April 25, 2016“Living in the Amsterdam School: Designs for the Interior 1910–1930,” a new show at the Dutch city’s Stedelijk Museum through August 28, celebrates relatively unknown creators of highly expressive furniture and objects in early-20th-century Holland. Top: A 1915–17 wallpaper by Lambertus Zwiers (photo by Gert Jan van Rooij). All photos by Erik and Petra Hesmerg, unless otherwise noted

A century ago, members of the Dutch design movement known as the Amsterdam School made the most intractable-seeming materials curl, crest and loop. Rectilinear brick walls were transformed into undulating waves; hardwood surfaces rippled and coiled.

The movement’s founders — Eduard Cuypers, Michel de Klerk, Johan van der Mey and Piet Kramer — have recently received recognition as architectural pioneers. But less is known about the designers who applied their stylistic notions to furniture, clocks, lamps and other furnishings that were part and parcel of the movement’s vision.

“Living in the Amsterdam School: Designs for the Interior 1910–1930,” an exhibition of some 500 design pieces at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam through August 28, aims to explore this forgotten aspect of the movement while bringing visitors into those designers’ interiors.

“There have been many research projects about the architecture and the sculpture of the Amsterdam School, but nobody really researched the furniture of the period,” says Ingeborg de Roode, the Stedelijk’s curator of industrial design, who conceived the exhibition about 10 years ago. “It was always a small chapter at the end of the book, but it was never really researched.”

Over the past decade, the Stedelijk slowly amassed about 5,000 pieces of documentation on furniture, stained glass, lamps and other home accessories. This resulted in a deep understanding of work not just by sculptors such as Hildo Krop and furniture designers Harry Dreesen and Louis Deen but also by stained-glass designers like Willem Bogtman and a surprising number of female designers, not least among them illustrator and typographer Tine Baanders and artist and graphic designer Fré Cohen.

The Amsterdam School, which coincided with early modernism, was dominated by two styles: one influenced by German expressionism, “with undulating forms and ornate details,” says de Roode, and the other a homegrown “more severe geometric style” that referenced the clean, functional minimalism of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie School.

De Honsel, Loosduinen, handled the manufacture of this kaleidoscopic ceiling lamp, 1920–23, which was designed by either Hendrik Cornelis Herens or Frits Woltjes.

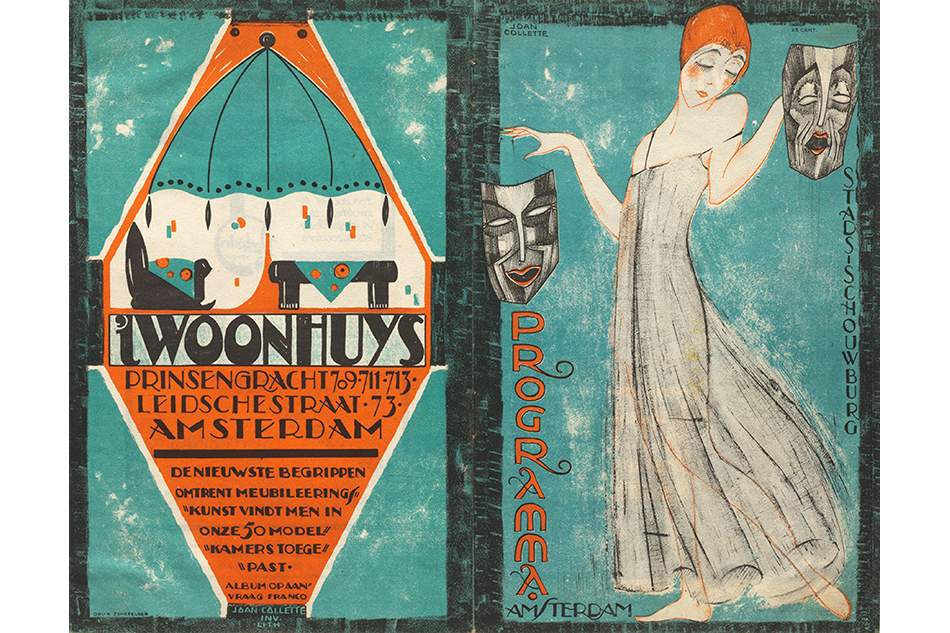

The movement also appropriated international design elements, such as Japanese masks, Austrian graphic design, Indonesian dwellings and other influences, mixing them all together in unusual combinations. For instance, as Frans van Burkom writes in the exhibition catalogue, de Klerk made a table clock that combined a face with a long tongue wearing a Javanese-style headdress and ebony toboggan runners that may have been inspired by Scandinavian peasant art. Like the Dutch populace in those days, the Amsterdam School was known for its open-mindedness.

With the rise in the Netherlands of the De Stijl movement, championed by Piet Mondrian and emphasizing simple graphic elements, primary colors and cool rationality, the Amsterdam School’s playful ornateness fell out of favor, and by 1930 the movement had more or less ended, says de Roode.

Now, a century after the group’s inception, the design objects its members created have become quite collectible, sold by a handful of dealers in the Netherlands, including Galerie Frans Leidelmeijer, Kunstconsult (Art Consult) and Amsterdam Modernism. De Roode feels the work is relevant now because collectors are more interested cross-cultural influences in design and are more fluid about their aesthetics. “We talk a lot nowadays about globalism versus localism,” she says, and “that’s what you really see in this Amsterdam School movement. It was in fact a very local movement, but it took influences from all over the globe.”