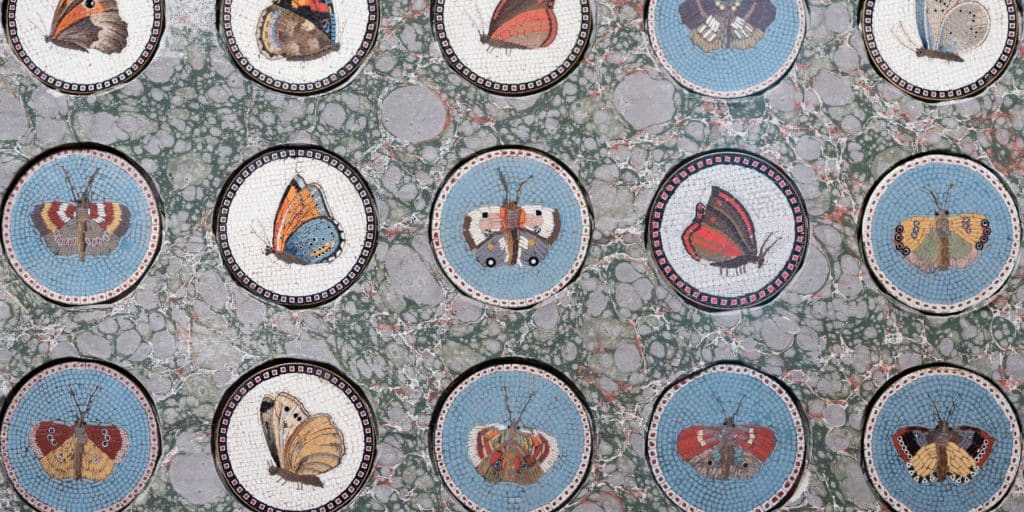

This 19th-century micromosaic parrot pendant, set in 19-karat gold by an unidentified artist, is adorned with rare gems, such as tsavorite and demantoid garnets. Top: Designer Elizabeth Locke’s collection of 20 19th-century micromosaics depicting various butterflies, in the original box. All photos courtesy of Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

It’s a familiar tale. Like countless travelers before her, Elizabeth Locke had an artistic encounter in Italy that remained with her long after she returned to New York to pursue a publishing career. In the early 1970s, while enrolled in a graduate program in Italian literature, she discovered, in a distant corner of Il Museo degli Argenti, in Florence, a collection of small artworks — most not more than two inches wide — composed of enameled-glass tesserae.

This art form, micromosaics, is the miniaturized offspring of a type of decoration used to embellish buildings as far back as 2500 BC. The pieces Locke saw rendered ancient Roman architecture and classical scenes with hundreds (or thousands) of individually placed fragments. She was fascinated by the painterly detail of imagery executed on a scale so small the makers employed microscopes.

Elizabeth Locke’s namesake jewelry line draws on inspirations ranging from 19th-century Italian micromosaic and pietra dura works to 18th-century Chinese gambling counters and Essex crystals.

When Locke founded her signature jewelry collection, in 1988, her designs merged her affinity for antiquities with an unfussy modern sensibility. She put a global mix of artifacts — Venetian-glass intaglios made from 17th-century molds, ancient Roman coins, Japanese porcelain buttons — in handmade, sometimes gemstone-studded, 19-karat-gold settings. She extracted elements from Roman, Etruscan and Greek jewelry, including granulation and hammered textures, and made them relevant to a contemporary eye. All the while, micromosaics remained on her mind. After sourcing a few in London, some of which she reset in 19-karat gold and sold to clients, her transition from admirer to collector had begun. In the following decades, Locke acquired 92 micromosaic works that, she says, “were particularly fine, had unusual subject matter” or evoked a “sentimental attachment.” These pieces are the subject of the exhibition “A Return to the Grand Tour: Micromosaic Jewels from the Collection of Elizabeth Locke,” at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA).

They are time capsules from the era of the Grand Tour, a rite of passage, mostly for English men, in vogue from the late 18th through much of the 19th century. During that period, travel to continental Europe, especially Italy, was the capstone of one’s cultural education and conferred social status. Often accompanied by retinues of retainers on journeys lasting months or years, the elite travelers required artful personal mementos befitting the experience.

A teacup from a micromosaic tea service crafted by the Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur (Royal Porcelain Factory) Berlin in 1815.

Grand Tour micromosaics arose from the entrepreneurial impulses of artisans who had trained in the Vatican’s workshops. They set up stands in the neighborhood surrounding Rome’s Spanish Steps, where most tourists resided, selling small ready-made compositions and taking commissions for custom works. The majority of micromosaics are unsigned, although Locke’s collection does include examples from acknowledged masters, like Gioacchino Barberi and Giacomo Raffaelli.

After making a purchase, patrons took their mini masterpieces to jewelers or artists to have them set in jewelry, frames or decorative objects like paperweights. A few pieces in the exhibition retain their antique settings, but most were reconfigured by Locke into new jewelry designs that she wore herself, like brooches, rings, pendants and earrings. They’re all set in the signature textured 19-karat gold that characterizes her namesake jewelry line.

The VMFA exhibition is organized according to themes that fascinated travelers of the period. These include historic Roman architecture, such as the Colosseum, St. Peter’s Square and the Forum, as well as figures like Romulus and Remus and the lion of St. Mark. Also represented is “the idea of the romantic landscape and flowers as a medium of language,” says Susan Rawles, associate curator of American painting and decorative art, who organized the show. Images include a profusion of hounds and spaniels, butterflies and insects, owing to the popularity of pets and amateur entomology among the travelers.

One of Locke’s 19th-century micromosaic brooches depicts the forum, the center of daily life in Rome during Roman Empire. The hammered-gold mounting is set with cabochon and faceted aquamarines.

Part of the appeal of assembling a collection of micromosaics is the thrill of the chase. “They’re very hard to find, and you never know where you’ll see them,” Locke explains. Private dealers in Europe, auctions and off-the-beaten track antiques shows have all yielded exceptional finds. “Elizabeth has really trained her eye and is very careful about the work she acquires,” says Rawles, who notes that Locke’s pieces are some of the finest in the world.

The cobalt-framed micromosaic in this rectangular pendant, topped with three cabochon blue sapphires, depicts the Tomb of Cecilia Metella, a mausoleum built just outside Rome in the 1st century BC. Matella was the daughter of a powerful Roman consul and the daughter-in-law of Marcus Crassus, who served under Julius Caesar.

Despite the ambition of her collection, Locke never dreamed her holdings would end up in a museum. During a visit to her home, in northern Virginia horse country, VMFA’s chief curator and deputy director for art and education, Michael Taylor, asked to see the pieces she had amassed. His response, Locke recalls, was “Looks like an exhibition to me.”

Locke has entrusted her trove to a highly respected institution. Located in Richmond, VMFA houses the largest museum collection of Fabergé and Russian decorative arts in the U.S., Bunny Mellon’s cache of Schlumberger jewelry and a well-regarded assortment of English silver. Moreover, it is open daily, with free admission, no less.

Locke hopes that the exhibition will be a reminder of the importance of handmade artistry. Placing her prized micromosaics with the museum is a way to maintain them as a source of inspiration for future creators. “It took me more than thirty years to assemble them, and I didn’t want pieces sold bit by bit,” she explains. Meanwhile, Locke sees an acquisitive opportunity in relinquishing the pieces: “I can start collecting all over again.”