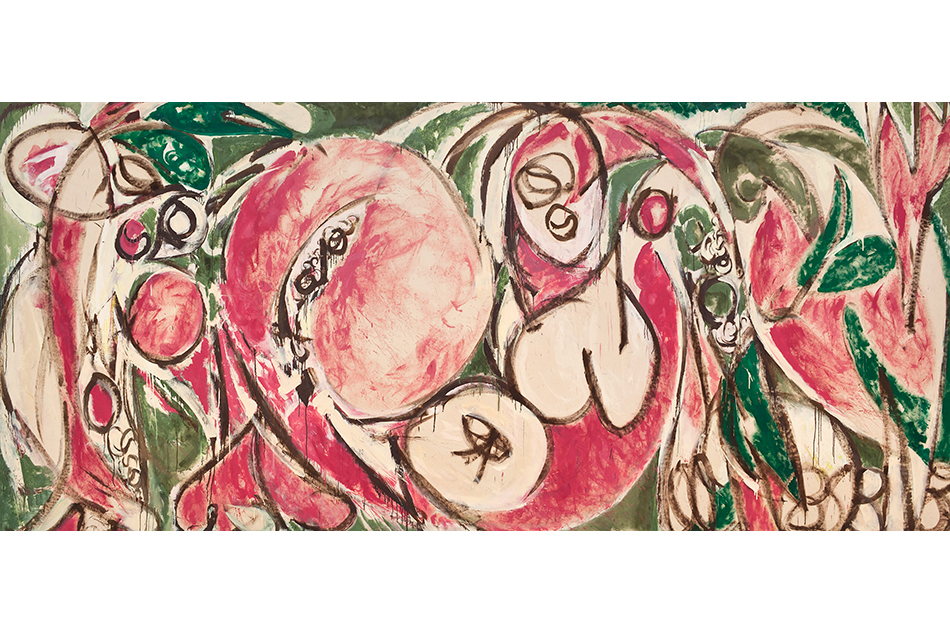

August 8, 2016Sonia Gechtoff felt welcomed by galleries in San Francisco, where she began her career in the early 1950s, but she says the New York art scene seemed closed off to women. Gechtoff is among the 12 oft-overlooked artists currently getting their due in the Denver Art Museum’s “Women of Abstract Expressionism” (photo courtesy of Sonia Gechtoff). Top: Antigone I, 1958, by Ethel Schwabacher. © Estate of Ethel Schwabacher

In the 1950s, artist Sonia Gechtoff had a breakthrough moment at an exhibition that included paintings by Clyfford Still. Encountering Still’s Abstract Expressionist technique flipped a switch inside her. “I was so excited that it took me awhile to get it straightened out in my head,” recalls the 89-year-old New Yorker, who up until that point had been a realist painter. “There was so much freedom and openness. It was thrilling that you could discover something personal directly on the canvas, without adhering to a recognizable subject.” Gechtoff adopted the gestural style, and over the past six decades, her work has been exhibited internationally and acquired by major collections.

Yet she and other women of the AbEx movement aren’t household names like their male counterparts Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, although many of them were equally involved in the art world of the time. The Denver Art Museum’s exhibition “Women of Abstract Expressionism,” on view until September 25, seeks to bring these female artists out of the shadows once and for all.

“Historically, this movement has always been about the paint-splattered man,” declares Gwen Chanzit, DAM’s curator of modern art. “In museums and textbooks, the story has been limited, and so many big, first-rate paintings have been left out.” A number of AbEx women earned critical acclaim when they were active and had their work featured in high-profile exhibitions, such as the famed 1951 Ninth Street Show. They experimented vigorously, developed their own styles and produced significant bodies of work. But the recognition they received still paled beside that accorded their male peers. Sexism is one reason these women were overlooked, but family and household responsibilities also led to inconsistent careers, and societal pressure even drove some to destroy their canvases.

Hudson River Day Line, 1955, by Joan Mitchell. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

The exhibition focuses on 12 key women artists, displaying multiple works by each. In addition to Gechtoff, they include Mary Abbott, Jay DeFeo, Perle Fine, Helen Frankenthaler, Judith Godwin, Grace Hartigan, Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Deborah Remington and Ethel Schwabacher. Only a handful of them — notably, Frankenthaler and Mitchell — are widely known.

Abstract Expressionist painting was characterized by direct, exuberant gestures — strikingly rich, textural brushstrokes that took advantage of every inch of the canvases, which were generally large. The movement, which was influenced by the fluidity of European Surrealism, gave birth to a uniquely American art form that was influential around the world.

“Unlike, say, a Cubist painting, you cannot teach someone how to make a painting like this,” Chanzit says. “These paintings are deeply personal responses to things that moved these individuals — an event, a place, literature, poetry and the like.”

All Green, 1954, by Mary Abbott. © Mary Abbott

De Kooning’s Bullfight (1959) grew out of her experience of that violent Spanish tradition, while Krasner’s The Seasons (1957) is clearly a celebration of the botanical world. Although the women adhered to the same artistic principles, each one’s style was distinct. Gechtoff’s The Beginning (1960), which was inspired by angels depicted in an Italian fresco, includes many colors applied with a profusion of smallish brushstrokes, while in Godwin’s Martha Graham — Lamentation (1956), the brushstrokes evoke the bold choreography of Graham, her friend, to whom the work is a tribute.

Within a movement that, as Chanzit observes in the exhibition catalogue, was defined by the “heroic machismo spirit,” the women’s approach was perhaps more personal than that of their male counterparts. Many of the women were painting in response to nature, she writes, in contrast to Pollock, who famously declared, “I am nature.” Strikingly few of the paintings in the exhibition are untitled, suggesting the artists’ openness and willingness to provide viewers with hints to their subjects and their thinking. Frankenthaler was once asked why she titled her works, and she responded, “Because a title has to have a meaning,” Chanzit notes.

Frankenthaler, seen in her New York studio in 1951, is one of the few well-known female Abstract Expressionists. Photo by Cora Kelley Ward, © 2016 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

While Abstract Expressionism valued freedom, this did not imply a liberated view of gender roles and equality. “As women, we were basically told to go home,” recalls Godwin, who is in her mid-80s and still painting in New York. She studied with the influential German painter Hans Hofmann (as did Frankenthaler) and showed in major galleries in New York. “I stuck around and so did other women,” she says.

Gechtoff began her career in the early ’50s in San Francisco, where the Beat movement encouraged openness and experimentation. She recalls being welcomed into the art galleries on Fillmore Street, including the respected Six Gallery. A few years later, she moved to Manhattan and was shocked to find that the New York art scene “seemed truly closed off to women.” She remembers male artists looking her up and down at parties. “The hostility bothered me so much that I removed myself from the community more than I should have, and I regret that,” she says.

For Krasner, who was married to Pollock, and de Kooning, who was married to Willem de Kooning, their husbands’ fame gave them a certain status in the artistic community, but it also had drawbacks. Krasner, whose work has gained wider appreciation in recent years, lived in her husband’s shadow. “In some cases, the women pushed the men out in front of them,” Chanzit says, “because that’s just how it was back then.”

Although some AbEx artists have garnered more esteem than others, the movement itself has been hailed as a triumph of American painting, and it has been studied continuously since its heyday. For Gechtoff, the AbEx approach is as compelling now as it was when she first viewed Still’s paintings. “It’s an adventure,” she muses, “that’s never ending.”