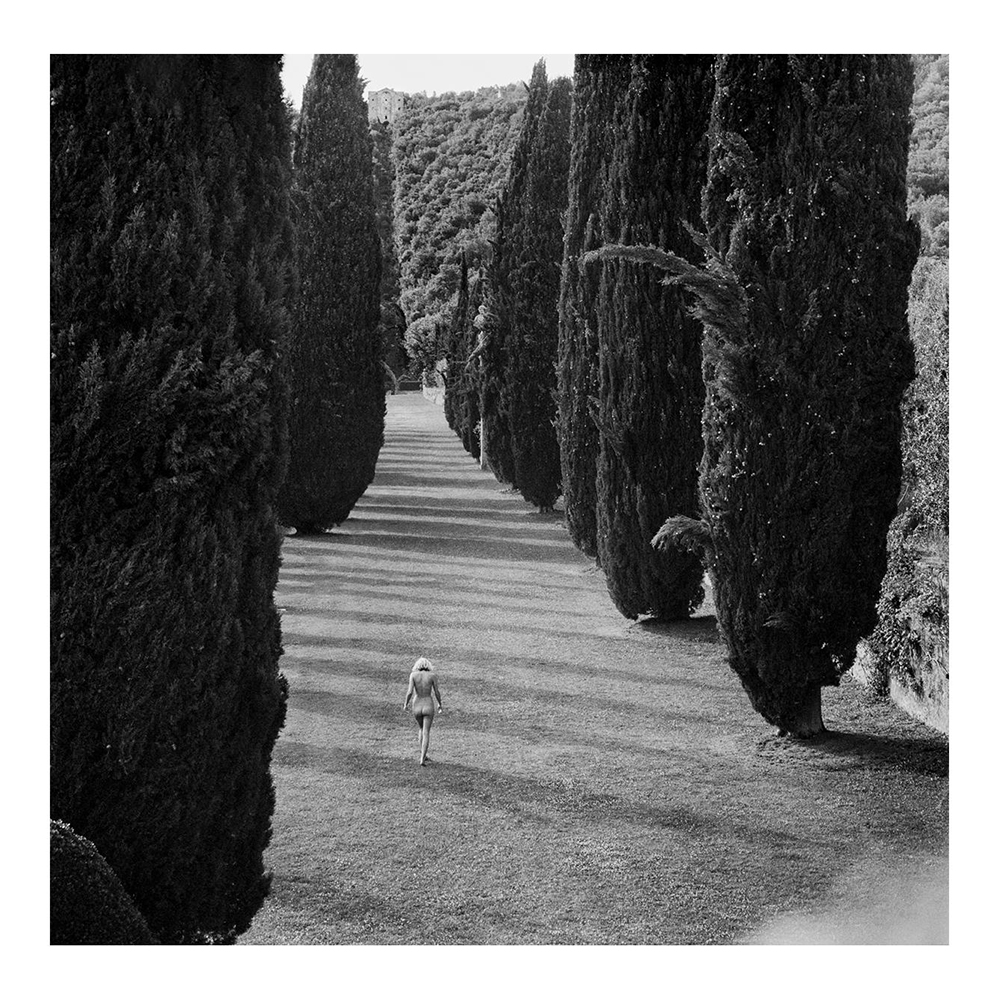

January 23, 2013A new volume showcases the many colorful characters photographed by Jonathan Becker for Vanity Fair over the past 30 years, including Madonna, Martha Graham and Calvin Klein (October, 1990). All images courtesy of Assouline, © Jonathan Becker

Over three decades portraying those who matter — the rich and the powerful, the artistic and the famous (not to mention the notorious) — for Vanity Fair, Manhattan born-and-bred photographer Jonathan Becker has led a beguiling visual voyage through society, offering new insights into some very familiar faces. An arresting portfolio of this work, now collected as Jonathan Becker: 30 Years at Vanity Fair (Assouline), is a chic, eye-opening blockbuster of a book.

In an informative and amusing introduction, VF editor–in-chief Graydon Carter fills in facts about Becker’s talented family: his Rhodes Scholar father, Bill, who founded Janus Films and the Criterion Collection (a pioneer in offering classic and foreign films on DVD); his Broadway dancer-turned-choreographer mother, Pat; his restaurateur sister, Alison, of Alison’s on Dominick fame.

And Becker himself? “I bailed out of academia,” he says. But while bailing back in for a summer session at Harvard, he wrote an essay about Brassaï and Surrealism that led him to his mentor — the legendary Hungarian-born, Paris-based Brassaï himself — and, ultimately, his métier as a photographer.

Back home, fame wasn’t instant. He drove a Checker cab while covering events as a freelancer. But his genuine interest in and ease with his subjects, his boyish grin and puckish charm and his zest for both creating and capturing the unexpected ensured his eventual success in portraiture.

From a romantic shot of waltzing Le Bal debutante Marie-Solène d’Harcourt to the knockout portrait of fashion high-priestess Diana Vreeland at home in her red salon (she called it her “Garden in Hell”), his body of work represents, as Carter writes, “a portrait of an age — tiaras, chalk-stripes, warts and all.” To this day, Becker shuns digital wizardry, preferring to shoot with film on a Rolleflex. Confirming the documentary nature of his work, Carter goes on to describe Becker as “one of the finest portrait journalists of our time,” a “throwback” to the glory days of the grand-name photographers.

Recently, in an interview with Introspective’s Jean Bond Rafferty, Becker spoke about how it all came to be.

From left: Tom Bolan, Rupert Murdoch and Roy Cohn at a party during Ronald Reagan’s inauguration, Washington, D.C. (January 21, 1985)

BY YOUR ESTIMATION, YOU’VE DONE MANY HUNDREDS OF ASSIGNMENTS FOR VF. SO YOU HAD A MASSIVE AMOUNT OF WORK TO CHOOSE FROM FOR THE BOOK. HOW DID YOU DECIDE WHAT WOULD MAKE THE CUT?

I’ve long been working on another book that will encompass all of my work — a beautiful book, but always unfinished. Then my son Sebastian said, “You do have to publish a book, but it doesn’t have to be a magnum opus.” I realized how to limit it: thirty years at Vanity Fair. My archive is very organized. From memory, I knew which images were the strongest, the things I liked best and pictures that for one reason or another never got used to full advantage in the magazine. The photo of Roy Cohn and Rupert Murdoch, for example, was published at about three inches square. And the one of actress Patricia Neal … You didn’t really get the impact. I knew I had stunning pictures, and they were easy to identify because there was a little pain involved when I realized I’d done something wonderful and it appeared small.

Brooke Astor and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., at a lunch for the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York (May 18, 1983)

CAN YOU REMEMBER SOME SHOOTS THAT WERE REALLY FUN? THERE ARE A LOT OF PHOTOS OF PEOPLE LAUGHING — ANNA WINTOUR, FOR EXAMPLE, IS ABSOLUTELY BEAMING. GRAYDON PUTS IT DOWN TO YOUR SORT OF JACQUES TATI STYLE, ALTHOUGH I DON’T SEE YOU AS TATI-ESQUE. I FEEL MANY OF YOUR PORTRAITS ARE MORE LIKE REPORTAGE THAN POSED PICTURES.

Well, I do sometimes fling things around if I think it disarms people. But “fun” is the wrong word. I enjoy my work endlessly when I’m doing it. And when it’s done, it’s very fulfilling. Of course, it can be torture. Sometimes, to convince a reluctant subject, it takes hours and hours of talking.

Research, understanding and any kind of personal identification or common ground with the subject is unbelievably important. That is where I have some talent because I do know how to connect with people. You have to be actually interested in the subject. Really, really, honestly.

In writing, you can go back and reflect. In photography, you don’t. Once that button is pushed, you’re done. Sometimes I don’t even know what I am doing consciously, particularly in situations like an event where there are lots of people around. At the same time I’m always looking for photographs within those situations that are interesting to me, things that are revealing themselves. I am seeing things and it registers on a level that is purely visual, but with an understanding of what is happening, like that picture of Robert Mapplethorpe shortly before he died. If it had been composited and retouched, it would be utterly worthless. Someone else might have tried to take away all those horrible marks on his face, clean it up so it was an elegant-looking Robert Mapplethorpe holding court. And he would have preferred that. When he saw the photo, he said, “It’s horrible, like Diane Arbus.” Which was a great compliment.

Hungarian-born photographer Brassaï in the Place Denfert-Rochereau, Paris, on the day Becker met him (November 1974)

YOUR MEETING WITH BRASSAï WAS A PERSONAL TURNING POINT. THE BOOK OPENS WITH HIS PORTRAIT. I SEE IN HIS EYES THAT HE’S INTERESTED, BUT HE’S LOOKING AT YOU SOMEWHAT WARILY. TRUE?

That’s absolutely true. That photo was taken the day we met. I got a letter from Brassaï in response to a paper I’d written, which his friend, my professor, had forwarded to him. I wrote back and told him I just happened to be coming to Paris. The letter he had sent me was so important that I wanted to know him. So I came to Paris and eventually we got to be very good friends, and I helped him get The Secret Paris of the ’30s published. But at this point he didn’t really know me. The Brassaïs were very careful, they didn’t have a lot of friends.

What intrigued me about his work was the humor in it, the juxtapositions that are ironic. Much in it is surreal. He was a painter and a sculptor who came to photography. He knew the subject that he wanted to document — this whole underworld of Paris — but could never figure out a way to get at it by painting. Not knowing specifically what you want but knowing what you are intrigued with is very important. In two years, he made one of the great bodies of work of all time, Paris by Night.

Janet de Cordova, San Luis Potosi, Mexico (February 26, 2009)

YOU’RE VERY GOOD WITH GRAND DAMES AND CRUSTY MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE. I LOVE THE PHOTO OF JANET DE CORDOVA WITH HER PILLOW EMBROIDERED “NOT TONIGHT.” HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE YOUR WORLD AND YOUR PARTICULAR TAKE ON IT?

Janet was a great story. She was the toast of Beverly Hills, the wife of Freddie de Cordova, the producer of Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. They gave great parties, had a wonderful house. When he died, she carried on, looked after by her housekeeper, who one day said, “I’ve built a house in Mexico, and I’m retiring.” Janet had a fit. “You can’t leave me — I’m coming with you,” she said. She sold her house and built another story on top of the maid’s house in this little town in Mexico, then replicated her old boudoir. That’s where I took her picture.

There is a crossover in my world between the dance and show world of my mother, the purely social world of family summers in Southampton and then there were the movie people, and all the writers my father was friendly with. He was at Harvard with George Plimpton, and they were bosom buddies. George was like a godfather to me, a wonderful generous man and very encouraging. I really miss him.

I’ve kind of perfected my way of looking at my world. I’ve just taken to documenting what happens. Dennis Hopper, for instance, I knew he was dying and that his family was going to be around. Everyone was convoked for the photograph. And it turns out, they were all pleased to be photographed in such a moving way with their patriarch at death’s door. It was bittersweet, an almost happy time.

As dapper as he is discerning, Becker is captured here by another celebrated photographer, Ralph Gibson

YOU ARE A REGULAR ON THE VF INTERNATIONAL BEST-DRESSED LIST. DO CLOTHES MAKE THE MAN — AND HAVE AN EFFECT ON YOUR SITTERS?

Early on, I discovered that the impression one makes with one’s clothes is more valuable than a PhD. At [the Manhattan private boys’ school] Buckley, I was told that the way you looked was important to how you represented the school. The way I represent Vanity Fair and represent myself is important. I got into tailors very young, and I like having my own clothes made for me. If you show up for a portrait looking put together, it’s respectful. So the subjects take the whole sitting more seriously. For me it works: I feel better, and they do, too.

Growing up with all the dance and movie people around — and this goes to the very heart of my work — I am convinced that I see everything, positively everything, as theater, including me taking the picture. It’s all encompassing, part of the experience. So I dress for it.

Purchase This Book

Or Support Your Local Bookstore