July 11, 2016“This Is a Portrait If I Say So: Identity in American Art, 1912 to Today,” at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, in Brunswick, Maine, examines the unconventional ways that artists have re-conceptualized the portrait through works such as Gerald Murphy’s Razor, 1924 (above), and Robert Rauschenberg‘s Self-Portrait, 1964 (top). Art © Estate of Honoria Murphy Donnelly/Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York

The portrait is about as traditional a mode of expression as it gets. Artists have been making a living by attempting to capture the likenesses of their patrons for millennia, from busts of emperors to gleaming oils of aristocrats. But the portrait has also yielded some shockingly radical moments in modern and contemporary art history. Many of those moments have been brought together for the first time in “This Is a Portrait If I Say So: Identity in American Art, 1912 to Today,” a gem of an exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, in Brunswick, Maine, on view through October 23.

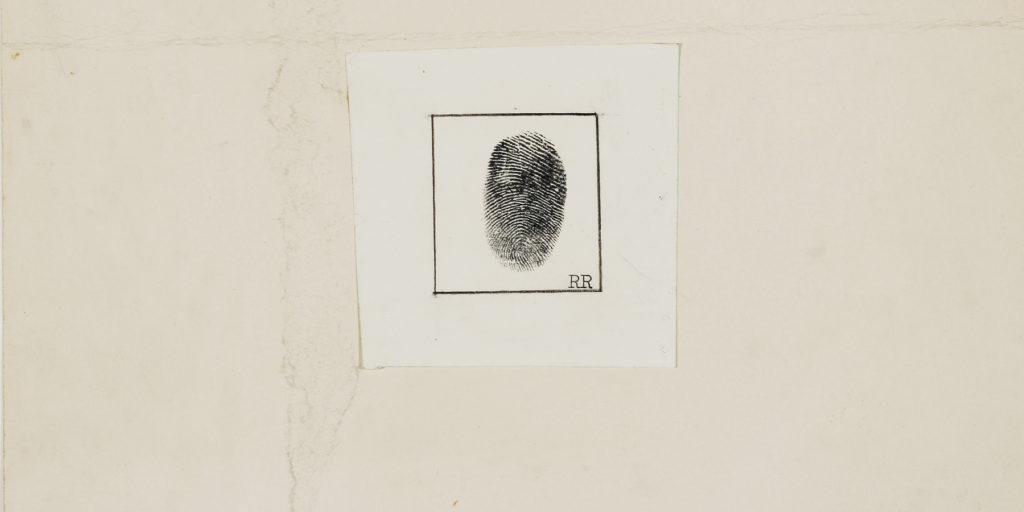

At the heart of the show is the understanding that personal identity is far more nuanced and complex than one’s appearance could ever reveal. But that revelation poses an obvious problem when it comes to portraiture. The 60-odd works in “This Is a Portrait” — comprising numerous loans, both national and international, as well as highlights from Bowdoin’s own collection — don’t necessarily try to offer more insight into a sitter’s identity than a conventional portrait might (although often they do). Rather, by using other means of capturing sitters or themselves — whether symbolic, abstract, conceptual or indexical (a thumb print, for example) — the artists included here show that personal identity is a slippery thing and that straightforward representation offers very little when it comes to understanding it.

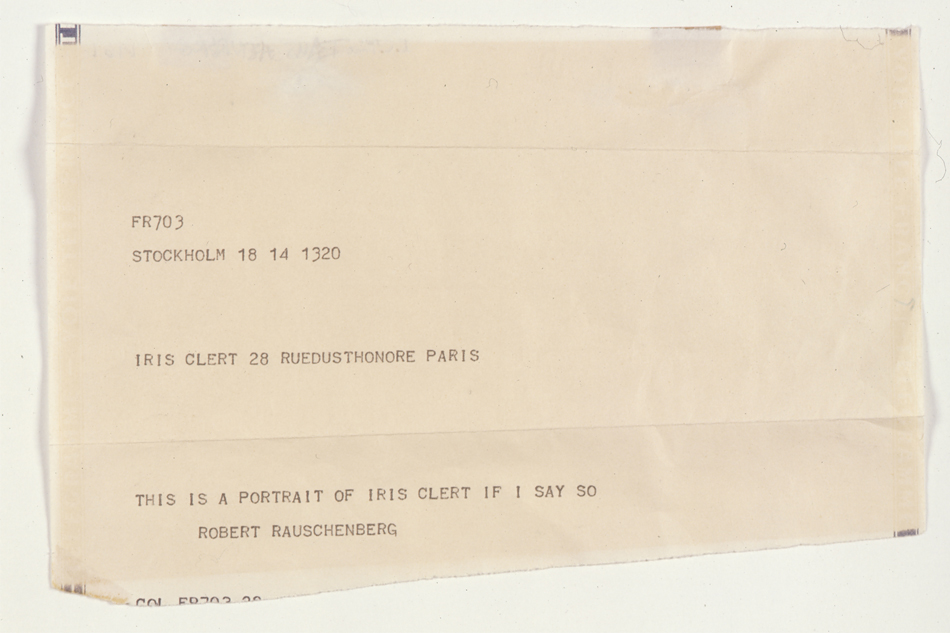

The exhibition takes its name from a portrait Robert Rauschenberg created in 1961 of his Paris dealer, Iris Clert, consisting of a telegram bearing the brief missive THIS IS A PORTRAIT OF IRIS CLERT IF I SAY SO. It was the artist’s contribution to a show on portraiture at Clert’s gallery and a groundbreaking gesture that sets the tone for Bowdoin’s exhibition. “Rauschenberg has clearly been so instrumental in rethinking what a portrait could be,” says Anne Collins Goodyear, codirector of the Bowdoin Museum, who organized “This Is a Portrait” in collaboration with Jonathan Frederick Walz, of the Columbus Museum, in Columbus, Georgia; and independent curator Kathleen Merrill Campagnolo. “In so many ways it’s what our thinking revolved around.”

Mel Bochner‘s textually descriptive painting Self / Portrait, 2013. Collection of the artist, New York, NY, MB3-490. Copyright Mel Bochner

It’s not surprising, then, that the show’s checklist includes some of art history’s greatest rabble-rousers, like Marcel Duchamp, who’s represented by a 1961 edition of his Boîte-en-Valise (box in a suitcase), which opens to reveal miniature reproductions of his own work. “He really revolutionized identity, and in reinventing the artwork, he also reinvented the ways we can describe the self or even think about the self,” says Goodyear.

The curators divided the show in a somewhat unorthodox manner, homing in on three distinct periods of American art making: the 1910s and ’20s, the early 1960s to ’70 and the 1990s through today. “These were periods when there were artistic breakthroughs — like the invention of abstraction and conceptual art — accompanied by political events that have reshaped the way that people see the world and their place in it,” explains Goodyear.

The 1940s and ’50s were deliberately excluded because “Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting were emphatically not about portraiture,” she continues. “We really only wanted works that had an interest in saying something about biography or autobiography.” It was also important to the curators that the artists be American, or have a connection to the United States. “There is something about the ethos of ‘American-ness’ that is associated with being self-made, and one can be American without having grown up out of the soil of this place,” Goodyear adds. “I think there is also an idea of a clean slate — of abandoning the ghosts of Europe.” The chosen pieces say something as well about the nature of American identity and how it’s susceptible to reinterpretation, even reinvention — a condition critical to considering how slippery identity is in the first place.

The selection is surprisingly cohesive. Jumping decades enabled the curators to draw connections between older and more-recent works that might not have been so obvious otherwise. We can trace the use of text as a means of portrayal from Gertrude Stein’s 1909 poem-portrait of Pablo Picasso to Rauschenberg’s 1961 telegram, to Glenn Ligon’s 1991 self-portrait Untitled (I am an invisible man), to Mel Bochner’s 2001 circular-text rendering of the late sculptor Eva Hesse.

Personal identity is a slippery thing, and straightforward representation offers very little when it comes to understanding it.

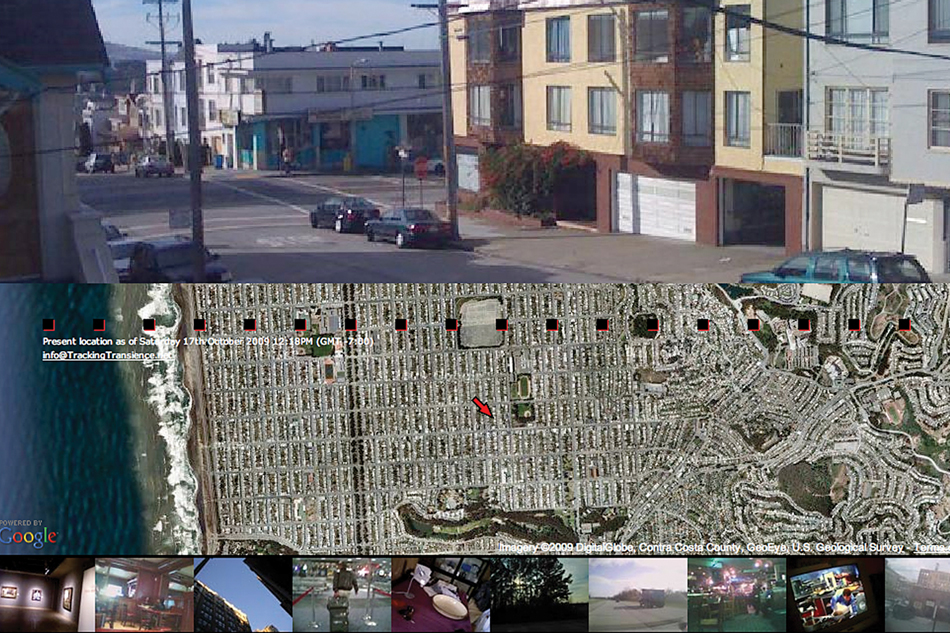

Installed together in the museum are (left to right) Eleanor Antin‘s exercise-bike assemblage Yvonne Rainer, 1971; Rauschenberg’s wall-based Autobiography, 1968; Antin’s Carolee Schneemann, 1970; Walter De Maria’s steel Cage II, 1965; and Jim Dine‘s Isometric Self-Portrait, 1964. Photo by Dennis and Diana Griggs/Tannery Hill Studio, courtesy of Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Marsden Hartley’s Portrait, ca. 1914–15, is a remembrance of his close friend and possible lover Karl von Freyburg, a Prussian officer killed at the onset of World War I. © Marsden Hartley

It’s difficult not to notice that many of the works on view here are portraits of artists. “The notion of friendship and mutual support for radical experiment with artistic creation is definitely one of the subtexts of this show,” Goodyear says. Charles Demuth depicted Marsden Hartley (circa 1923), Arthur Dove (circa 1924) and Wallace Stevens (1925–26) in sketches that combine the artists’ written names with imagery they might have used. Walter de Maria represented John Cage in 1965 through a minimalist stainless-steel “cage,” and Eleanor Antin captured Carolee Schneemann and Yvonne Rainer (among other women artists) in 1970. Robert Indiana summed up Hartley in 1990 by invoking a famous portrait that the latter made decades earlier, while Ben Benn represented the same painter by imitating his style.

For his part, Hartley pictured Gertrude Stein (1916) in one portrait and, in another, his close friend and possible lover Karl von Freyburg (1914–15), a Prussian officer killed at the onset of World War I. It’s one of the more recognizable images in the show.

Hartley layered formal patterns and symbols (numbers, flags, crosses) in arrangements that must have seemed as radical a portrait in his day as Glenn Ligon’s “Runaways” series did in 1993. The suite of 10 lithographs mimic 19th-century ads printed by slave owners to track down runaway slaves, pairing woodcut images with written descriptions. For the texts, Ligon asked friends to describe him as they might in a missing-person report. The descriptions vary widely, calling attention to how heavily one’s identity relies on the perceptions of others. And the viewer’s interpretation of the descriptions complicates the situation even more.

Such interactions between maker, viewer and art are distinctly 20th and 21st century, continuing a phenomenon sparked, in part, by Duchamp, who looms large over the entire exhibition. His Boîte-en-Valise, says Goodyear, “presents one of the key ideas of the twentieth century — that the viewer has a critical role to play as interpreter of a work. That really helps break down the notion that there is any one essential way to understand anyone.”