October 16, 2017When it comes to American jewelry, the little blue box (and its contents) have uncontested primacy. But there is another treasure that has marked manifold milestones, from graduations to anniversaries and everything in between: the cable-styled jewelry of sculptor-turned-jewelry-designer David Yurman. Over the past four decades, his powerful silver and gold bracelets, rings, pendants and earrings expressing this industrial motif have become icons of American design, and a new book, Cable (Rizzoli) looks back at its origins in downtown New York’s red-hot art scene of the 1960s and ’70s.

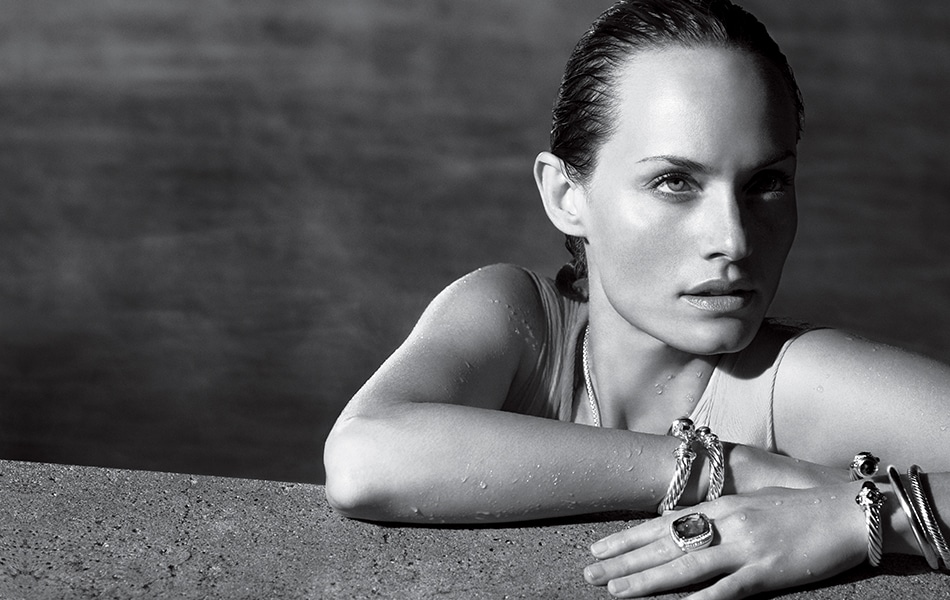

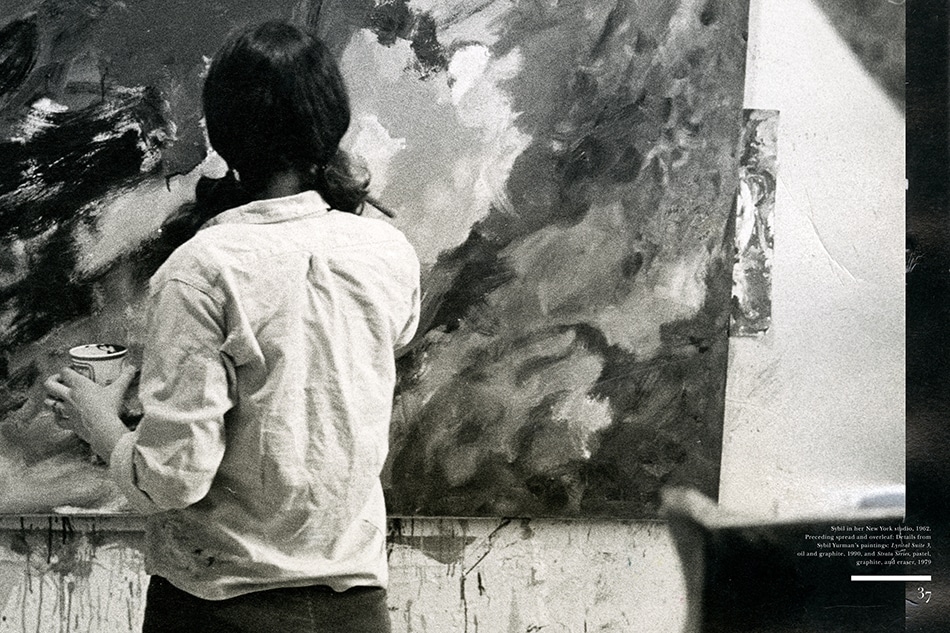

Sybil and David Yurman met while working at a sculpture studio, and the first piece he made for her was a linked belt that she still owns (portrait by Peter Lindbergh). Top: A collage of snapshots, jewelry renderings and prototypes offers a glimpse into the Yurmans’ journey from struggling artists in 1960s New York to creators of an iconic jewelry brand (photo by Nathan Copan).

But the book also goes beyond the pieces, with contributions from art historian Paul Greenhalgh and legendary editors William Norwich and Carine Roitfeld. It also tells the story of Yurman and his wife, Sybil, who serves as the company’s chief brand officer, as they made their way from budding downtown artists to the cofounders of a modern jewelry empire. Just in time for the pair’s 75th birthdays (his this month, hers in December), Introspective sat down with the couple to discuss those beginnings and how one necklace grew into many.

This rendering for the prototype of the Renaissance cable bracelet was created in 1982. Photo courtesy of the David Yurman Archives

You have described your business — and your relationship — as “one big art project.” What was it like for the two of you to go back in time and revisit all these memories for the book?

David: For me it was cathartic. I kind of didn’t want to do the book. I like just moving forward and occasionally looking back at old drawings. I don’t want to relive my life. But it was rather emotional.

Sybil: In the 1960s, you literally lived to do your work. You didn’t really spend time doing anything else. It was your vision and your way.

The era’s ethos was epitomized by Stewart Brand’s 1968 The Whole Earth Catalog, to which the V&A’s recent exhibition “You Say You Want a Revolution” devoted an entire section. Did you follow the book’s philosophy?

Sybil: It was really what we all were talking about, like eating healthfully and making things for yourself. David had an arrangement where we would get baked breads and cakes every Saturday in exchange for jewelry. There was a lot of trading going on.

David: The Whole Earth Catalog was the bible of how to survive away from the constraints of what society wants you to do. But Sybil and I did not really want to live that alternative lifestyle. At the craft fairs, everyone would show up in these old VW vans wearing tie-dye, and we were coming out of the city in a 1964 black Cadillac with the seats knocked out of the back. We were definitely still New Yorkers. We were sharing granola, but that’s about it.

David, the new book highlights some of the techniques you used early on, like direct welding. Do you still use that technique?

David: Yes, I set up my welding table again. I think there is a picture of me in the book sitting at [it], maybe in the mid-seventies, and I hadn’t welded or brazed since then. But I actually made a piece last summer. I like that experience. It’s super-focused, it’s super-intense, with the heat, melting and puddling and controlling the puddle of bronze into a shape. The idea of making things is really the most important thing for me. It’s a wonderful meditative connection.

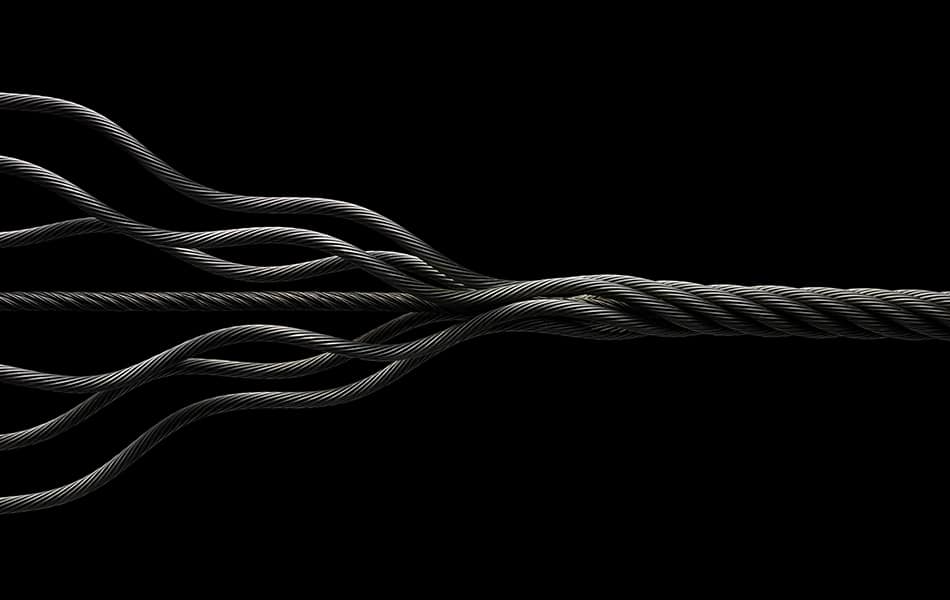

“There is a life rhythm with cable,” David Yurman says in the book. “Like DNA, it brings form to life.” Photo by Nicholas Alan Cope

You apprenticed under quite a few people, and not just in direct welding. What other materials did you work with in your early years?

David: I was a sandal maker for about seven years. I went to Provincetown to visit my sister over the summer when I was in the eleventh grade. She was with a Cuban sculptor, Ernesto González, who taught me how to do direct weld. I also met a guy there named Roger Rileau, who was a master sandal maker. He was an interesting man, and he was kind of a father figure in a way. So, I hung out at his studio, and I stripped leather and did outlines and built arches. And then, when I went to NYU, I worked for Dick Whelan in a leather shop in the village. Hanging out at the leather shop was like hanging out at a barber shop. The good part about it was that I could travel almost anywhere and get a job making sandals.

Sybil, you also had a peripatetic young adulthood.

Sybil: I ran away from home when I was sixteen. I wanted to leave the Bronx, so I went to San Francisco, where I met Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady and Michael McClure. It was an incredibly creative time. Cassady would come by and see that I was drawing, and he would bring me paints. Later on, I went to Berkeley, where I worked at the student union and was auditing classes with Peter Voulkos, who is a father of American pottery. From there, I went to Washington, D.C., and got a job working with potter Shoji Hamada as his studio assistant. When I moved back to New York, I began working for a group of sculptors, and one of them was David. We started spending more and more time together. I was working on bracelets at the time, and he was helping me.

David: I was teaching her how to make patinas, but it wasn’t really about that. It was a lot of emotional connection.

“The best model is the one who understands that a great picture can become even better if you give something from inside. … The David Yurman girls — Kate, Amber, Natalia and Gisele — all have this quality,” legendary fashion editor Carine Roitfeld writes. Here, Kate Moss wears a crossover bracelet and a cable pinky ring. Photo by Peter Lindbergh

Wasn’t your first piece of jewelry for Sybil?

David: It was actually a belt, and I still have it. Sybil would have sold that if she could. She’s all about the business.

Sybil: We were going to a party, and I went to his loft first. I was coming from work and had to change my clothes, and I told him I forgot my belt. And he said, ‘No problem, I’ll make you one.’ I was incredulous. But he went to the welding table and proceeded to make a belt, with all the links. And I watched for a while, and then I started reading, and then I got hungry….

David: And then it was midnight!

Sybil: And then we didn’t go out, and he got a reward!

David: Time management is not all it’s cracked up to be. You can’t put a deadline on creativity.

Sybil: Shortly after, I wore a necklace to a gallery, and the woman there asked where I got it. I told her David made it for me. She asked if he could make more. He said no, and I said yes. He thought I was going to sell my necklace, but I wasn’t going to. By the time we got home, she had sold four of them. That’s how it all started.

Your son, Evan, is an integral part of the business, recently promoted to creative director. When did he start designing?

Sybil: From a young age, he would do drawings, and he made pieces. We lived in a loft on Franklin Street, and we had this ten-foot-long dining room table. We used three-quarters of it for drawing and books and things that interested us. After dinner, David and I would draw. When Evan got up in the morning for breakfast, he would look at David’s drawings and try to make something similar.

David: He was my critic. He still is.

You introduced the cable bracelet in 1983. After all these years, what does the motif mean to you?

David: I feel strength and harmony. And I think love is about harmony, working together and being intertwined. It’s about this harmonious form.

Sybil: Very early on, I said to David, “It’s the river that runs through everything.” It gives us parameters, it gives us a structure. It’s constant. Then, we do things to change it, move it, push it. It’s always within that concept. It’s about those same wires that David was designing with when he was making sculptures with molten rods.

How do you maintain your artistic vision while having a hand in growing the company over the past thirty-seven years?

Sybil: I was always involved with the visual language and dialogue, trying to convey the brand message. And the brand message was really not about a brand. The message was our aesthetics and doing it our way. When we first started doing ads, there was nobody doing it like we were doing it.

David: We are a part of everything. It’s an all-encompassing sense of aesthetic. Either you get it, or you don’t. And you know what’s right when you see it. Everyone has an aesthetic, and everyone has a feeling of bringing things around and to make them feel good.