February 3, 2019Trained as an architect, Florence Knoll Bassett — seen here defined good taste in the middle of the last century. T

We’re like art dealers,” Florence Knoll Bassett once told the writer Peter Blake. “We want fresh, original work. And we want it from anybody who can produce it.”

Knoll Bassett, who died on January 25th at 101, was speaking of the period during and immediately after World War II, when she and her first husband, Hans Knoll, were turning his small furniture company into a modernist powerhouse. The pieces Knoll released during those years — including Harry Bertoia’s gridded Diamond chair (1952), Eero Saarinen’s upholstered Womb chair (1948) and Isamu Noguchi’s thrilling Cyclone table (1954–57) — have become classics.

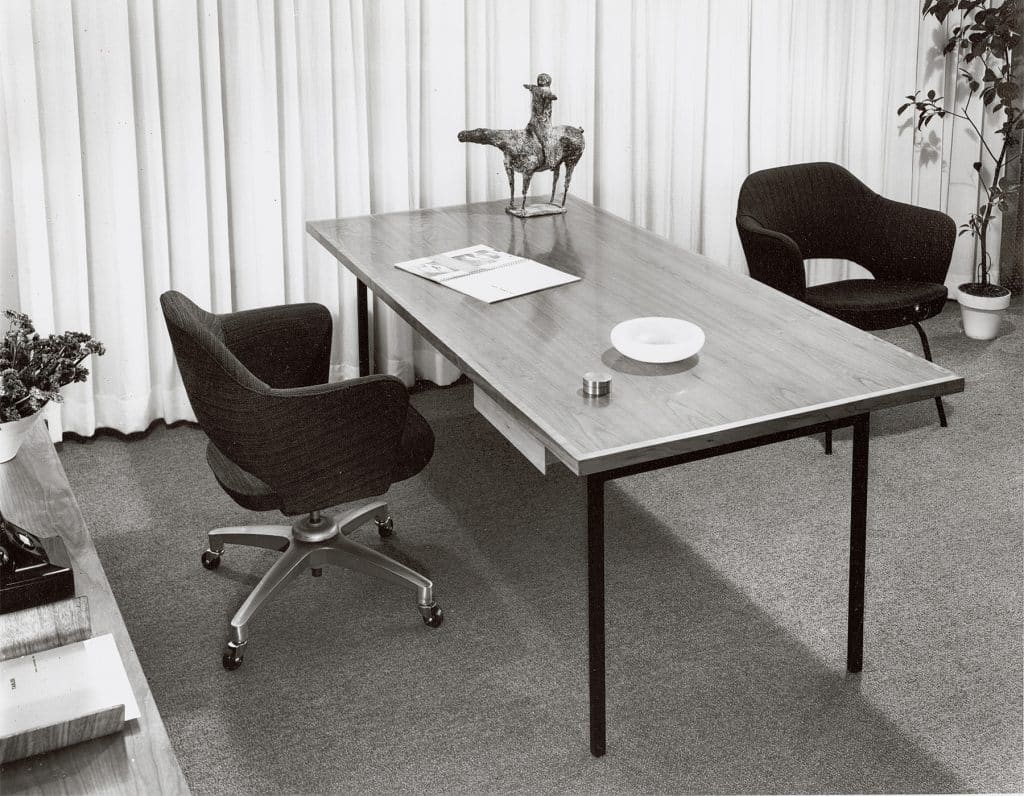

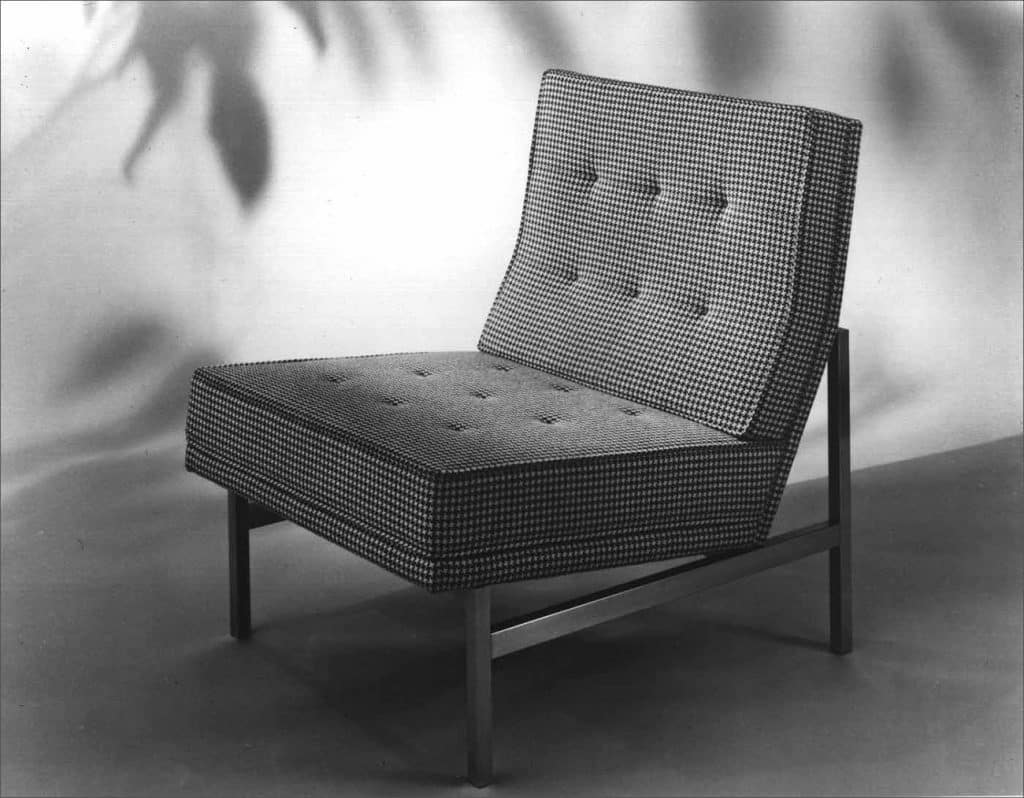

Knoll Bassett’s own designs were equally important. Trained as an architect, she was determined to remake the American office. For that, according to Paul Makovsky — a journalist who is working on a biography of Knoll Bassett (and was her friend for 20 years) — she needed to create “fill-in” pieces that worked alongside the more sculptural items. To accompany the Womb chair, for example, she designed a far more sober line of sofas and chairs. But her fill-ins became icons themselves.

Evan Lobel, of mid-century dealer Lobel Modern, Inc., says he has sold 30 or 40 Florence Knoll pieces over the years and describes them as “crisp, clean, classic modernism. They’re impeccably well-made, and they go with almost anything.”

Knoll Bassett helped promote and distribute such icons of modern design as the Tulip table, designed by her childhood friend Eero Saarinen, which is seen here in a San Francisco office and study by Nicole Hollis. Photo by Laure Joliet

And, of course, the Florence Knoll pieces, designed primarily for commercial interiors, long ago became choice items in houses and apartments. Knoll Bassett “remains incredibly important to the field of architecture and design,” says the Brooklyn-based interior designer Elizabeth Roberts, “and not only because she was a pioneering woman in a field that continues to be dominated by men but also because her work remains fresh and relevant as it continues to influence designers today.”

That would please Knoll Bassett, who wanted her pieces to be practical. In 1983, the New York Times quoted her as saying, “Have you ever sat in a Michael Graves chair? There’s no thought about pitch and comfort and little relationship to industrial production — it’s really arts-and-crafts design.” At Knoll, by contrast, she stated, “[w]e worked months, sometimes years, on the comfort of a chair.

“Yes, it was an exciting time,” she continued. “But it was mostly hard work. We had to battle the prejudice against contemporary design.”

Born Florence Schust (and known by the nickname Shu) in Saginaw, Michigan, she was orphaned at age 12. She enrolled in a girls’ boarding school that was part of the Cranbrook Academy of Art, then run by Eliel Saarinen. She was practically adopted by Saarinen and his wife, Loja, and befriended by their son Eero. She went on to study with Mies van der Rohe, and to work for Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and the firm Harrison and Abramovitz, all before meeting Hans Knoll in 1943. She liked him — but not the furniture he was making. “Many of the designs that he had at that time were ones that I did not approve of,” she told interviewers for an oral history of Knoll. “I felt they were too romantic and didn’t quite fit in with my ideas. That’s how the thing started.”

Soon, she was looking for designers who shared her sensibility. As Blake observed in Architectural Forum, she and Hans “worked like maniacs, day and night, trying to find ways of designing and manufacturing this or that, squeezing materials out of the war economy, discovering and then supporting young and relatively unknown designers.”

Timothy Godbold deployed a quartet of Knoll Bassett’s marble-and-steel coffee tables in a family home in New York’s Bridgehampton. Photo by Alec Hemer

One of her first calls was to Eero Saarinen, whom she once described as “like a brother.” She famously asked him to come up with “a chair that was like a basket full of pillows.” She also wanted a seat she could move around in. “I was sick and tired of these chairs that held you in one position,” she said. The result, labeled the Womb chair, was an early experiment with fiberglass and proved tricky to produce — until she found a ship builder in New Jersey who was willing to take it on.

Other collaborators included George Nakashima, Alexander Girard, Bertoia and Noguchi. Saarinen designed his pedestal collection, including the elegant Tulip chair, at her behest.

She wanted pieces that captured each architect’s sensibility in its purest form. In the 1950s, she put the Barcelona chair (designed in the 1920s by Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich) into production. As Makovsky explains, in the Barcelona chair, supported on stainless-steel bars hand-polished to a mirror finish, “she saw Mies being Mies, whereas with his other early chairs made of tubular steel, that was Mies on the way to being Mies.”

Hans Knoll died in a car accident in 1955; his wife remained at the company for another 10 years. Then, in 1965, when she was 48, she moved to Florida to live full-time with her second husband, banker Harry Hood Bassett (whom she’d married in 1958). She occasionally gave interviews, including several to Makovsky, who accompanied her to the White House when she was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 2003. Makovsky says that Knoll Bassett, who lived more than 50 years after leaving the company, “had a dry sense of humor.” Looking through auction catalogues featuring her work, she told him, “I’m an antique now.”