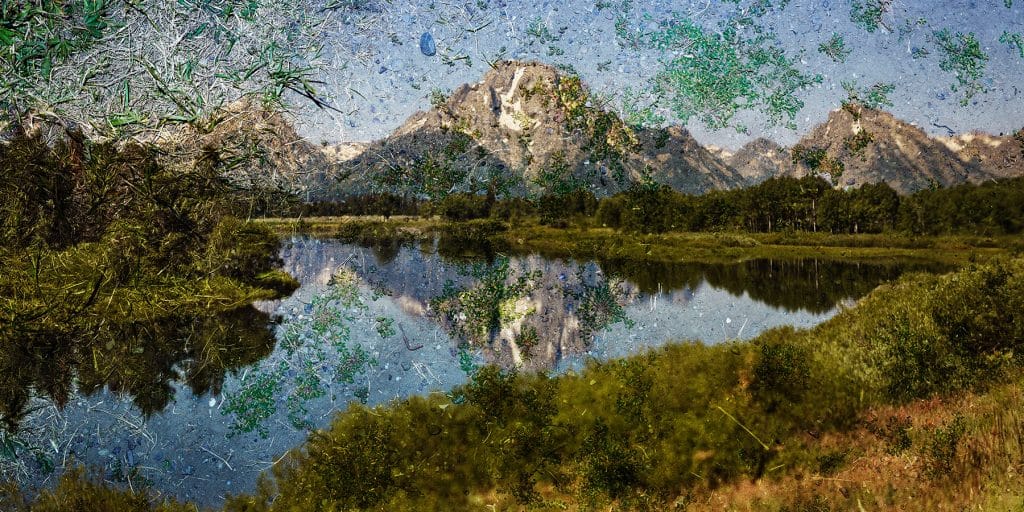

July 29, 2018The creators of photos in the Denver Art Museum’s show “New Territory: Landscape Photography Today” take an unconventional approach to the medium, exemplified here by All Consumed #37, 2017, by Gary Emrich (image courtesy of the artist and Robischon Gallery). Top: Tent Camera Image on Ground: View of Cathedral Rocks from El Capitan Meadow, Yosemite National Park, 2012, by Abelardo Morell (image courtesy of the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery).

People who view Alison Rossiter’s photographs are often reminded of places they’ve been — say, where they used to stargaze in their youth. One picture from her 2014 series “Landscapes, Defender Argo” looks like a straightforward depiction of constellations in a night sky, with the black silhouette of a gently sloping hill in the foreground. But, in fact, the photo isn’t of a real locale.

Rossiter created it by developing long-expired photo paper in her darkroom, exposing just the bottom portion of the paper to light to create the hill. The starry sky comes from mold that had grown on the paper, which dates back to 1911. “Landscapes trigger personal memories,” Rossiter observes. “With a simple action, I created an image that’s universally recognizable.”

Rossiter’s trompe l’oeil print is an example of how a new exhibition at the Denver Art Museum upends traditional notions of landscape photography. “New Territory: Landscape Photography Today” (on view through September 16) contains more than 100 works by 40 contemporary photographers, all of whom depict landscapes in unusual ways, whether by experimenting with traditional darkroom techniques or applying newfangled digital processes to otherwise conventional pictures.

“Questions about the landscape and the environment are foremost in people’s minds right now, and this exhibition is a way to foster discussion,” says Eric Paddock, curator of photography at the museum.

“New Territory” brings together heavy hitters — Edward Burtynsky, Andreas Gursky, John Chiara, Mark Ruwedel — and rising talents, such as François-Xavier Gbré, Valérie Anex and Jennifer Colten. Some explore memory and nostalgia, while others focus on how humans are changing the natural world.

Alison Rossiter’s Landscapes, Defender Argo, expired September 1911, processed 2014. Image courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery

Historically, artists have played a key role in landscape preservation. Early 20th-century photographs provided a powerful argument for the establishment of the U.S. National Park Service a century ago, and iconic national park shots by Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter captured the public’s imagination and fueled conservation efforts.

“Those photos emphasized the parks’ splendiferousness, and they glorified the perfection of the photographic print,” Paddock says.

Contemporary creators appear to be having fun subverting or reinventing those traditions. Abelardo Morell, a Cuban-American artist whose work is internationally renowned, shoots national parks using a tent camera to project onto the ground an image that he then photographs digitally. Viewers see both a vista and the terrain they’d stand on if they were there, creating a certain intimacy.

One of the most wildly experimental artists represented in the exhibition is Los Angeles native Matthew Brandt, whom Paddock deems “the mad scientist of contemporary photography.” Brandt willingly accepts the title, joking that he needs a lab coat and a crazy hairdo. In my studio, he says, “I have algae growing in tubs in the bathroom, and in a corner, I’m making a time-lapse film of mold growth.”

Brandt incorporates natural elements from the sites he photographs in his development process. Lake Isabella CA TC 2, 2014, which is in the exhibition, is a triptych of chromogenic prints that were soaked in water from the lake. The image has faded, and black, purple and green shapes have spontaneously deposited on the paper, making it look more like a painting than a photo.

Brandt has also used Flint, Michigan’s notoriously contaminated water supply to produce photos of the city, and he’s buried prints he made of Hawaiian rain forests in the soil and dug them up later. He created gritty images of Atlanta by mixing silver nitrate with the ingredients for peach pie, and he made pictures of demolished buildings with his own photographic emulsion made, in part, from dust from razing sites.

“We think of a photograph as an immutable representation of a place, but Matthew is calling that into question, suggesting that the photograph isn’t a reliable reminder of our experience,” Paddock says. “As in our memories, things are superimposed, move around or disappear in his photos. They’re intentionally splotchy.”

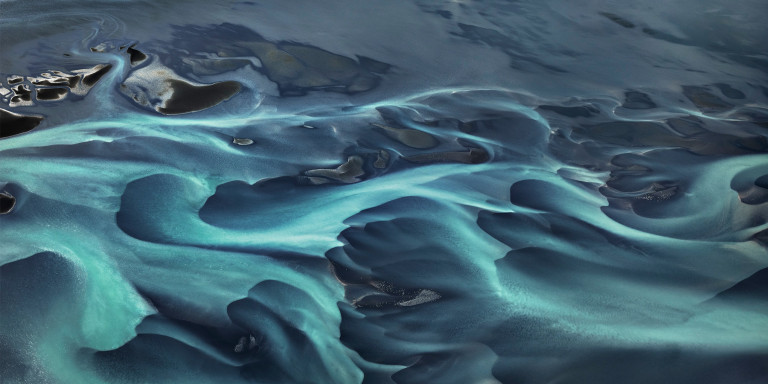

The Lake Project 24, 2002, by David Maisel. Courtesy of David Maisel and Yancey Richardson Gallery/Haines Gallery/Ivorypress Gallery

Unlike Brandt’s, David Maisel’s prints are pristine, although the terrain they capture has been decimated by human activity. His series “The Lake Project,” a photo from which is included in “New Territory,” depicts Owens Lake, which is located east of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California and once measured 200 square miles. Beginning in 1913, water from the lake was diverted to Los Angeles, and it still provides a significant percentage of the city’s supply. As the waterline descended, mineral deposits were exposed and were churned into carcinogenic dust storms. Today, the site is one of the largest sources of particulate-matter pollution in the U.S. The minerals that remain in the lake feed bacterial blooms, creating the brilliant blood reds and deep purples that electrify Maisel’s large-scale photographs.

“It’s an environmental disturbance that’s both awful and quite seductive,” the artist says. “I’m interested in how we’re changing the planet — and unfortunately, I have a lot of material.” Taken from a helicopter, Maisel’s images are meticulously composed, their geometric forms often initially unrecognizable as landscapes.

“Like the other artists in the show, Maisel draws viewers in with a beautiful image, then stuns them with a shocking reveal. “His photographs look like twentieth-century abstract paintings,” Paddock says. “They’re very alluring and attractive, but when you begin to understand what they are, it’s frightening.”