Items Similar to Still Life with Squash, Gourds, Stoneware, and a Basket with Fruit and Cheese

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 5

Still Life with Squash, Gourds, Stoneware, and a Basket with Fruit and Cheese

About the Item

Provenance:

Selma Herringman, New York, ca. 1955-2013; thence by descent to:

Private Collection, New York, 2013-2020

This seventeenth century Spanish still-life of a laden table, known as a bodegón, stands out for its dramatic lighting and for the detailed description of each object. The artist’s confident use of chiaroscuro enables the sliced-open squash in the left foreground to appear as if emerging out of the darkness and projecting towards the viewer. The light source emanates from the upper left, illuminating the array, and its strength is made apparent by the reflections on the pitcher, pot, and the fruit in the basket. Visible brush strokes accentuate the vegetables’ rough surfaces and delicate interiors. Although the painter of this striking work remains unknown, it is a characteristic example of the pioneering Spanish still-lifes of the baroque period, which brought inanimate objects alive on canvas.

In our painting, the knife and the large yellow squash boldly protrude off the table. Balancing objects on the edge of a table was a clever way for still-life painters to emphasize the three-dimensionality of the objects depicted, as well a way to lend a sense of drama to an otherwise static image. The knife here teeters on the edge, appearing as if it might fall off the table and out of the painting at any moment. The shape and consistency of the squash at left is brilliantly conveyed through the light brush strokes that define the vegetable’s fleshy and feathery interior. The smaller gourds—gathered together in a pile—are shrouded partly in darkness and stand out for their rugged, bumpy exterior. The stoneware has a brassy glaze, and the earthy tones of the vessels are carefully modulated by their interaction with the light and shadow that falls across them. The artist has cleverly arranged the still-life in a V-shaped composition, with a triangular slice of cheese standing upright, serving as its pinnacle.

Independent still-lifes only became an important pictorial genre in the first years of the seventeenth century. In Italy, and particularly through the revolutionary works of Caravaggio, painted objects became carriers of meaning, and their depiction and arrangement the province of serious artistic scrutiny. Caravaggio famously asserted that it was equally difficult to paint a still-life as it was to paint figures, and the elevation of this new art form would have profound consequences to the present day. In Spain Juan Sanchez Cotan, almost an exact contemporary of Caravaggio, inaugurated the distinctive tradition of Spanish still-life painting with memorable images of common vegetables and fruits depicted with reverence and elegance. His Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber (Fig. 1) both illustrates the origins of this tradition and provides a useful comparison to the present work. The objects—conventionally thought of as unremarkable, if not ugly—are depicted in painstaking detail against a dark background. They are arranged in a parabolic composition, with the quince and leafy cabbage suspended in the air on strings, while the slice of freshly cut melon and the cucumber jut out beyond the ledge. The varied shapes and textures so meticulously recorded contrast with the harsh geometrical surround of the window and the uniform black background, giving these objects a new-found importance and beauty.

The author of our painting is not known. Although there are compositional echoes of the works of such artists as Blas de Ledesma and Alejandro de Loarte, the style of our painting is not sufficiently distinctive to permit its association with any known painter. But it is clearly a work of the period, one characterized by what seems a charming naiveté in its frank and objective representation of the objects depicted.

In our painting the anonymous artist has chosen especially humble subjects. The gourds are common, and the ceramic pitcher and crock unadorned and utilitarian. The basket, fruit, and cheese are those of the laborer, not the prince. These are not the luxury possessions one will find in Dutch still-lifes later in the century, included to reflect the wealth and sophistication of their owners. Rather here, with the depiction of modest objects on a bare table, the artist extols both the significance and beauty of the everyday, as he subtly celebrates the humility of their owner.

- Dimensions:Height: 20.5 in (52.07 cm)Width: 24.5 in (62.23 cm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Circle Of:Juan Sanchez Cotan (1560 - 1627, Spanish)

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:New York, NY

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU1027909252

About the Seller

5.0

Recognized Seller

These prestigious sellers are industry leaders and represent the highest echelon for item quality and design.

Established in 1997

1stDibs seller since 2012

17 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 11 hours

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Ships From: New York, NY

- Return PolicyThis item cannot be returned.

More From This SellerView All

- Julius Caesar on HorsebackBy Antonio TempestaLocated in New York, NYProvenance: Private Collection, South America Antonio Tempesta began his career in Florence, working on the decoration of the Palazzo Vecchio under the direction of Giorgio Vasari. He was a pupil first of Santi di Tito...Category

16th Century Old Masters Paintings

MaterialsOil, Canvas

- Portrait of a Lady with a ChiqueadorLocated in New York, NYProvenance: Torres Family Collection, Asunción, Paraguay, ca. 1967-2017 While the genre of portraiture flourished in the New World, very few examples of early Spanish colonial portraits have survived to the present day. This remarkable painting is a rare example of female portraiture, depicting a member of the highest echelons of society in Cuzco during the last quarter of the 17th century. Its most distinctive feature is the false beauty mark (called a chiqueador) that the sitter wears on her left temple. Chiqueadores served both a cosmetic and medicinal function. In addition to beautifying their wearers, these silk or velvet pouches often contained medicinal herbs thought to cure headaches. This painting depicts an unidentified lady from the Creole elite in Cuzco. Her formal posture and black costume are both typical of the established conventions of period portraiture and in line with the severe fashion of the Spanish court under the reign of Charles II, which remained current until the 18th century. She is shown in three-quarter profile, her long braids tied with soft pink bows and decorated with quatrefoil flowers, likely made of silver. Her facial features are idealized and rendered with great subtly, particularly in the rosy cheeks. While this portrait lacks the conventional coat of arms or cartouche that identifies the sitter, her high status is made clear by the wealth of jewels and luxury materials present in the painting. She is placed in an interior, set off against the red velvet curtain tied in the middle with a knot on her right, and the table covered with gold-trimmed red velvet cloth at the left. The sitter wears a four-tier pearl necklace with a knot in the center with matching three-tiered pearl bracelets and a cross-shaped earing with three increasingly large pearls. She also has several gold and silver rings on both hands—one holds a pair of silver gloves with red lining and the other is posed on a golden metal box, possibly a jewelry box. The materials of her costume are also of the highest quality, particularly the white lace trim of her wide neckline and circular cuffs. The historical moment in which this painting was produced was particularly rich in commissions of this kind. Following his arrival in Cuzco from Spain in the early 1670’s, bishop Manuel de Mollinedo y Angulo actively promoted the emergence of a distinctive regional school of painting in the city. Additionally, with the increase of wealth and economic prosperity in the New World, portraits quickly became a way for the growing elite class to celebrate their place in society and to preserve their memory. Portraits like this one would have been prominently displayed in a family’s home, perhaps in a dynastic portrait gallery. We are grateful to Professor Luis Eduardo Wuffarden for his assistance cataloguing this painting on the basis of high-resolution images. He has written that “the sober palette of the canvas, the quality of the pigments, the degree of aging, and the craquelure pattern on the painting layer confirm it to be an authentic and representative work of the Cuzco school of painting...Category

17th Century Old Masters Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil

- A WolfLocated in New York, NYProvenance: The Marchesi Strozzi, Palazzo Strozzi, Florence Sale, Christie’s, London, May 20, 1993, lot 315, as by Carl Borromaus Andreas Ruthart...Category

17th Century Old Masters Animal Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Paper, Oil

- An Architectural Capriccio with the Preaching of an ApostleBy Giovanni Paolo PaniniLocated in New York, NYProvenance: Santambrogio Antichità, Milan; sold, 2007 to: Filippo Pernisa, Milan; by whom sold, 2010, to: Private Collection, Melide, Switzerland De Primi Fine Art, Lugano, Switzerland; from whom acquired, 2011 by: Private Collection, Connecticut (2011-present) Literature: Ferdinando Arisi, “Ancora sui dipinti giovanili del Panini,” Strenna Piacentina (Piacenza, 2009): pp. 48, 57, 65, fig. 31, as by Panini Ferdinando Arisi, “Panini o Ghisolfi o Carlieri? A proposito dei dipinti giovanili,” Strenna Piacentina, (Piacenza, 2010), pp. 100, 105, 116, fig. 101, as an early work by Panini, a variant of Panini’s painting in the Museo Cristiano, Esztergom, Hungary. This architectural capriccio is one of the earliest paintings by Giovanni Paolo Panini, the preeminent painter of vedute and capricci in 18th-century Rome. The attribution to Panini has been endorsed by Ferdinando Arisi, and a recent cleaning of the painting revealed the artist’s signature in the lower right. Like many of his fellow painters working in Rome during his day, Panini was not a native of the Eternal City. He first trained as a painter and stage designer in his hometown of Piacenza and moved to Rome at the age of 20 in November 1711 to study figure painting. Panini joined the workshop of Benedetto Luti (1666-1724) and from 1712 was living on the Piazza Farnese. Panini, like many before and after him, was spellbound by Rome and its classical past. He remained in the city for the rest of his career, specializing in depicting Rome’s most important monuments, as well as creating picturesque scenes like this one that evoked the city’s ancient splendor. The 18th century art historian Lione Pascoli, who likely knew Panini personally, records in his 1730 biography of the artist that when Panini came to Rome, he was already “an excellent master and a distinguished painter of perspective, landscape, and architecture.” Panini’s earliest works from this period still show the evidence of his artistic formation in Piacenza, especially the influence of the view painter Giovanni Ghisolfi (1623-1683). However, they were also clearly shaped by his contact in Rome with the architectural capricci of Alberto Carlieri...Category

18th Century Old Masters Figurative Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil

- View of St. John’s Cathedral, AntiguaLocated in New York, NYProvenance: Robert Hollberton, Antigua, ca. 1841 Private Collection, New York The present painting depicts Old St. John’s Cathedral on the island of Antigua. The church was erected in the 1720s on the designs of the architect Robert Cullen. It measured 130 feet by 50 feet with north and south porches 23 x 20 ½ feet. The tower, 50 feet high with its cupola, was added in 1789. The church was elevated to the status of a cathedral, but disaster struck in the form of an earthquake that destroyed the building on 8 February 1843. A memorandum of that date relates the event: “On Wednesday, 8th February, 1843, this island was visited by a most terrific and destructive earthquake. At twenty minutes before eleven o’clock in the forenoon, while the bell was ringing for prayers, and the venerable Robert Holberton was in the vestry-room, awaiting the arrival of persons to have their marriage solemnized, before the commencement of the morning service, the whole edifice, from one end to the other, was suddenly and violently agitated. Every one within the church, after the first shock, was compelled to escape for his life. The tower was rent from the top to the bottom; the north dial of the clock precipitated to the ground with a dreadful crash; the east parapet wall of the tower thrown upon the roof of the church; almost the whole of the north-west wall by the north gallery fell out in a mass; the north-east wall was protruded beyond the perpendicular; the altar-piece, the public monument erected to the memory of lord Lavington, and the private monuments, hearing the names of Kelsick, Warner, Otley, and Atkinson, fell down piecemeal inside; a large portion of the top of the east wall fell, and the whole of the south-east wall was precipitated into the churchyard, carrying along with it two of the cast-iron windows, while the other six remained projecting from the walls in which they had been originally inserted; a large pile of heavy cut stones and masses of brick fell down at the south and at the north doors; seven of the large frontpipes of the organ were thrown out by the violence of the shock, and many of the metal and wooden pipes within displaced; the massive basin of the font was tossed from the pedestal on which it rested, and pitched upon the pavement beneath uninjured. Thus, within the space of three minutes, this church was reduced to a pile of crumbling ruins; the walls that were left standing being rent in every part, the main roof only remaining sound, being supported by the hard wood pillars.” The entrance from the southern side into the cathedral, which was erected in 1789, included two imposing statues, one of Saint John the Divine and the other of Saint John the Baptist in flowing robes. It is said that these statues were confiscated by the British Navy from the French ship HMS Temple in Martinique waters in 1756 during the Seven Years’ War and moved to the church. The statues are still in situ and can be seen today, much as they appeared in Bisbee’s painting, but with the new cathedral in the background (Fig. 1). Little is known of the career of Ezra Bisbee. He was born in Sag Harbor, New York in 1808 and appears to have had a career as a political cartoonist and a printmaker. His handsome Portrait of President Andrew Jackson is dated 1833, and several political lithographs...Category

19th Century Old Masters Landscape Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil

- Head of an AngelLocated in New York, NYProcaccini was born in Bologna, but his family moved to Milan when the artist was eleven years old. His artistic education was evidently familial— from his father Ercole and his elder brothers Camillo and Carlo Antonio, all painters—but his career began as a sculptor, and at an early age: his first known commission, a sculpted saint for the Duomo of Milan, came when he was only seventeen years old. Procaccini’s earliest documented painting, the Pietà for the Church of Santa Maria presso San Celso in Milan, was completed by 1604. By this time the artist had made the trip to Parma recorded by his biographers, where he studied Correggio, Mazzola Bedoli, and especially Parmigianino; reflections of their work are apparent throughout Procaccini's career. As Dr. Hugh Brigstocke has recently indicated, the present oil sketch is preparatory for the figure of the angel seen between the heads of the Virgin and St. Charles Borrommeo in Procaccini's altarpiece in the Church of Santa Afra in Brescia (ill. in Il Seicento Lombardo; Catalogo dei dipinti e delle sculture, exh. cat. Milan 1973, no. 98, pl. 113). As such it is the only known oil sketch of Procaccini's that can be directly connected with an extant altarpiece. The finished canvas, The Virgin and Child with Saints Charles Borrommeo and Latino with Angels, remains in the church for which it was painted; it is one of the most significant works of Procaccini's maturity and is generally dated after the artist's trip to Genoa in 1618. The Head of an Angel is an immediate study, no doubt taken from life, but one stylistically suffused with strong echoes of Correggio and Leonardo. Luigi Lanzi, writing of the completed altarpiece in 1796, specifically commented on Procaccini's indebtedness to Correggio (as well as the expressions of the angels) here: “Di Giulio Cesare...Category

17th Century Old Masters Figurative Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Paper, Oil

You May Also Like

- Baroque silver Vase with Flowers with a Fruit Tray and a Clock by A. ZuccatiLocated in PARIS, FRThis unpublished composition is a recent addition to Adeodato Zuccati’s catalog. The study of this painting by Gianluca Bocchi, an Italian art historian specializing in Italian still lives, is available upon request. This composition is typical of the productions of Adeodato Zuccati, an Emilian painter...Category

Late 17th Century Old Masters Still-life Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil

- Still Life with Apples and Nuts, 17th Century, Old Master, Spanish PaintingLocated in Greven, DEJuan Sánchez Cotán (1560 - 1627) was one of the most important still life painters in Spain and beyond. He developed a certain type of still life with a ...Category

17th Century Old Masters Still-life Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil

- 17th Century by Giovanni Paolo Castelli Still Life Oil on CanvasBy Giovanni Paolo Castelli detto SpadinoLocated in Milano, LombardiaGiovanni Paolo Castelli called Spadino (Rome 1659 - Rome 1730) Still life Oil on canvas, cm. 81x31 - with frame cm. 92x41 Shaped and gilded wo...Category

Late 17th Century Old Masters Still-life Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Cotton Canvas, Oil

- 17th Century By Lombard Artist Still Life with Birds and Burning Fuse Oil/canvasLocated in Milano, Lombardia"Cassetta" frame in sculpted, carved, gilded wood. Expertise by Gianluca Bocchi.Category

17th Century Old Masters Still-life Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil

- Florals in classic urn Old Masters 17th century Dutch styleLocated in Hillsborough, NCFloral with Urn is in a classical Dutch style that dates to the 17th century. The bright flowers drape the urn in whites, crimsons and pinks, standing out against the darker foliage...Category

17th Century Old Masters Still-life Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil

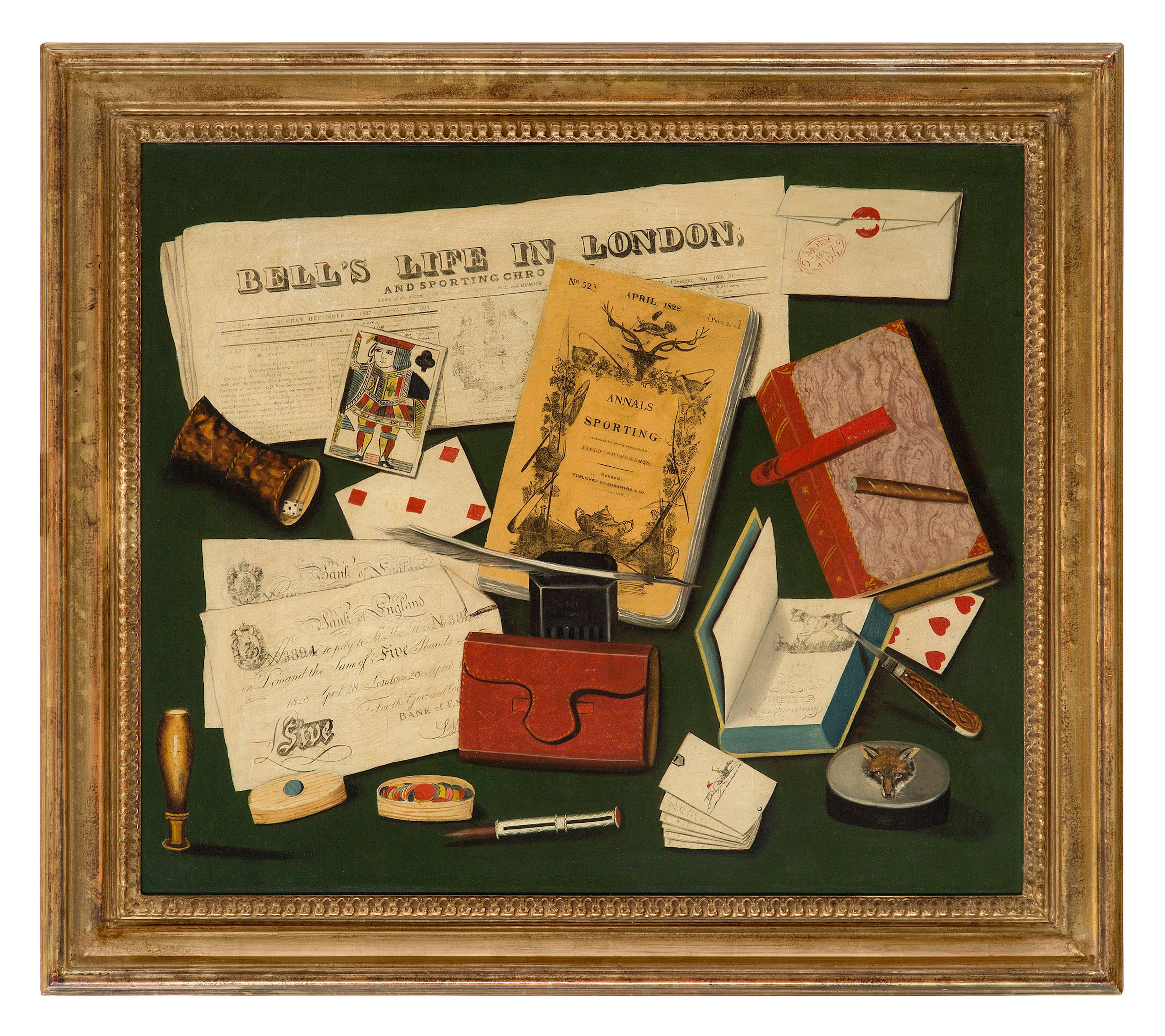

- A gentleman’s vicesLocated in London, GBEnglish School, circa 1827 A gentleman’s vices the newspaper dated ‘Sunday December 23 1827’ (upper left) oil on canvas 20 ¾ x 24 ½ in. (52.7 x 62.3 cm.) frame 25 ⅝ x 29 ¼ in. (65.1...Category

Early 19th Century Old Masters Still-life Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Oil

Recently Viewed

View AllMore Ways To Browse

Antique Table Knife

Antique Exterior Lighting

Brush Pot Stand

Knife Edge Table

Spanish Exterior Light

Antique Brush Pot

Spanish Canvas 17th

Art Bla Bla Bla

Fruit Basket Light

Crock Antique

Antique Crock

Antique Crocks

Crocks Antique

Antique Crocks Crocks

Ceramic Fruit Italy

Antique Knife Collection

Glazed Oil Pot

Ceramic Fruit Table