October 28, 2014One of the most recognizable works by Matisse in the show, Blue Nude II, 1952, stands out for its use of just one color. Top: A view of the exhibition at MoMA (photo by Jonathan Muzikar © 2014/MoMA). (All other images © 2014 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, unless otherwise noted)

Earlier this month, the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, unveiled “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs,” a show that promises to be a legendary blockbuster by the end of its run on February 8, 2015. The largest exhibition ever of Matisse’s late work, it focuses on his so-called “cut-outs” — vibrantly colored works made from painted paper, cut into shapes by the master’s own hand and assembled into compositions by his assistants. Matisse referred to this practice, whose aesthetic lies somewhere between mural, bas-relief and painting, as “drawing with scissors.” The show includes about one hundred such works, mostly created between 1937 and 1954 and drawn from public and private collections around the world, as well as drawings, illustrated books, textiles, stained glass and films of the artist at work.

At London’s Tate Modern, where the show was organized by Sir Nicholas Serota, the Tate’s director, among others, it drew more than 560,000 people between April and September, becoming the most popular exhibition in the museum’s history. Yet MoMA’s version may go one better. As well as being the institution’s first extensive display of the cut-outs since 1961, the exhibition also includes The Swimming Pool, the room-size frieze of abstracted blue swimmers frolicking in water that Matisse created in 1952, two years before his death, for the dining room of his apartment at the Hôtel Régina in Nice. Although MoMA acquired this large and ambitious work in 1975, it hasn’t been on display for about 20 years, largely due to its deteriorating condition; prior to this show, it had been in conservation since 2008, with Karl Buchberg, the museum’s senior conservator, overseeing its rehabilitation.

The Parakeet and the Mermaid, 1952, can be seen in MoMA’s show of Henri Matisse’s cut-out works.

The conservation of this work was the genesis of our exhibition,” says Jodi Hauptman, senior curator in the department of prints and drawings, who organized the show’s New York iteration together with Buchberg and Samantha Friedman, an assistant curator in her department. “This is also the first time in the history of MoMA that an exhibition has been a collaboration between a curator and a conservator.”

Here, Hauptman talks about the show and how working on it illuminated her understanding of Matisse.

Matisse created Creole Dancer, 1950, in a single day, basing the image off sketches he made of a dancer he invited to perform in his studio.

How does MoMA’s show differ from the Tate’s version?

A big difference is the inclusion of The Swimming Pool, which is the conceptual heart of our project. And because of Karl’s involvement, our exhibition has a real materials-and-methods focus. We used the work as a lens through which to see Matisse’s practice.

You have also included more drawings. Why is that?

The myth about Matisse is that he cut freehand with the scissors. We’ve included the two film clips that show Matisse cutting and moving his scissors through the paper with great ease. But after looking into this a bit more, we discovered that in many cases he was always drawing. He might draw a form again and again, learning it before he cut. We’ve included drawings related to the cut-outs, so viewers will be able to see this preparatory work.

What about the other oft-told tale about Matisse and the cut-outs, that he made them because he was too old and feeble to paint?

That’s not the story we tell. Yes, he was not a sprightly 20-year-old anymore. But we think this was a moment when he was at the height of his creative powers, inventing a new form. He was still drawing. He was still making paintings. But this practice really captured his imagination. It addressed certain challenges that he struggled with throughout his career, like the eternal conflict between line and color. With cut paper he was able to cut directly into color. The cut was the line.

Another thing we’ve focused on is scale. When Matisse begins making the cut-outs, he’s cutting paper and composing on a board that can fit on his lap or his desk. As his ambition for the work grows, he begins to compose directly on the wall. The walls don’t have a boundary the way an easel picture does, and the cut-outs allowed his ambitions to spread. You’ll physically feel this shift in the show. So it’s impossible to think this is a person who is unable to work.

Why do these works have such a strong popular appeal?

There’s just something about the reduction of a form to its essentials, in combination with this radiant, luminous color. It gets at something that’s seemingly simple but deeply complex, whether it’s the relationship between colors or the small decisions in the composition. Also the materiality, and the relationship among colors, is so vibrant in person. In Matisse’s studio these works were simply pinned to the walls, so the paper would curl and droop and flutter. When they left the studio they were usually mounted, so they lost some of that freedom. But when you see them in person, you still see some of the curvature, the layering, the sculptural nature of the work. Matisse himself said that it reminded him “of the direct carving of sculptors.”

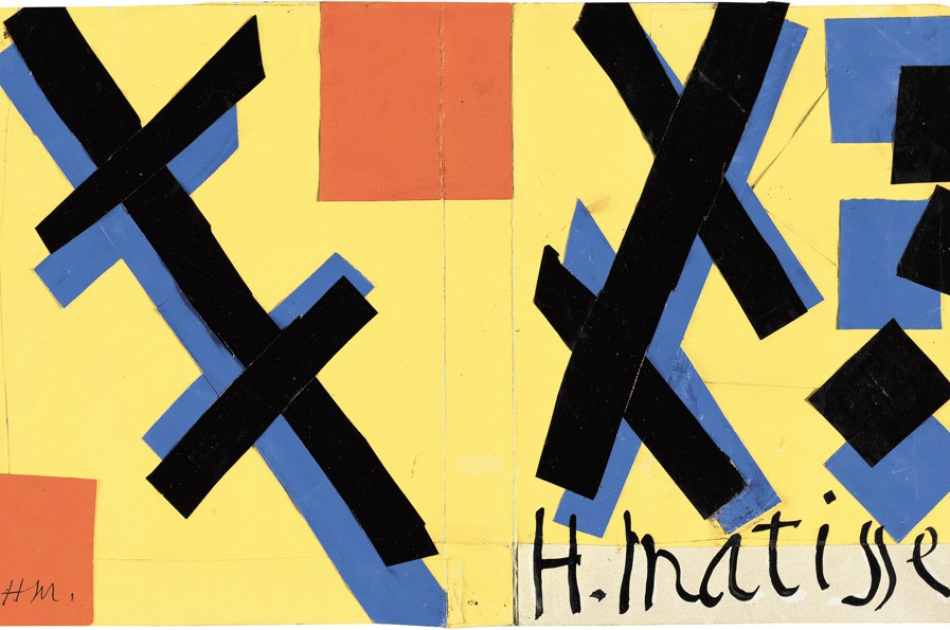

A display case contains pages from the artist’s 1947 illustrated book, Jazz, and the digital display lets visitors virtually flip through the entire book. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar © 2014/MoMA

What was the most surprising thing you learned about Matisse while organizing this show?

How engaged he was with his own studio space. Because of The Swimming Pool, we had a sense from the beginning that he was interested in creating an environment. But it wasn’t until we dug in and really began looking at photographs that we saw how these works were in constant flux. Forms would migrate within a composition. Or a composition might be vertically stacked, and then you see a photograph taken three months later, and it’s horizontal — and then it changes again. For me, it was really fascinating to see the multiple pinholes, which are a record of that process.

I’d encourage viewers to look closely for those pinholes. There’s that famous Matisse quote, “What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity…something like a good armchair.” But what you see with the pinholes is that there was labor. Even in a work that seems like a simple leaf on a colorful background, you see multiple pinholes, so you know he was moving it around.

The works dazzle with their colors, shapes and, in the case of Large Decoration with Masks, 1953, at right, their enormous scale. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar © 2014/MoMA