I don’t care who Charles II was.’ ”

There were constant tests, and Shrub kicked out students as the weeks went by. Young, however, persevered. Now, nearly 40 years later, he is one of the most popular and respected dealers in London. The bible of good decorating taste, World of Interiors, has written him up, as have several American magazines. He participates in top fairs, including New York’s Winter Antiques Show, for which he serves as co-chair of the vetting committee.

In addition to contributing to the show at the Tate Britain, Young has just mounted his 14th annual exhibition of British and European folk art at the gallery and produced a fully illustrated accompanying catalog. “We collect works throughout the year for this show,” he explains, “and we install it in compelling compositions, to celebrate the unique, inherently artistic and sculptural qualities of great historic handmade objects.

“These are not things that were made as treasures,” Young continues, waxing philosophical about the subject that has become his life’s passion. “Folk art can be anything, even a watering can. We don’t mind what it is, but the object has to have integrity and a fundamental honesty. It has to be strong, to have a place in the art-historical narration.”

“It has to have merit,” he says by way of conclusion. “And it’s that subjective element that is so important.”

Visit Robert Young Antiques on 1stdibs