January 5, 2015Like other exhibitions featuring paintings by the leading artists of the day, “Faces of Impressionism: Portraits from the Musee d’Orsay” offers a feast of visual pleasures for gallerygoers to relish. But this new show at Fort Worth, Texas’s Kimbell Art Museum also goes the extra mile, reminding viewers that, as popular as Impressionism always has been in the U.S., there are aspects of this movement that have yet to be examined. The Impressionists were not just landscape painters par excellence who, while working out-of-doors with portable easels and tubes of oil paint, depicted the transitory effects of light and weather on their canvases. In Fort Worth — which is the only stop for this riveting show — one discovers that they were also accomplished portrait-makers who limned aristocrats and members of the working class; friends and family; musicians, writers and fellow artists, as well as Tahitian women, a Provençal kitchen maid and a clown at the Moulin Rouge so convincingly, you’d recognize all these folks immediately if any one of them happened to cross your path today.

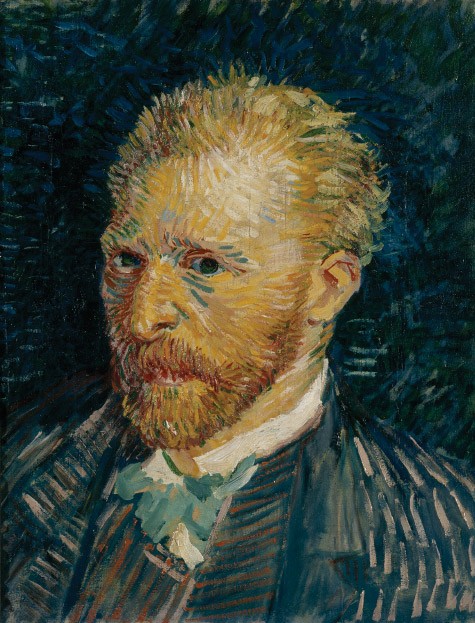

The show, on view through January 25, comprises more than five dozen paintings and a handful of sculptures that span from the late 1850s to the early 20th century, six decades bounded by the period preceding the French Third Republic and drawing to a close before the start of World War I. Paris’s Musee d’Orsay owns a host of treasures, many of which will be displayed at the Kimbell via a new loan agreement between the two institutions. This first edition traveling to Texas features many of the Orsay’s beloved masterworks, including key paintings by Degas, Manet, Monet and Cézanne, along with self-portraits by van Gogh and Gauguin. Standouts also include paintings by less-familiar names like Eva Gonzalès, Frédéric Bazille and James Tissot.

The show’s curator, Kimbell deputy director George Shackelford, knows Impressionism, not to mention the Orsay’s holdings, inside out. Prior to joining the Kimbell, he worked at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and before that he was a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; at both venues he organized many compelling exhibitions, including “Van Gogh: Face to Face,” “Impressionist Still-Life,” “Gauguin Tahiti” and “Degas and the Nude.” Paintings from the Orsay — whose president, Guy Cogeval, is a longtime friend of Shackelford’s — starred in each of these.

Recently, 1stdibs’ Phyllis Tuchman spoke with Shackelford about the creation of the show and its particular highlights.

The vividness of the colors in Édouard Manet’s The Balcony, 1868–69, among other factors, shocked critics when the painting was first presented.

When you organized “Impressionist Still-Life” for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Phillips Collection, in Washington, D.C., in 2001 and 2002, did you know you would one day mount a show of Impressionist portraits?

No, I did not. But portraiture is an abiding interest of mine. In Houston in 1987, I worked on “Van Gogh: Face to Face,” an exhibition that was broader in scope than this one. [The show featured works loaned from multiple institutions and covered the artist’s entire career.] The current show was a wonderful way of grappling with the Orsay collection. It cuts across many artists with superb examples by everyone.

Would the exhibition have been different if you had borrowed portraits from other museums and institutions?

Inevitably, there would have been other paintings, including the Kimbell’s Gauguin as well as our own Cézanne. But if there is one museum in the world from which to do this exhibition, it’s the Musee d’Orsay. You have Degas’ Bellelli Family, Manet’s The Balcony, Cézanne’s Woman with a Coffee Pot and Renoir’s Portrait of Bazille. What I would have wanted to borrow from the Orsay, I now have.

Does your show suggest we should reinterpret Impressionist landscapes?

I’m not sure what lessons we can learn about landscape paintings from portraits. We should be aware, though, that great landscape painters were interested in portrait painting, too.

Having organized exhibitions devoted to portraits and still-lifes, are you making a case for Impressionism’s being less improvisatory and more traditional?

Not necessarily so. When you show Renoir painting Monet, it’s indoors. But it still involves the sort of eye-to-hand magic that we associate with improvisation. And the cliché of improvisation is a bit overstated: Monet was so careful when he was out painting in the landscape. Then too, these are not paintings involving lots of preparatory studies. Often, they’re done straight onto the canvas. The Impressionists were much more careful when they made art than most people realize.

Henri Fantin-Latour’s A Studio in the Batignolles, 1870, shown here, features fellow painter Edouard Manet surrounded by artists and intellectuals, including Renoir, Monet and Emile Zola. Photo by Robert LaPrelle