July 13, 2015The bejeweled Holy Thorn Reliquary, ca. 1395, is among the Renaissance treasures comprising the Waddesdon Bequest, once assembled by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild and now on view in a new gallery at the British Museum. Top: The Ghisi Shield, ca. 1600, is one of only two surviving works of damascened metalwork by Giorgio Ghisi. All photos © The Trustees of the British Museum

The legendary 18th-century German banker Mayer Amshel Rothschild passed on to his descendants a genius for making money and a passion for amassing treasure. Among the most notable of his descendants’ treasures is the spectacular collection of 265 Renaissance jewels and objects assembled by his grandson Anselm, and Anselm’s own son Ferdinand, who became a British subject and a Liberal MP. When Baron Ferdinand died in 1898, he left this collection to the British Museum, where he was also a trustee. Known as the Waddesdon Bequest, it was then the most valuable gift in the museum’s history and remains among the most important. Now, more than a century after its arrival in Bloomsbury, it is time to celebrate again. The fabulous jewels, finely painted majolica, intricate boxwood carvings, richly colored Limoges enamels, fantastical objects in silver gilt, gold, amber and rock crystal have been installed in a new gallery where they look more splendid than ever.

Moved from a cramped space tucked away in the European galleries, the collection now resides in a spacious new gallery carved out of the old Reading Room near the museum’s imposing main entrance. The London-based architecture firm Stanton Williams has created a superb showcase that is modern, edgy and luminous. Three large freestanding, slant-fronted glass cases housing the larger treasures occupy much of the central space; smaller objects are shown off in vitrines built into the walls. In a transparent tower, the exquisite Holy Thorn Reliquary sits in splendid isolation. Made for Jean, duc de Berry around 1400, this bejeweled object, standing at one foot high, is comprised of many beautifully enameled gold figures of angels and saints. They rise from a golden castle to surround a small container housing a thorn said to have come from the crown worn by the crucified Christ. The work is glorious.

The Lyte Jewel, made of enameled gold set with diamonds, 1610, was commissioned by King James I of England to give to his friend, Thomas Lyte. The locket contains a portrait by Nicholas Hilliard of the king.

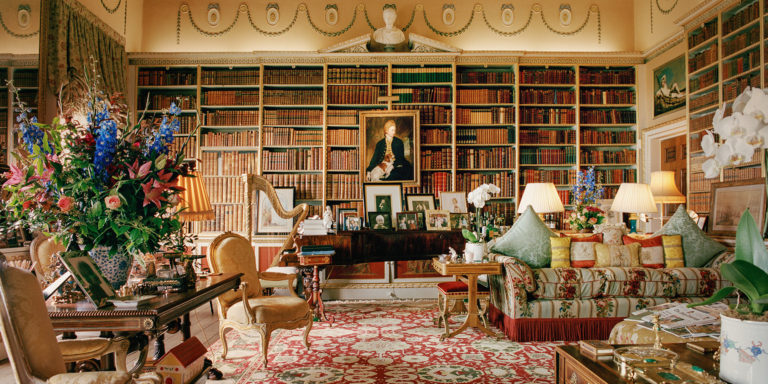

The collection takes its name from Waddesdon Manor, Ferdinand Rothschild’s grand 19th-century English country house. Modeled on a French Renaissance chateau, it contains interiors decorated in high 18th-century style, featuring ormolu-mounted furniture, Sèvres porcelain, paintings by Canaletto and Boucher, Savonnerie carpets and walls hung with fine silks and tapestries. In dramatic contrast, Ferdinand turned his Smoking Room, to which he and his male guests retreated after dinner, into a Buckinghamshire Kunstkammer, echoing the Renaissance wonder cabinets that advertised and enhanced the power of princes — as it did his.

For anyone familiar with the old gallery, the generous proportions of the new space, combined with the lighting and the drama of the display, may cause them to feel they are seeing many objects for the first time. The growing interest in Kunstkammer collecting is bound to get a big boost too. After all, what ignited Baron Ferdinand’s passion for Renaissance marvels was his exposure to the treasure cabinets of his own relations.

He and his cousins were at the core of a robust market for Renaissance jewels and objects. They learned from one another’s acquisitions and competed to nab the best. Demand outstripped a limited supply. It was fertile ground for forgers. The Baron, although knowledgeable and canny, did not escape being hoodwinked, nor did his kin. “A Rothschild provenance may be highly desirable but it does not guarantee of authenticity,” observes the decorative arts scholar Charles Truman in his catalogue of the Renaissance jewels in the Metropolitan Museum’s Robert Lehman collection.

The British Museum’s new installation does not hide the fact that Baron Ferdinand was sometimes duped, as it mixes the known-forgeries in with the authentic pieces. In some cases, you have to read the labels to distinguish one from the other. At least once, though, criminal activity worked to the great advantage of the Waddesdon Bequest. In 1860, the Holy Thorn Reliquary, which then belonged to the Imperial Treasury in Vienna, was sent to the legendary goldsmith Salomon Weininger for repair. Secretly Weininger had it copied, then returned the forgery to the Treasury and kept the original for himself. Within a decade it was bought by Anselm Rothschild. Today, it is one of the jewels in the crown of Ferdinand’s Bequest.