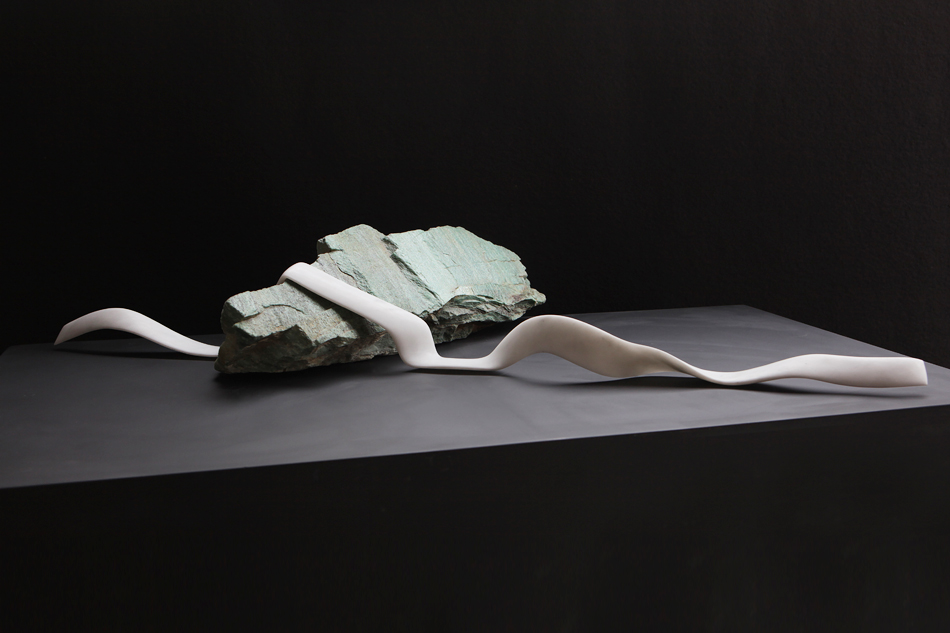

September 14, 2015Portrait of Elizabeth Turk by Samuel C. Frost. Top: Marble & Baja Beach Stone 12, 2015 (detail), is among Turk’s sculptures that blend highly carved marble and more natural forms in the new show “Tensions” at Hirschl & Adler Modern in New York. Courtesy of the artist and Hirschl & Adler Modern, New York. © Eric Stoner

Elizabeth Turk stands in the yard of Chiarini Marble & Stone as a forklift moves massive slabs of rock nearby and several workers grind away at sculptures, their tools filling the morning air with the sounds of a high-volume dental office. Turk, her bright eyes particularly blue in the warm California sunlight, is taking an account of everything that was stolen.

The night before, thieves had hopped the fence of the marble yard and made their way to Turk’s studio area, cutting the latches off metal lockers and stealing a bunch of old tools. Turk had added the locks after a similar break-in last year, but the burglars brought bolt cutters this time. What they didn’t bring was a guide to contemporary art. Otherwise, they probably would’ve nabbed the finely carved sculptures on the very next shelf, those created by Turk, the recipient of a MacArthur “genius grant” Fellowship.

When Turk first set up shop in the yard, 13 years ago, the Pasadena native worked outdoors under the sun, then she upgraded to a tent, and now she’s spread out across the compound, dodging her landlord’s forklifts as they ferry marble to be fitted in homes all along Newport Beach. Located just off the Santa Ana Freeway between La Chiquita Grocery and an auto-dismantling shop, Chiarini Marble was Turk’s refuge from the hectic New York art world, a not-very-quiet place to craft her delicate stone sculptures. “I’m like a parasite,” the artist says, showing off the crannies she has found within the grounds to create works that make marble seem as light as silk.

She is perhaps best known for her “Cages:” intricate works sliced from quarter-ton blocks of marble that flow like one long Möbius strip. Michelangelo claimed he saw figures in marble and carved away until he set them free, but for Turk the process is more of a conversation. She’s constantly editing, grinding, seeing how far she can take one curve, extend one line, turn marble into lace. If she goes too far — crack — the piece is kaput.

A Turk sculpture amid classical-style reliefs at Chiarini Marble & Stone in Santa Ana, California, where her studio is located. Photo by Samuel C. Frost

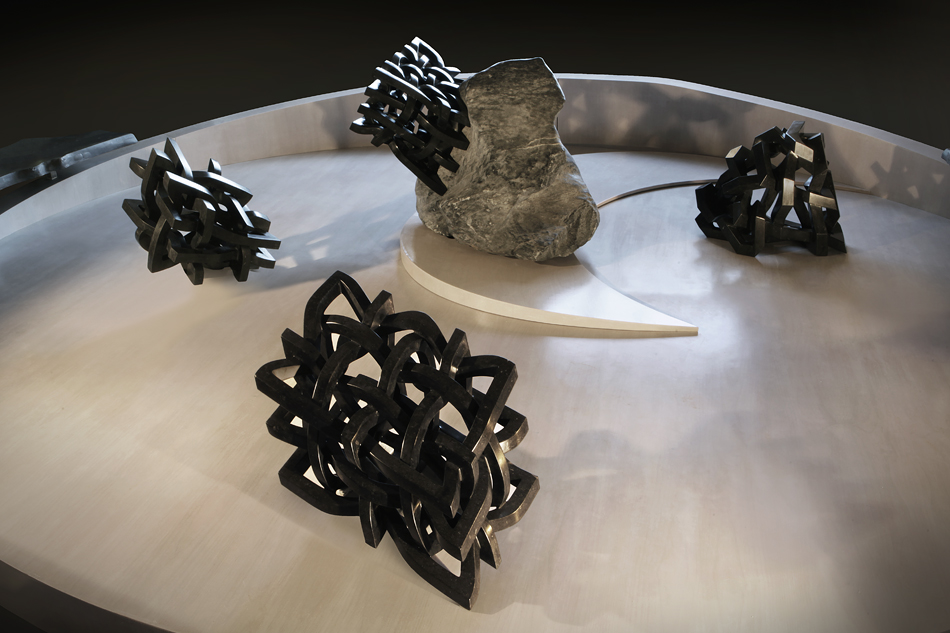

When I met up with Turk, she was finishing the sculptures and videos that will appear in her show “Tensions,” at Hirschl & Adler Modern in New York from September 17 through October 24. These latest works blend sculpted marble with natural rocks and wood in a way that’s both harmonious and, well, tense. “All the pieces in the show are about the tension between the beauty of nature and that crazy human desire to control everything,” she says. “So you’ll have something that’s naturally carved and something that’s just insanely over carved.” You can see this juxtaposition in her new series “Marble and Baja Beach Stone,” with each piece featuring a big gray beach rock that’s been sliced in half and used as a bookend for intricately intertwined swirls of white marble.

The marble yard has computers and a big 3-D milling machine that can carve stone into almost any shape. If you want a marble bowling ball, the miller can make one lickety-split. “It’s like a 3-D Xerox machine,” Turk says. “In a lot of ways, that’s why I started pushing my works to be about the undercuts and the emptiness. It’s sort of a combination of trying to use the new technology — the grinding and the diamond tools — and then bringing in a little bit of the old hand work. I use the machine as a tool to get to a certain point and then try to push the sculpture further by hand.”

Turk’s output moves across various media, but she says she’s aware that — just like Jackson Pollock is known for his splatters and William Wegman for his Weimaraners — she is “the marble lady.” This label might be reductive, but within it is the acknowledgment that she has led a one-woman Renaissance of marble as a medium. And her mastery of classical form and technique, combined with her use of 3-D milling, places her at the leading edge of a tradition dominated by men.

When the artist first set up shop at Chiarini Marble, she worked outdoors, then she got a tent, and now she’s spread out in locations across the compound, including this enclosed studio. Photo by Samuel C. Frost

“That’s all I think about with my work: ‘If I cut it here, will it still hold up? Or will it just go snap?’”

Back in the air-conditioned confines of her office space, Turk plays with the arrangement of some rocks, roughing up the shiny piece of metal on which she will attach her formations with magnets. She says she met short-story writer and fellow MacArthur “genius” George Saunders shortly after receiving her award in 2010, and they powwowed about process. “He kept talking about all the years he spent — at his lunch break, after work, an hour here, forty-five minutes there — just editing the paragraph he wrote the night before, trying to get it tighter and tighter, and I love that,” she says. “That’s all I was thinking about with my work: ‘If I cut it here, will it still hold up? Will that line still work? … Or will it just go snap?’”

Being called a genius put Turk under a lot pressure, but that was several shows and rave reviews ago. Her 2012 exhibition at Hirschl & Adler featured a series of undulating “Cages” that took years to create and appeared in the pages of ARTnews, Art+Auction and Elle Decor. Another milestone occurred last year, when the Laguna Art Museum mounted a mini retrospective of her work in the county where she grew up.

Turk’s post-MacArthur creative path has not been linear, but it never was. She majored in international relations at Scripps College and even worked for a while in Washington, D.C., before chucking it all to become an artist, getting her MFA in sculpture from the Maryland Institute College of Art. The plan was to try it for a year. Maybe longer. “I’ve been working like a crazy person, but for me it was the only choice,” she says. “I guess I could be a dentist. I have all the right tools. Except people’s teeth would come out weird. I’d have to be the dentist next to the tattoo parlor.”

Turk with the 3-D milling machine that carves marble blocks into intricate sculptures before she takes the forms further by hand. Photo by Samuel C. Frost