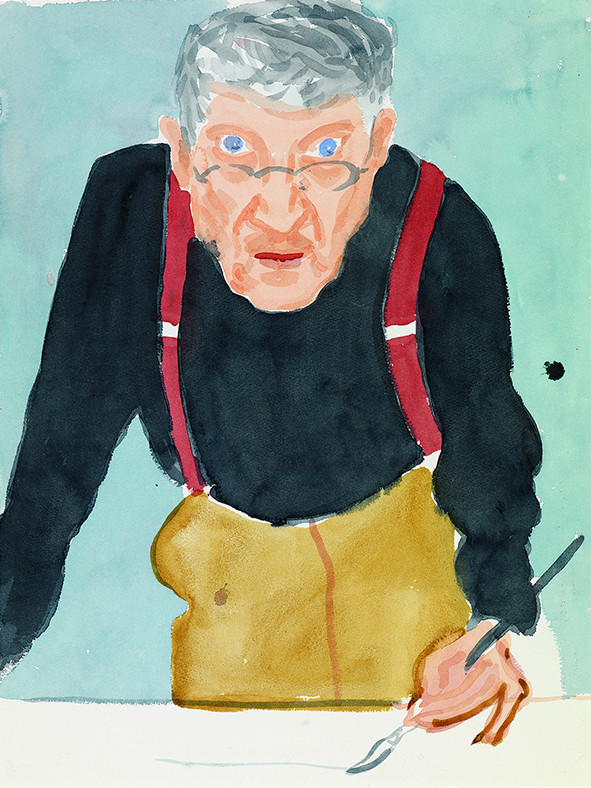

December 12, 2016David Hockney, A Bigger Book, published by Taschen, looks at the long career of the Pop colorist through large-scale reproductions of his art, including rarely seen student works, like this collage self-portrait from 1954. Top: The acrylic painting Garden with Blue Terrace, 2015 (detail), is on the cover (all artwork © David Hockney, photographed by Richard Schmidt, unless otherwise noted).

One way to gauge an artist’s importance is to imagine where we’d be without his or her work. By that measure, it’s safe to say the world would be a much duller place without the paintings of David Hockney.

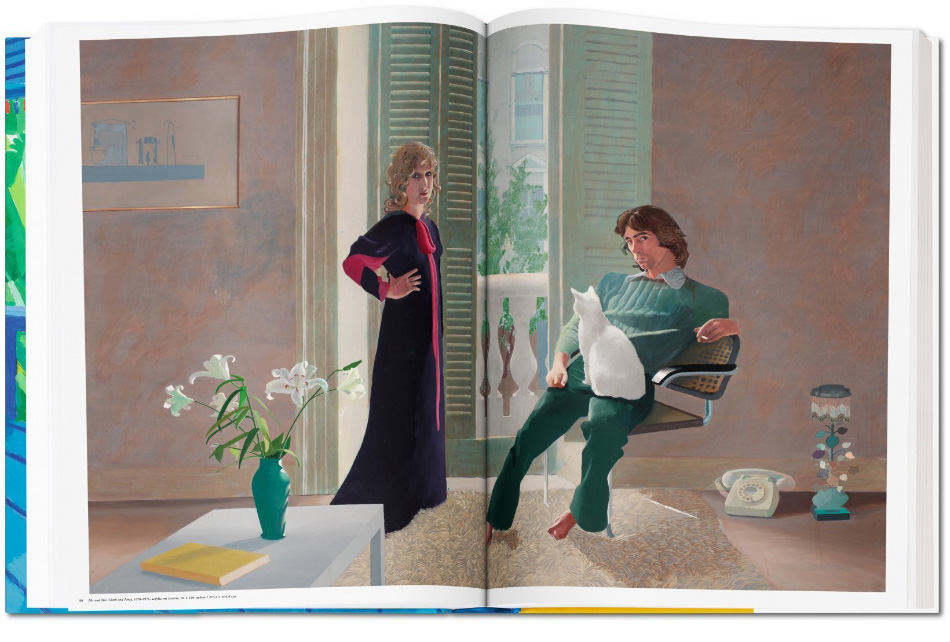

Now 79 years old, the British-born, Los Angeles–based Hockney has managed to do what few other artists have over the past half century: use vivid, intense colors — such as shocking pinks and oceanic blues — as a vehicle for delivering powerful perceptual experiences in the form of portraits, landscapes and more.

Let other artists take up the conceptual mantle of Marcel Duchamp. Hockney has wrestled with the heavy legacies of other 20th-century giants: the great colorist Henri Matisse and the inexhaustible formal experimenter Pablo Picasso.

One book now delivers the full scope of his vision. Taschen has published a supersized (nearly 20 by 28 inches and 77 pounds), or SUMO, volume containing some 450 illustrations. A collector’s edition of 9,000 copies priced at $2,500 comes with a colorful tripod-based bookstand designed by Marc Newson. An art edition of 1,000 copies priced at $5,000 also contains an iPad drawing by the artist.

The tome starts with Hockney’s lesser-seen work from the 1950s and ’60s, when he was a student at the Bradford School of Art, in his hometown, and the Royal College of Art, in London, and extends to the present day. It has virtually no text apart from a facsimile of a charming handwritten note by the artist underscoring that lack: “It is almost chronological and entirely visual,” he quips.

To spend time with the book is to plunge into a sea of color. Hockney’s exploration of blue, or rather the spectrum of hues encompassed by the term, proves especially dazzling. As early as 1954, in a bleak ink drawing called Railway Yard, he used a wash of denim blue to set a male figure apart from the industrial landscape — a hint of personality in a gray world.

A Bigger Book comes in a collector’s edition of 9,000 copies with a colorful bookstand designed by Marc Newson. An art edition of 1,000 copies also includes one of four iPad drawings.

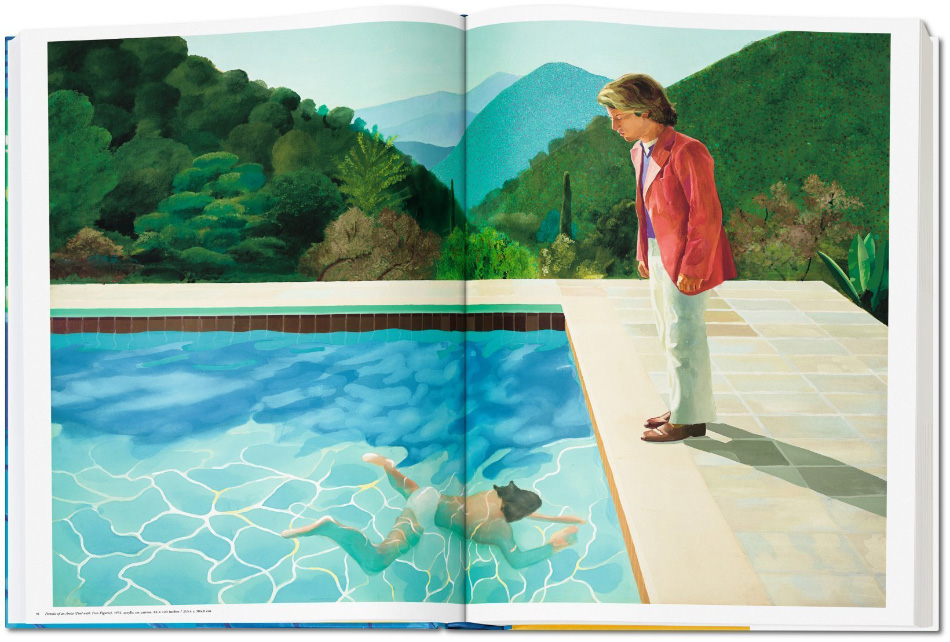

Hockney’s first trip to Los Angeles, at age 26, famously unloosed a flood of colors, inspired by the green of the palm trees and shrubs, the bright blue skies and the play of sun on the surface of swimming pools. If painters like Edgar Degas, a century earlier, captured the beauty of a female bather through her softly blurred flesh tones, Hockney expressed the grace of a male swimmer (also shower taker) through the clean lines of his torso against the smooth blue ceramic tiles.

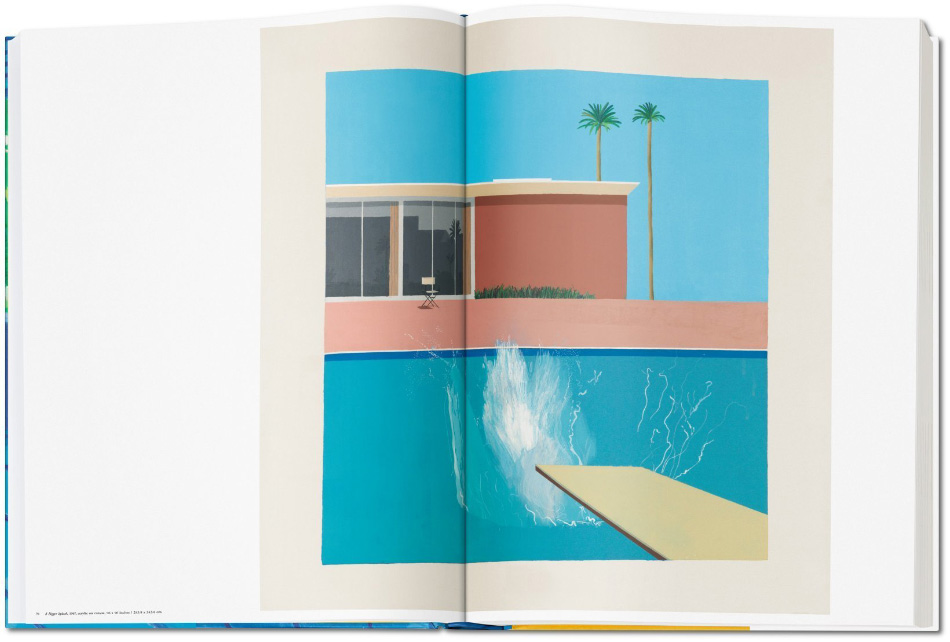

Hockney’s discovery of acrylic paint soon after his move to California gave him an even more vibrant palette to work with, as in the cobalt- and ultramarine-fueled 1967 masterpiece A Bigger Splash. The unpeopled picture shows, in front of a boxy mid-century house, a pool that seems designed to contain or even tame the reflection of a palm-tree-laden landscape. Its smooth surface is disturbed by a single splash, whose source is nowhere in evidence. The painting is a study in sublimation, inviting us to ask what lies beneath the surface. It is also a study in competing colors: the turquoise-tinted water versus the truer blue of the sky.

A Bigger Splash belongs to the Tate Britain in London, one of several major international museums that have collected Hockney’s works over the years, and is sure to be a centerpiece in the museum’s exhibition of the artist’s oeuvre, opening in February 2017. In small reproductions, the yellow diving board in the corner can look like a decorative touch. In the Taschen book, as in person, it seems like an invitation to take a plunge.

“You can’t do a book like this with a lot of artists,” says Benedikt Taschen, who has previously published SUMO editions devoted to Helmut Newton, Annie Leibovitz and Sebastião Salgado. “But I think Hockney is the most important living painter. And his paintings come alive at this size in a very different way — you can have a real experience with them.” At the Frankfurt Book Fair this year, Hockney noted, beaming: “We did seven or eight color proofs, and I think these reproductions are the best I’ve seen.”

Hockney’s first trip to Los Angeles, at age 26, famously unloosed a flood of colors.

A neighbor of the artist in the Hollywood Hills, Taschen appears in the book himself in a 2013 seated portrait. It appears in a section that breaks from the format of one or two paintings per spread to offer a full grid of 18 portraits, among the artist’s more recent projects, at a glance.

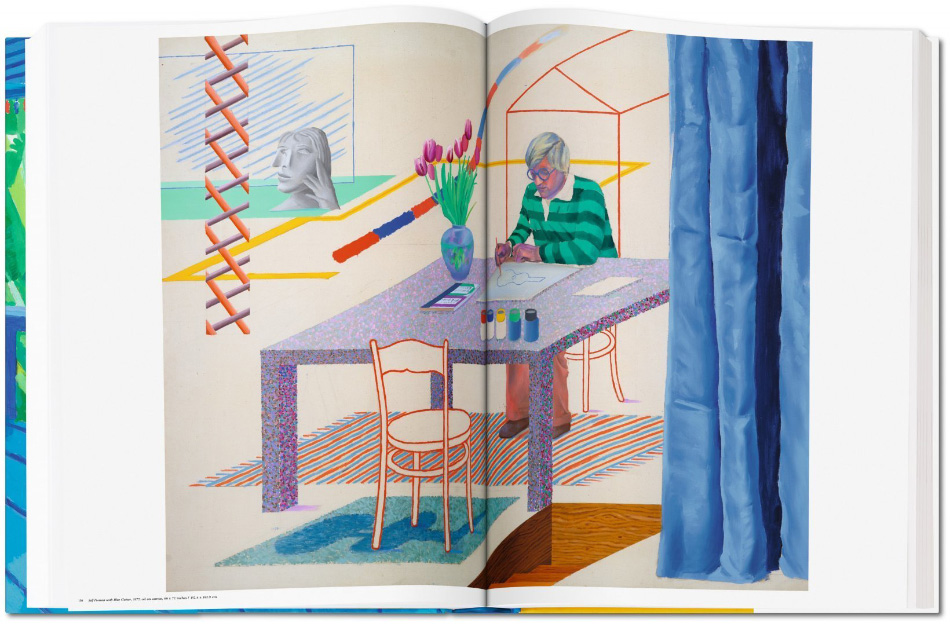

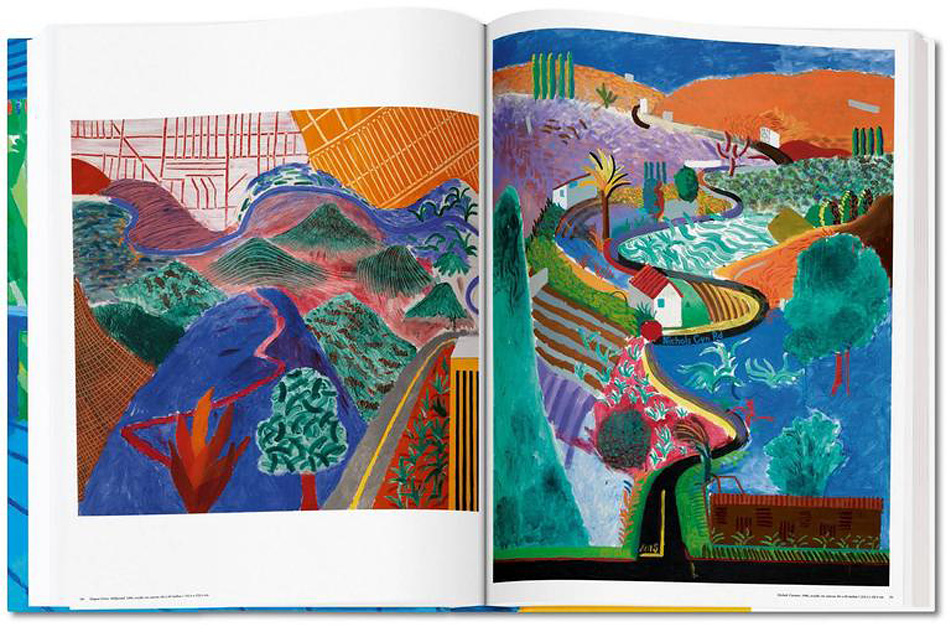

This portrait gallery effect is just one advantage of printing at this scale. Another is that Hockney’s attempts at upending Renaissance conventions of linear perspective, with its single vanishing point, are more effective seen large than in a smaller size, where depth cues can be misread or overlooked.

The 75-pound volume contains almost no text, only a handwritten note from the artist: “It is almost chronological and entirely visual,” Hockney quips. Photo by Matthias Vriens-McGrath

Hockney’s intellectual interest in linear perspective is widely known from his 2001 best seller, Secret Knowledge, in which he argued that its invention — and with it so much of Western art history — stemmed from painters’ use of shaving mirrors and other optical devices. In his own work he has experimented with multiple vanishing (also vantage) points.

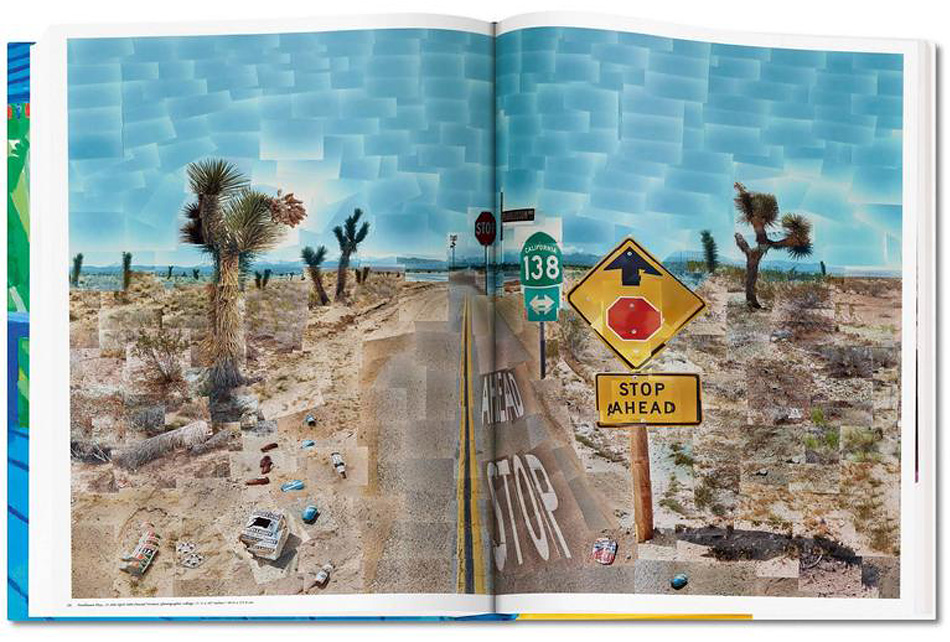

For instance, for his composite Polaroid series from the 1980s, he collaged dozens of photographs taken from different viewpoints to create a panoramic, but also highly dynamic, landscape. At full or even larger-than-life size, the book’s reproductions create the same sort of push-pull visual effect as the original photo collages.

Describing a digital-photo-based tableau, Perspective Should Be Reversed, from 2014, Hockney says he used multiple photographs to get not one but “many vanishing points. It is this that I think gives them an almost 3-D effect without the glasses. I think this opens up photography into something new.”

Like his photo collages, the paintings that refuse to act like windows onto a single view are especially powerful at large scale. The 1985 A Walk Around the Hotel Courtyard, Acatlan, with its bold reds and dramatic overhangs recalling his operatic stage designs of that decade, disrupts conventions of perspective by bending the architectural right angles. The picture offers, maybe even compels, multiple points of entry. To view this courtyard is to wander through it — much like the Taschen book itself.