Items Similar to Japanese Children with Tortoise

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 5

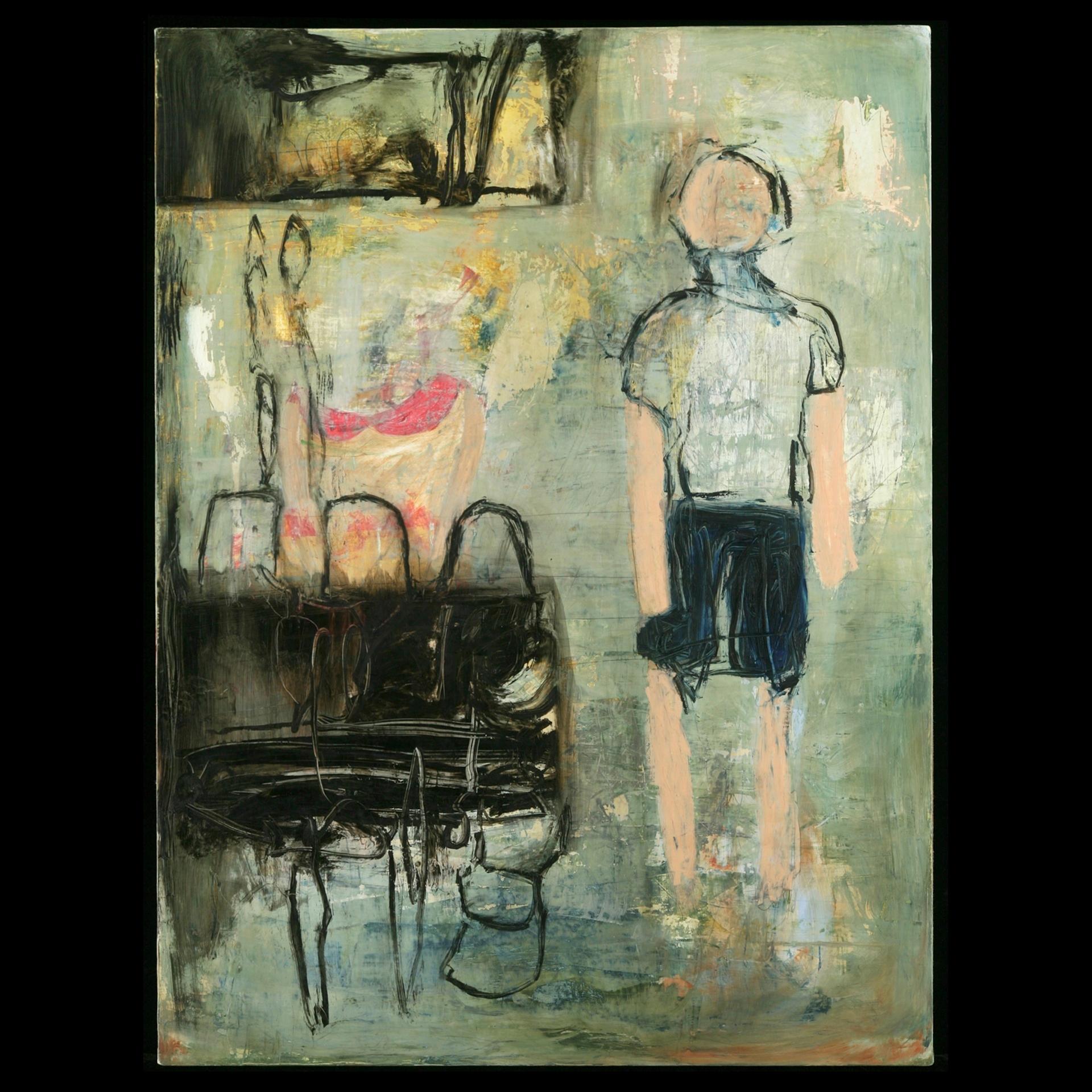

Harry Humphrey MooreJapanese Children with Tortoise1881

1881

About the Item

Harry Humphrey Moore led a cosmopolitan lifestyle, dividing his time between Europe, New York City, and California. This globe-trotting painter was also active in Morocco, and most importantly, he was among the first generation of American artists to live and work in Japan, where he depicted temples, tombs, gardens, merchants, children, and Geisha girls. Praised by fellow painters such as Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent, and Jean-Léon Gérôme, Moore’s fame was attributed to his exotic subject matter, as well as to the “brilliant coloring, delicate brush work [sic] and the always present depth of feeling” that characterized his work (Eugene A. Hajdel, Harry H. Moore, American 19th Century: Collection of Information on Harry Humphrey Moore, 19th Century Artist, Based on His Scrap Book and Other Data [Jersey City, New Jersey: privately published, 1950], p. 8).

Born in New York City, Moore was the son of Captain George Humphrey, an affluent shipbuilder, and a descendant of the English painter, Ozias Humphrey (1742–1810). He became deaf at age three, and later went to special schools where he learned lip-reading and sign language. After developing an interest in art as a young boy, Moore studied painting with the portraitist Samuel Waugh in Philadelphia, where he met and became friendly with Eakins. He also received instruction from the painter Louis Bail in New Haven, Connecticut. In 1864, Moore attended classes at the Mark Hopkins Institute in San Francisco, and until 1907, he would visit the “City by the Bay” regularly.

In 1865, Moore went to Europe, spending time in Munich before traveling to Paris, where, in October 1866, he resumed his formal training in Gérôme’s atelier, drawing inspiration from his teacher’s emphasis on authentic detail and his taste for picturesque genre subjects. There, Moore worked alongside Eakins, who had mastered sign language in order to communicate with his friend. In March 1867, Moore enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, honing his drawing skills under the tutelage of Adolphe Yvon, among other leading French painters.

In December 1869, Moore traveled around Spain with Eakins and the Philadelphia engraver, William Sartain. In 1870, he went to Madrid, where he met the Spanish painters Mariano Fortuny and Martin Rico y Ortega. When Eakins and Sartain returned to Paris, Moore remained in Spain, painting depictions of Moorish life in cities such as Segovia and Granada and fraternizing with upper-crust society. In 1872, he married Isabella de Cistue, the well-connected daughter of Colonel Cistue of Saragossa, who was related to the Queen of Spain. For the next two-and-a-half years, the couple lived in Morocco, where Moore painted portraits, interiors, and streetscapes, often accompanied by an armed guard (courtesy of the Grand Sharif) when painting outdoors. (For this aspect of Moore’s oeuvre, see Gerald M. Ackerman, American Orientalists [Courbevoie, France: ACR Édition, 1994], pp. 135–39.) In 1873, he went to Rome, spending two years studying with Fortuny, whose lively technique, bright palette, and penchant for small-format genre scenes made a lasting impression on him. By this point in his career, Moore had emerged as a “rapid workman” who could “finish a picture of given size and containing a given subject quicker than most painters whose style is more simple and less exacting” (New York Times, as quoted in Hajdel, p. 23).

In 1874, Moore settled in New York City, maintaining a studio on East 14th Street, where he would remain until 1880. During these years, he participated intermittently in the annuals of the National Academy of Design in New York and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, exhibiting Moorish subjects and views of Spain. A well-known figure in Bay Area art circles, Moore had a one-man show at the Snow & May Gallery in San Francisco in 1877, and a solo exhibition at the Bohemian Club, also in San Francisco, in 1880. Indeed, Moore fraternized with many members of the city’s cultural elite, including Katherine Birdsall Johnson (1834–1893), a philanthropist and art collector who owned The Captive (current location unknown), one of his Orientalist subjects. (Johnson’s ownership of The Captive was reported in L. K., “A Popular Paris Artist,” New York Times, July 23, 1893.) According to one contemporary account, Johnson invited Moore and his wife to accompany her on a trip to Japan in 1880 and they readily accepted. (For Johnson’s connection to Moore’s visit to Japan, see Emma Willard and Her Pupils; or, Fifty Years of Troy Female Seminary [New York: Mrs. Russell Sage, 1898]. Johnson’s bond with the Moores was obviously strong, evidenced by the fact that she left them $25,000.00 in her will, which was published in the San Francisco Call on December 10, 1893.) That Moore would be receptive to making the arduous voyage across the Pacific is understandable in view of his penchant for foreign motifs. Having opened its doors to trade with the West in 1854, and in the wake of Japan’s presence at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, American artists were becoming increasingly fascinated by what one commentator referred to as that “ideal dreamland of the poet” (L. K., “A Popular Paris Artist”).

Moore, who was in Japan during 1880–81, became one of the first American artists to travel to the “land of the rising sun,” preceded only by the illustrator, William Heime, who went there in 1851 in conjunction with the Japanese expedition of Commodore Matthew C. Perry; Edward Kern, a topographical artist and explorer who mapped the Japanese coast in 1855; and the Boston landscapist, Winckleworth Allan Gay, a resident of Japan from 1877 to 1880. More specifically, as William H. Gerdts has pointed out, Moore was the “first American painter to seriously address the appearance and mores of the Japanese people” (William H. Gerdts, American Artists in Japan, 1859–1925, exhib. cat. [New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries, 1996], p. 5).

During his sojourn in Japan, Moore spent time in Tokyo, Yokohama, Kyoto, Nikko, and Osaka, carefully observing the local citizenry, their manners and mode of dress, and the country’s distinctive architecture. Working on easily portable panels, he created about sixty scenes of daily life, among them this vignette of a group of children enjoying themselves in a courtyard under the watchful eye of two women. According to Japanese custom, “All babies have their heads shaved,” as is the case with the infants in the arms of their mothers, one of whom lovingly rubs her toddler’s back (Celeste J. Miller, The Newest Way Round the World [New York: Calkins and Co., 1908), p. 259). The older boys, however, demonstrate their independence, two of them chatting with each other while a cohort teases a passing turtle, a traditional symbol of wisdom, patience, and longevity. Another boy sits slightly apart from the group, quietly observing the activities at hand.

That Moore should be drawn to the theme of child life is not surprising, for most Westerners found Japanese boys and girls to be both well-behaved and pleasing to the eye; as noted by Dorothy Menpes, daughter of the Australian painter, Mortimer Menpes, “I have never seen a child in Japan cry. . . . A group of Japanese children is perhaps the prettiest sight on earth, and they themselves are works of art, the beauty of which can scarcely be imagined. Each head and each piquant face is but a field where the ever-present artist can exercise his ingenuity and his skill in colour and design” (Dorothy Menpes, Japan: A Record in Colour by Mortimer Mempes, 5th ed. [London: Adam & Charles Black, 1902], p. 147).

Moore’s Japanese subjects have been described as being characterized by “strong and vivid color,” and Japanese Children with Tortoise is no exception, the rich palette, as well as the spirited brushwork, revealing the impact of Fortuny (“Oils by Humphrey Moore,” American Art News 18 [January 10, 1920], p. 3). At the same time, the lingering influence of Gérôme is apparent in the artist’s individualized portrayal of the sitters’ faces and clothing, as well their gestures and poses. His tightly cropped composition enhances the mood of familial intimacy, another key feature of this charming pictorial record of child life in late nineteenth century Japan.

Moore’s involvement with Japanese imagery emerged at a time when japonisme––a term first used in France in 1872 in reference to the impact of Japanese art, culture, and fashion on Western art––was becoming increasingly fashionable in European and American art circles. Robert Blum, Theodore Wores, Lilla Cabot Perry, and John La Farge were among the American artists who followed in Moore’s footsteps by traveling and painting in Japan. During the late-nineteenth century, other painters investigated Japanese themes too, but the majority did so within the confines of their studios, working from photographs or using imported artifacts and Caucasian models––which made Moore’s panel paintings, done in situ, all the more exceptional. In fact, treasuring them as souvenirs of his visit and realizing that they represented a way of life that was slowly disappearing, he refused to sell the series to the influential Paris art dealer, Goupil & Cie. Moore is also said to have turned down an offer of $1,000,000 from the financier, J. P. Morgan, although he ultimately agreed to relinquish three of his Japanese panels, selling one to the London art dealer, Sir William Agnew, and two to the prominent American expatriate art collector, William H. Stewart (Hajdel, p. 19). Moore kept the remainder for himself, installing them in his Paris studio in a “curious private collection that was covered at all times with a drape. Only intimate friends had the privilege of seeing this collection for which many people offered alluring sums” (Hajdel, p. 9; for a photograph of the installation, see Hajdel, plate III ).

Later in his career, Moore spent most of his time painting portraits of children and members of the European aristocracy, as well as likenesses of wealthy Americans, including the mother of William Randolph Hearst. He continued to reside in the United States until shortly after World War I, exhibiting his scenes of Japan at the Union League Club (1919) and the Architectural League of New York (1920), at which time they were praised for their “jewel-like quality of color” and “freedom and freshness of spontaneous workmanship” (as quoted in Hajdel, p. 17). A writer for the New York Sun described the works as “tiny affairs . . . packed with curious and attractive details. . . . It was a beautiful Japan that Mr. Moore discovered, and now many of the structures and much of the life that he recorded have changed, and not for the better, the artists say” (“Union League Club Begins Art Views,” Sun [New York], November 14, 1919).

After his death in Paris on January 2, 1926, Moore’s Japanese paintings remained with his second wife, the Polish countess Maria Moore, who later hid them from the Gestapo with the aid of a faithful servant. In 1948, the paintings were brought to the United States and exhibited in New York City in September of the following year. In the wake of that show, Eugene A. Hajdel (whose connection to Moore has yet to be determined) issued a thirty-three page booklet that provided details pertaining to the collection, as well as biographical information and a compendium of critical reviews on Moore––the only monographic treatment on the artist to date. Shortly thereafter, according to Gerald M. Ackerman, a prominent scholar of nineteenth-century French art, “Mrs. Moore and the whole collection simply disappeared” (Ackerman, p. 138). He also observed that although Moore’s Japanese subjects and his orientalist pieces have appeared on the art market now and again, for the most part, “they are rare” (Ackerman, p. 138).

- Creator:Harry Humphrey Moore (1844 - 1926, American)

- Creation Year:1881

- Dimensions:Height: 6.25 in (15.88 cm)Width: 10.9 in (27.69 cm)

- Medium:

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:New York, NY

- Reference Number:

About the Seller

5.0

Recognized Seller

These prestigious sellers are industry leaders and represent the highest echelon for item quality and design.

Established in 1952

1stDibs seller since 2010

32 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 10 hours

Associations

Art Dealers Association of America

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Ships From: New York, NY

- Return PolicyThis item cannot be returned.

More From This SellerView All

- Japanese Girl PromenadingBy Harry Humphrey MooreLocated in New York, NYHarry Humphrey Moore led a cosmopolitan lifestyle, dividing his time between Europe, New York City, and California. This globe-trotting painter was also active in Morocco, and most importantly, he was among the first generation of American artists to live and work in Japan, where he depicted temples, tombs, gardens, merchants, children, and Geisha girls. Praised by fellow painters such as Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent, and Jean-Léon Gérôme, Moore’s fame was attributed to his exotic subject matter, as well as to the “brilliant coloring, delicate brush work [sic] and the always present depth of feeling” that characterized his work (Eugene A. Hajdel, Harry H. Moore, American 19th Century: Collection of Information on Harry Humphrey Moore, 19th Century Artist, Based on His Scrap Book and Other Data [Jersey City, New Jersey: privately published, 1950], p. 8). Born in New York City, Moore was the son of Captain George Humphrey, an affluent shipbuilder, and a descendant of the English painter, Ozias Humphrey (1742–1810). He became deaf at age three, and later went to special schools where he learned lip-reading and sign language. After developing an interest in art as a young boy, Moore studied painting with the portraitist Samuel Waugh in Philadelphia, where he met and became friendly with Eakins. He also received instruction from the painter Louis Bail in New Haven, Connecticut. In 1864, Moore attended classes at the Mark Hopkins Institute in San Francisco, and until 1907, he would visit the “City by the Bay” regularly. In 1865, Moore went to Europe, spending time in Munich before traveling to Paris, where, in October 1866, he resumed his formal training in Gérôme’s atelier, drawing inspiration from his teacher’s emphasis on authentic detail and his taste for picturesque genre subjects. There, Moore worked alongside Eakins, who had mastered sign language in order to communicate with his friend. In March 1867, Moore enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, honing his drawing skills under the tutelage of Adolphe Yvon, among other leading French painters. In December 1869, Moore traveled around Spain with Eakins and the Philadelphia engraver, William Sartain. In 1870, he went to Madrid, where he met the Spanish painters Mariano Fortuny and Martin Rico y Ortega. When Eakins and Sartain returned to Paris, Moore remained in Spain, painting depictions of Moorish life in cities such as Segovia and Granada and fraternizing with upper-crust society. In 1872, he married Isabella de Cistue, the well-connected daughter of Colonel Cistue of Saragossa, who was related to the Queen of Spain. For the next two-and-a-half years, the couple lived in Morocco, where Moore painted portraits, interiors, and streetscapes, often accompanied by an armed guard (courtesy of the Grand Sharif) when painting outdoors. (For this aspect of Moore’s oeuvre, see Gerald M. Ackerman, American Orientalists [Courbevoie, France: ACR Édition, 1994], pp. 135–39.) In 1873, he went to Rome, spending two years studying with Fortuny, whose lively technique, bright palette, and penchant for small-format genre scenes made a lasting impression on him. By this point in his career, Moore had emerged as a “rapid workman” who could “finish a picture of given size and containing a given subject quicker than most painters whose style is more simple and less exacting” (New York Times, as quoted in Hajdel, p. 23). In 1874, Moore settled in New York City, maintaining a studio on East 14th Street, where he would remain until 1880. During these years, he participated intermittently in the annuals of the National Academy of Design in New York and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, exhibiting Moorish subjects and views of Spain. A well-known figure in Bay Area art circles, Moore had a one-man show at the Snow & May Gallery in San Francisco in 1877, and a solo exhibition at the Bohemian Club, also in San Francisco, in 1880. Indeed, Moore fraternized with many members of the city’s cultural elite, including Katherine Birdsall Johnson (1834–1893), a philanthropist and art collector who owned The Captive (current location unknown), one of his Orientalist subjects. (Johnson’s ownership of The Captive was reported in L. K., “A Popular Paris Artist,” New York Times, July 23, 1893.) According to one contemporary account, Johnson invited Moore and his wife to accompany her on a trip to Japan in 1880 and they readily accepted. (For Johnson’s connection to Moore’s visit to Japan, see Emma Willard and Her Pupils; or, Fifty Years of Troy Female Seminary [New York: Mrs. Russell Sage, 1898]. Johnson’s bond with the Moores was obviously strong, evidenced by the fact that she left them $25,000.00 in her will, which was published in the San Francisco Call on December 10, 1893.) That Moore would be receptive to making the arduous voyage across the Pacific is understandable in view of his penchant for foreign motifs. Having opened its doors to trade with the West in 1854, and in the wake of Japan’s presence at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, American artists were becoming increasingly fascinated by what one commentator referred to as that “ideal dreamland of the poet” (L. K., “A Popular Paris Artist”). Moore, who was in Japan during 1880–81, became one of the first American artists to travel to the “land of the rising sun,” preceded only by the illustrator, William Heime, who went there in 1851 in conjunction with the Japanese expedition of Commodore Matthew C. Perry; Edward Kern, a topographical artist and explorer who mapped the Japanese coast in 1855; and the Boston landscapist, Winckleworth Allan Gay, a resident of Japan from 1877 to 1880. More specifically, as William H. Gerdts has pointed out, Moore was the “first American painter to seriously address the appearance and mores of the Japanese people” (William H. Gerdts, American Artists in Japan, 1859–1925, exhib. cat. [New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries, 1996], p. 5). During his sojourn in Japan, Moore spent time in Tokyo, Yokohama, Kyoto, Nikko, and Osaka, carefully observing the local citizenry, their manners and mode of dress, and the country’s distinctive architecture. Working on easily portable panels, he created about sixty scenes of daily life, among them this sparkling portrayal of a young woman dressed in a traditional kimono and carrying a baby on her back, a paper parasol...Category

Late 19th Century Figurative Paintings

MaterialsOil, Wood Panel

- John F. Kennedy International AirportBy Marc TrujilloLocated in New York, NYEvery detail in Trujillo’s fast-paced, consumer-driven environments is the result of slow painting, of careful and keen observation, both analytic and synthetic. Trujillo depicts his...Category

2010s Contemporary Interior Paintings

MaterialsOil, Panel

- Tumbling into LightBy Angela FraleighLocated in New York, NYSigned and dated (on verso): Angela Fraleigh 2021Category

2010s Contemporary Figurative Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil, Panel

- Wait For Me ThereBy Angela FraleighLocated in New York, NYSigned and dated (on verso): Angela Fraleigh 2021Category

2010s Contemporary Figurative Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil, Panel

- Silent SparksBy Angela FraleighLocated in New York, NYSigned and dated (on verso): Angela Fraleigh 2021Category

2010s Contemporary Figurative Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil, Panel

- The Circle is Cast, We Are Between the WorldsBy Angela FraleighLocated in New York, NYIn Angela Fraleigh’s dynamic paintings, female subjects culled from art history become active protagonists in newly imagined spaces. In their original contexts, these figures were la...Category

2010s Figurative Paintings

MaterialsOil, Acrylic

You May Also Like

- Louis Cabié (1853-1939) - Landes à Pessac - GirondeBy Louis-Alexandre CabiéLocated in BELEYMAS, FRLouis-Alexandre CABIE (Dol-de-Bretagne 1853 - Bordeaux 1939) Landes in Pessac - Gironde Oil on panel H. 31 cm; L. 55 cm Signed lower right Louis Cabié, re...Category

1880s French School Landscape Paintings

MaterialsOil, Wood Panel

- Before the Beginning: figurative, oil, graphite on canvas over board, 2008Located in Petaluma, CABefore the Beginning is a figurative work and has a highly textured surface. It is canvas over board. The sides are unframed and are covered by linen tape. The black area around th...Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Figurative Paintings

MaterialsOil Crayon, Cotton Canvas, Oil, Wood Panel, Color Pencil, Graphite

- Barend Graat (1628-1709) Diana the huntress and her dogsLocated in BELEYMAS, FRBarend GRAAT (Amsterdam 1628 – Amsterdam 1709) Diana the Huntress Oil on wood H. 33.5 cm; L. 44 cm Signed lower right on the stone A discreet painter with respect to history, Barend...Category

1650s Dutch School Figurative Paintings

MaterialsWood Panel, Oil

- Young fisher - Phlegmatism allegoryLocated in BELEYMAS, FRAttributed to Godfried SCHALKEN (Made 1643 – The Hague 1706) Young fischer Oil on panel in one board H. 32.5 cm; L. 25.5 cm Around 1670/75 Related works: - Autograph version with numerous variants, Berlin, Gemaldegalerie, Inv. N°837 - Copy or workshop version of our painting with slight variations but of inferior quality, Germany, sold at Berlinghof Auktionshaus in 2002 The object of this notice is not to produce a biography of Schalken, the reference work by Thierry Beherman published by Maeght in 1988. The goal here is to understand this version of a painting of formidable craftsmanship and to compare it to the work preserved in Berlin with its many variants in order to draw some hypotheses for conclusions Our young angler is a very interesting subject that can be found as early as the 16th century to invoke one of the four temperaments. Not melancholy as one might think at first glance, but phlegmatic character. The interpretation of astrological symbols closely linked peach and phlegm, laziness, slowness, often represented alongside the moon. Here the composition is very clear in this sense. The young man, chin resting on his arm, looks at his modest cane, the cork of which he soaks alongside snails and butterflies located in the Irises. All near a willow under a heavy sky, like a night sky. All the elements are there to give an explanation of the subject and not to leave the spectator in front of a simple genre scene. Let's go back to the willow, a tree that loses its fruits before they mature. It is often considered a symbol of lost youth, a reference to passivity or times of debauchery. Plato advised in his time to banish fishing from the education of children since it is an activity of expectation and not of exercise or reflection. Needless to explain the presence of small slow-moving animals with short lives or flowers… The image speaks for itself! Let's go back to the differences between the Berlin version and ours, of which it must be recognized that the quality is slightly lower and therefore can hardly be given with certainty to Schalken itself. This version has some additional elements compared to ours. In our version, the row of willows cut into trunks located to the left of the composition is replaced by a simple area of reeds that opens up to a luminous sky. The sky is also different by the clouds represented. A white butterfly flying in the middle of the Irises has been removed, as has a large leaf located on the back of the young fisherman at the foot of the willow. Only addition to our table in addition to the Berlin version: a second fish near the earthen pot...Category

1680s Flemish School Figurative Paintings

MaterialsWood Panel, Oil

- 17th Century By Paulus Bor Heraclitus and Democritus Oil on PanelLocated in Milano, Lombardia"Cassetta" frame in ebonized wood. Publications: - Expertise by Prof. Gianni Papi; - G. Papi, Un misto di grano e di pula. Scritti su Caravaggio e l’ambiente caravaggesco, Roma 2...Category

17th Century Old Masters Figurative Paintings

MaterialsOil, Wood Panel

- Beautiful cubist style oil painting "A Day in the Sun" by ImpigliaBy Giancarlo ImpigliaLocated in Bridgehampton, NYA recent, large work by the masterful Giancarlo Impiglia, whose value has been steadily increasing. Born in Rome, Impiglia moved to New York in the 70s, where he established a signa...Category

2010s Figurative Paintings

MaterialsWood Panel, Oil

Recently Viewed

View AllMore Ways To Browse

All Japanese Art

Japanese Beauties

Japanese American Artist

Children Size

Children In The Woods

Used Tortoise

Japanese Photographs

No Children

Japanese War

Japan War

Photograph Children

Children Photograph

Antique Japanese Painting

Antique Japanese Paintings

Japanese Women

Japan Street

Japanese Market

Japanned English