August 8, 2021“I roll with the punches — I found my silver lining during the pandemic,” says photographer Jonathan Becker. During the lockdown, the Manhattan native, best known for his distinguished 40-year career at Vanity Fair, transformed his Bedford Hills storage space, located in a former bank building near his home in Upstate New York, into a working studio, where he and his team now produce museum-quality archival pigment and platinum palladium prints. “We create the very best prints possible in limited editions,” he says of this historical series, which has recently become available on 1stDibs.

The collection provides a taste of Becker’s prolific output, with its eclectic range of fascinating sitters — among them, legendary choreographer Martha Graham, Chinese artist-activist Ai Weiwei, American philosopher Cornel West, godfather of gonzo journalism Hunter S. Thompson and euthanasia proponent Jack Kevorkian. However, it’s when we train our lens on Becker’s own colorful career that we get a true measure of his genius and fearless perfectionism, nurtured through his encounters with 20th-century editorial and artistic luminaries.

Bea Feitler — the late, legendary artistic director responsible for vamping up Harper’s Bazaar and Rolling Stone in the 1960s and ’70s — gave Becker his first big break, in 1981, when she asked him to submit images for the relaunch of Vanity Fair.

Becker, who was 26 at the time, had already developed an enviable reputation as a portrait photographer working on Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine and alongside Slim Aarons and Norman Parkinson at Town & Country, although he knew not to step on his famous colleagues’ toes. “I was a young little interloper,” he says. “I learned more by listening and watching those giants than by trying to engage in any direct interactions with them.”

By this age, too, Becker had forged a close friendship with French-Hungarian Surrealist photographer Brassaï, who was then in his 70s. “Brassaï was more than a mentor to me. He thoroughly enriched my perspectives on art and myriad aspects of life,” Becker explains. “His unique artistic interpretation of what he saw before pulling it through his lens was stark and pure to his own experience. I was inspired by his tremendous focus and found a surreal and often subtly humorous element to his work, which fascinated and intrigued me.”

How exactly Becker became acquainted with Brassaï merits a brief digression, since the connection proved pivotal in helping him to secure the Vanity Fair project.

At 18, Becker took a class at Harvard Summer School. “It was an enticing comparative literature course on Surrealism taught in French to postgraduate students,” he says. “Despite my then-spotty French, I was deeply intrigued with the Surrealist movement and how it relates to photography. I eventually wrote a paper on Brassaï, whose work I greatly admired.” Becker handed in his essay so late that he flunked the course. But his obvious enthusiasm for the subject impressed his professor, who knew Brassaï personally and encouraged Becker to send him the essay.

Upon reading the piece, the avant-garde photographer, who was based in Paris, wrote back with words of great encouragement. “Brassaï said that I had given him ‘une grande satisfaction’ and that I had ‘understood and expressed the spirit’ in which he photographed,” Becker recalls, adding that to this day, he keeps this cherished letter locked away for posterity.

The correspondence gave the young man the push he needed to pursue his career in earnest. “My first ever assignment was for Interview magazine in New York. The portrait was of Jill Robinson, a writer and the daughter of the great playwright and Hollywood mogul Dore Schary.” says Becker, who was then still in his teens and didn’t get around to making what would be a life-changing trip to Paris for a couple of years.

When he did eventually leave for the French capital, in October 1974, he rented a modest chambre de bonne (maid’s room), recently vacated by New Wave cinema star Jean-Pierre Léaud. The rental had been secured by Becker’s father, William, who was well-connected in Europe thanks to his work as a film distributor specializing in art-house and foreign movies. “I spent my twenty-first birthday in Paris at Jean Seberg’s place. I got around — here, there and everywhere — in those starry circles!” says Becker, laughing. He studied under Brassaï for a year, the longest his plane ticket would allow, and the two remained in close contact until the artist’s death a decade later.

In France, Becker was busy on the job front, too. “I became the first Paris-based photographer for W magazine, which led to all kinds of interesting work taking pictures of actresses and French New Wave pioneers like Louis Malle.”

This brings us full circle to 1981, since the pictures Becker submitted to Bea Feitler, which were published a year later in the relaunched Vanity Fair, were portraits of Malle and Brassaï taken during those halcyon days. The young photographer, who was moonlighting at the time as a New York City cab driver, hadn’t dreamed that the project would put his pictures on an equal footing with those of legends of the medium: Also contributing to this debut edition were some of photography’s most revered names, including Richard Avedon, Irving Penn and Helmut Newton, as well as rising star Annie Leibovitz, whose popularity had recently skyrocketed, thanks to her Rolling Stone cover picture of a naked John Lennon curled up alongside a fully clothed Yoko Ono.

That issue was a game changer in modern magazine publishing, with Vanity Fair setting the bar for engaging editorial and daring design for decades to come. It also signaled the making of a man: Becker’s talent for visual storytelling shone through in his avant-gardist tribute, and the magazine’s creative team kept him on, marking the start of his long career there.

As a regular Vanity Fair contributor, the photographer operated in the highest echelons of society, traveling the world and immortalizing countless A-list movers, shakers and thinkers from the fields of fashion, culture and politics, not to mention royalty. In 2001, he famously shot the first photograph showing the Prince of Wales and Camilla Parker Bowles together, at Buckingham Palace.

More adventurously, in 1995, he traveled to the depths of the Amazon jungle to photograph the Yanomami tribe. It was an assignment from Graydon Carter, whom Becker calls “a fantastic and original editor” (his fourth at Vanity Fair) and who remains a close friend. “I thought he was trying to get rid of me!’ ” says Becker, chuckling. “The Yanomami had a wonderful sense of humor, but of course, their customs were totally unfamiliar to me. In the middle of the night, they would dance around our hammocks chanting with spears.”

Becker was arguably better equipped for the experience than most: Between 1991 and 1994, he was lead photographer for the Rockefeller Foundation, documenting the organization’s philanthropic projects across five continents.

With a style at once impactful, reflective and irreverent, Becker belongs more to the artistic than the documentarian realm, masterfully capturing a theatrical sense of the unexpected as he offers glimpses into rarefied worlds. He has given us Stephen King as a cross-eyed zombie (1980); Dustin Hoffman as a mischief maker, lounging on a stack of sun loungers at the Beverly Hills Hotel (2004); and Diana Vreeland as an aging Raphaelesque Madonna dressed in a voluminous black gown and sitting cross-legged in her famous red-clad living room at 550 Park Avenue (1979). Becker, a lover of spontaneity who deftly plays with perspectives, keeps us intrigued with his open-ended narratives.

“Looking through a lens — specifically down into the ground glass of a twin-lens Rolleiflex, which reverses the image — has always been a transportive experience, as if I’m observing my own private theater production unfold,” Becker says.

Becker knows more than a little about such productions. His mother, Patricia Birch, was a Martha Graham protégé who segued into a prolific career choreographing on Broadway and in Hollywood. His father is credited with bringing modern European film to American audiences. “I grew up around creative and theatrical people — writers, dancers, actors, directors, producers, singers and so on,” says Becker. “So, these are familiar fields to me.”

And for Becker, life often imitated dramatic art. Case in point: his early-’70s encounter with Salvador Dalí at the St. Regis Hotel, in New York, where the eccentric artist kept a special room as his studio.

Becker had just turned 18 and hadn’t yet started his Harvard course. “I remember taking snapshots of him between a sea of heads. All of sudden, Dalí caught a glimpse of me and pushed his way through the crowd. He grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and led me into another room, where he posed in front of a large painting and instructed me to take his photograph. It was pure theater! I understood that staging a setting doesn’t make a photograph any less real or spontaneous. The authenticity is still as powerful as it is revealing.”

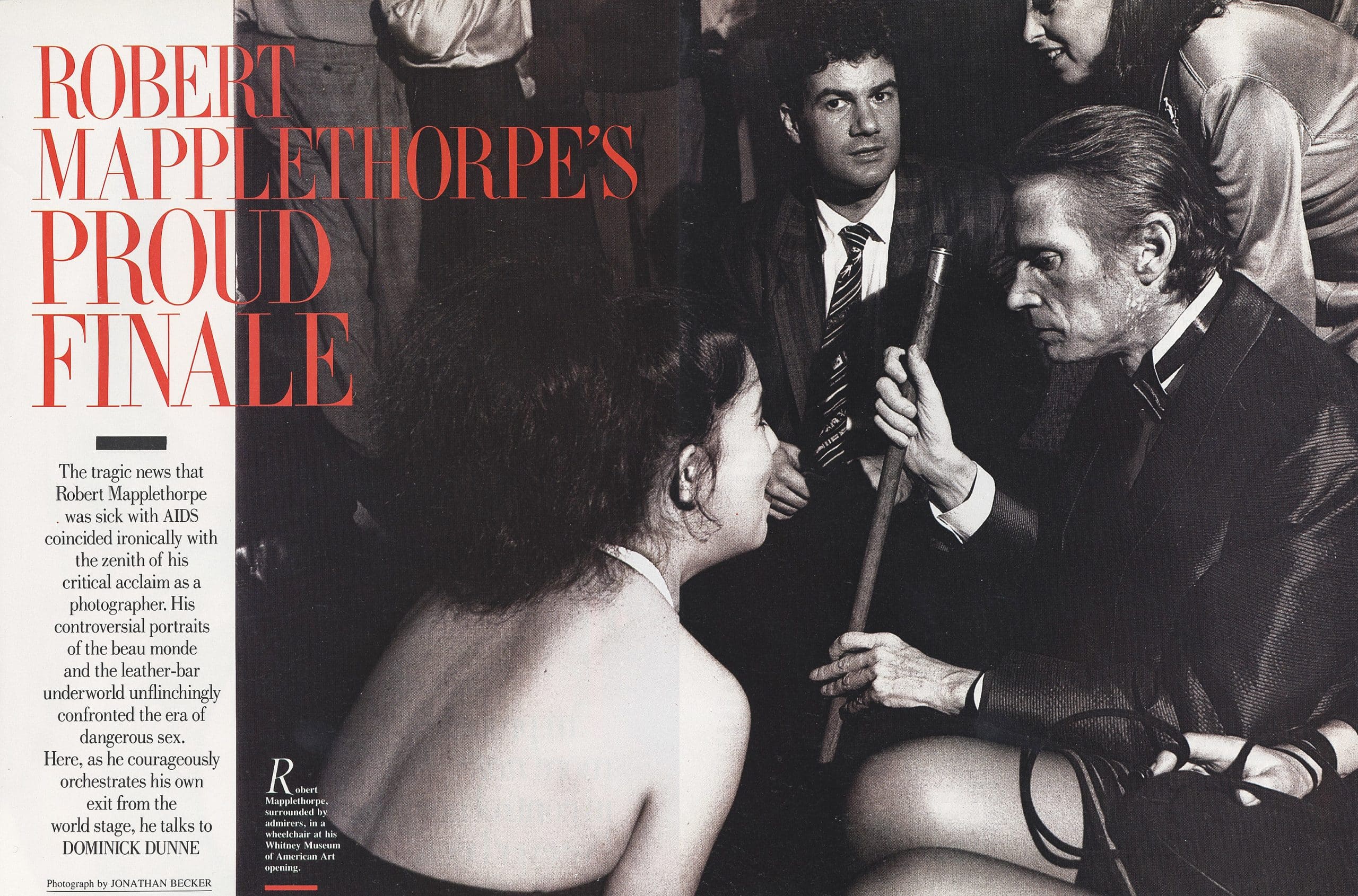

The photographer’s unconventional way of directing his eye is clearly instinctual, resulting in an unusual aesthetic that mixes perception, myth and reality in equal measure. This balance is most apparent in his famous black-and-white picture of Robert Mapplethorpe, taken in 1988 at the opening of Mapplethorpe’s retrospective exhibition at the Whitney, when the famed photographer was dying of AIDS. It is a group shot, showing various figures at different angles, in which Mapplethorpe, caught in profile and listening intently to a woman kneeling beside him, seems to stop time. The moment is heavy with emotion and also dreamlike. It is ineffably surreal.

“While I was too young to quite participate or get really swept up in the nineteen-sixties drug culture, the Dada and Surrealist movements somehow seemed to me to have anticipated all that was happening and in a much more elegant and humorous way,” says Becker.

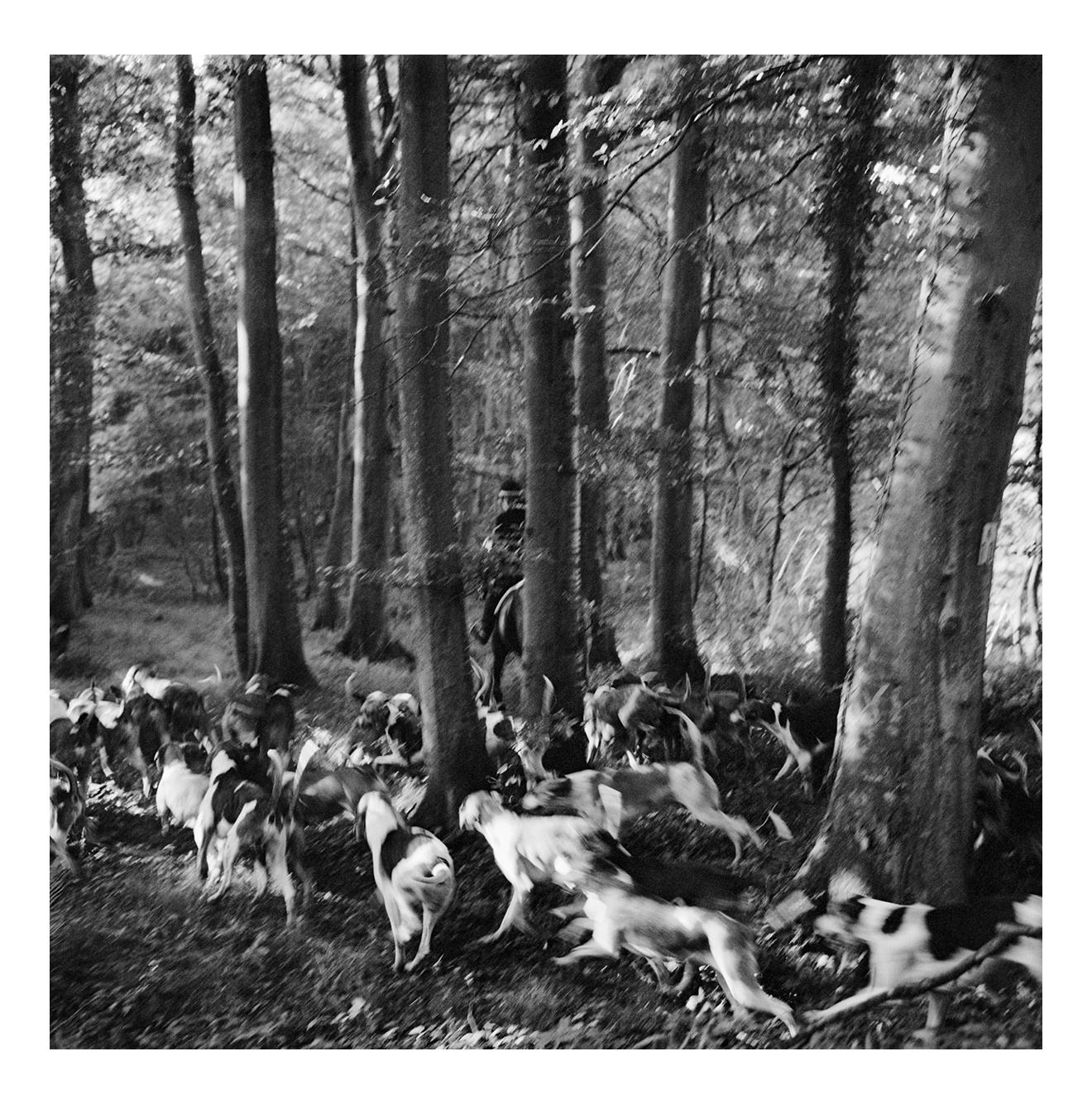

Does he have a favorite photograph that encapsulates this insight? Surprisingly, the image he cites is not a portrait but a landscape shot.

“It’s called La Chasse au Cerf [Deer Hunt, 1975], and it shows dogs running through the woods. I find it very peaceful, even though it’s full of energy. I was just a kid when I took it, but it greatly encouraged me because I saw that the focus and intensity I had applied [to the shot] had somehow recorded itself on film. It is this part of the surrealism of photography that I find so magical.”

It is a sentiment he shares with Brassaï, who famously once declared, “Only powerfully conceived images have the ability to penetrate the memory.” Becker certainly followed his mentor’s prescription, producing uplifting and poignant photographs that form the framework of an unforgettable legacy.