December 21, 2015Renzo Mongiardino at his home in Milan, which also served as an office and workshop. Paintings, drawings and samples always covered the walls of his office (photo © Antoine Bootz). Top: Mongiardino enlarged the original entrance corridor of the Mondadori residence in Milan to create a dual gallery and library space, which he adorned with faux marquetry (photo by Guido Taroni, courtesy of Cabana magazine).

At Introspective, we showcase men and women with extraordinary design talent and vision, and one of our latest favorites is the captivating Martina Mondadori Sartogo, the originator of the beguiling interiors journal Cabana — as well as a host of other trend-setting ventures — with whom 1stdibs is hosting through December 31 the Casa Cabana holiday pop-up of stylish and rare artisan-fashioned home furnishings and jewelry. When we first interviewed her, last April, about her highly evocative publication, she mentioned that a major inspiration for the periodical, as well her own thinking about interiors and design, was Renzo Mongiardino, a great friend of her mother’s, who assembled the famously handsome rooms, layered in pattern and rich in whimsy and sentiment, of her family’s Milan residence.

Several photographs of that home were featured in Cabana’s debut issue, and reproductions of a velvet ottoman Mongiardino designed for it are among the offerings of the 1stdibs pop-up shop, as is a Dedar wallpaper based on a vintage screen her parents bought at a flea market in California in the 1970s, which Mongiardino turned into a cupboard for the hall leading into their dining room.

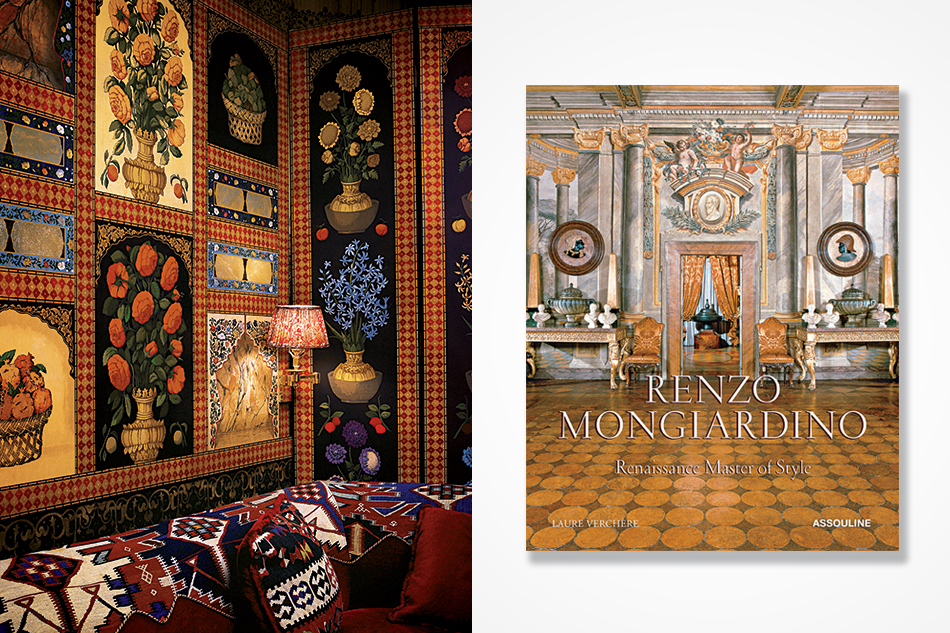

Renzo Mongiardino, who was born in Genoa and grew up in a palazzo, was perhaps the greatest crafter and most inventive conjurer of splendid homes in the second half of the 20th century. (He died in Milan in 1998, at the age of 81.) Mongiardino detested the title “decorator,” preferring “creator of ambience.” Striving to explain the distinctive magic this maestro wrought, admirers often note that, in addition to being an architect, he was also an acclaimed set designer, who worked on both the opera stage and in film and was nominated for two Academy Awards for productions directed by Franco Zeffirelli: The Taming of the Shrew (1967) and Brother Son, Sister Moon (1972).

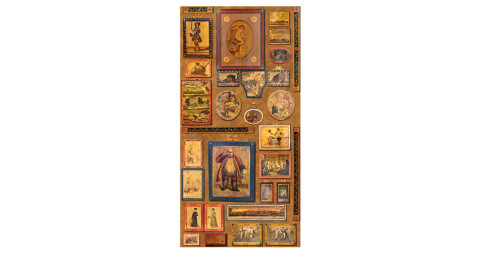

In Mongiardino’s home, his fascination with Turkish exotica, faux finishes and richly toned and patterned textiles was very much apparent. The framed works on the wall were part of his collection of miniature Neapolitan altarpieces from the 18th and 19th centuries, exquisite creations tellingly made out of “poor materials.” Photo by Oberto Gili

Certainly, he brought his skills in creating illusions and visual drama to his residential projects. The practice of employing scale models, so common among scenic designers, was central to his interior design process, but he took it further, making a series of detailed models of various scales — first for himself, then for clients, then contractors. To Mongiardino, the models were essential, allowing him to fully grasp the dynamics of a space — proportional relations along with circulation and the play of light throughout the day and evening. Once the room was understood, the decor could be developed “in harmony with the architecture,” in order to “correct its defects, apportion its effects, and create illusions,” as Mongiardino explained in his revealingly named and quite learned monograph Roomscapes: The Decorative Architecture of Renzo Mongiardino (Rizzoli, 1993).

Thus, more than creating fabulous backdrops for fabulous clients — and more on them in a moment — through his singular design wizardry, Mongiardino was fashioning domestic characters, intimate companions of a sort, with and in whom his clients could dwell. One’s home is a “choice in life,” he stated in his book, “a citadel — agreeable and unarmed, but equipped to deter those who are not welcome and embrace those who are friends.”

Lee Radziwill, photographed in 1966 by Cecil Beaton with her daughter, Tina, could find no designer able to bring intimacy to what she called the “bowling alley” proportions of her London living room until she discovered Mongiardino. He took two different inexpensive Indian fabrics, cut them into panels and alternated them in gilded rod frames, thus starting a trend for “Indian rooms.” Photo courtesy of the Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

The clients who sought these citadels were not only some of the world’s wealthiest individuals but also the most cultivated. Their ranks included Countess Cristina Brandolini d’Adda, who was his first client; Italian aristocrat Marella Agnelli; Princess Firyal of Jordan; Elsa Peretti; Lee Radziwill and her sister, Jackie Onassis; Marie-Hélène Rothschild; Valentino; Gianni Versace; and Jil Sander (the minimalist fashion designer was his last, and perhaps most unlikely, client). As they were people of extraordinary taste, Mongiardino encouraged his clients’ input, using his dioramas to communicate his ideas and better demonstrate their own contributions. “Sometimes, debate or even dispute leads to better results,” he counseled, noting that the most beautiful and original architecture in Italy often arose out of “polemical collaboration.”

Mondadori Sartogo, who is acquainted with a number of Mongiardino’s clients, confirms that they got along with him wonderfully. “He started every project by asking, ‘What is your favorite color palette, and what do you collect?’ ” she says. Mongiardino knew that consummate collectors were usually more interested in dramatically showcasing their treasures than in their home’s architecture, so understanding their passions was critical to the formation of a decorative scheme. A case in point was his design of the sumptuous Paris residence in the Hôtel Lambert of Guy and Marie-Hélène de Rothschild. Figuring out how to display the Rothschilds’ voluminous collections of art and objets was the greatest challenge of his career, Mongiardino once confided to Mondadori Sartogo’s mother. Arguably, it was his greatest triumph, as well.

“The house . . . is a choice in life, a citadel — agreeable and unarmed, but equipped to deter those who are not welcome and embrace those who are friends.”

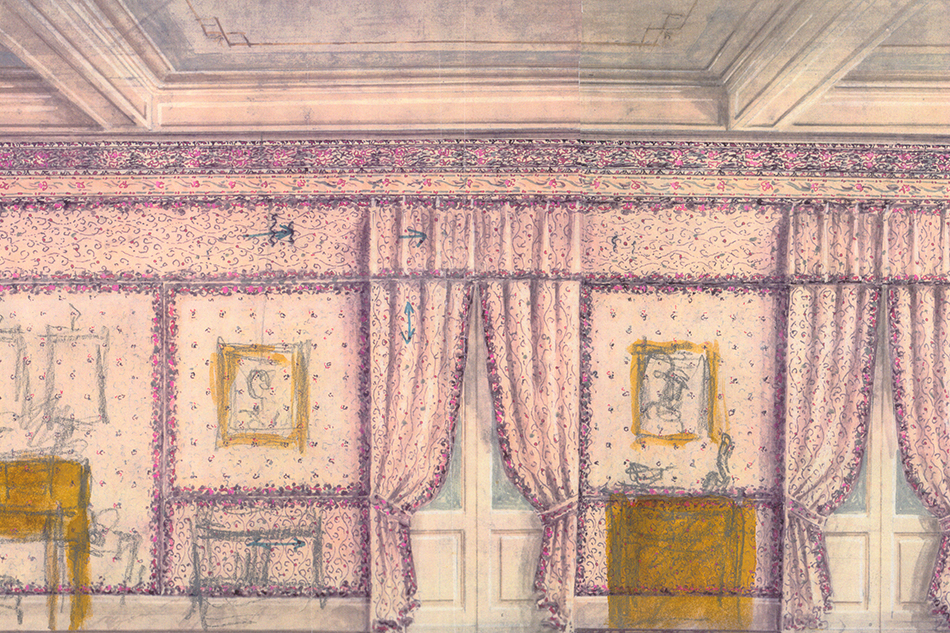

When developing a decorative scheme for Villa Frescot, the Agnelli residence outside Turin, Marella Agnelli, encouraged by Mongiardino, researched antique Piedmontese fabrics and then designed her own, which were specially made for use throughout the house. Photo by Oberto Gili

The tremendous attention that Mongiardino devoted to learning about his clients’ lives, combined with his own erudition in all matters of style, made him a compelling, even empowering, figure. “I learned more from Renzo than anyone else I can think of. I miss him terribly,” declared Radziwill, one of the first people outside Italy to seek his design expertise, in the sumptuous 2013 monograph Renzo Mongiardino, Renaissance Master of Style (Assouline). During his first collaboration with Marella Agnelli on the Villa Frescot, outside Turin, he encouraged the Italian aristocrat, who had trained as an artist, to design fabrics for the rooms based on old Piedmontese prints she had been researching. When Gustav Zumsteg, the Swiss haute-couture fabrics manufacturer, came for a visit, he was so impressed with Agnelli’s creations that he gave her a contract to design fabrics for him, which, she concedes in Marella Agnelli: The Last Swan (Rizzoli), “gave me a sense of purpose.”

Much is made of the romantic byzantine opulence of so many of Mongiardino’s interiors: the layers of patterns, the jeweled tones, the quantities of Persian rugs, the wall paneling of intarsia and Cordovan leather, the surfeit of marbled and mosaic surfaces. (What few realized, though Mongiardino never hid, was that many of these rich materials were faux. The sumptuous Cordovan leather walls of an industrialist’s English country estate, for instance, were actually cardboard skillfully painted and aged. This was part of Mongiardino’s impressive stagecraft; what interested him always was the effect, the atmosphere.)

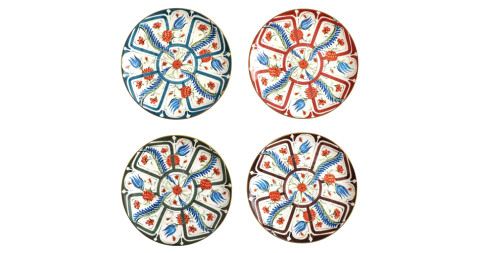

“Turkish, Islamic design was a great influence on him, as was India, although he never traveled there,” says Mondadori Sartogo. In truth, he stole ideas with a magpie’s avidity from everywhere: A pretty motif on an 18th-century Sèvres teacup became part of the design on porcelain wall tiles for a morning room in the South of France; the decoration on a 19th-century porcelain-and-bronze clock was reinterpreted in the painted adornments on the walls of a luminous formal dining room, which were treated with special finishes to imitate the gloss of the bisque clock face.

With its gothic drama, Mongiardino’s sitting room seems suitable as a set for Verdi’s La Traviata. When the contents of his home were put up for auction, his friend, the novelist Umberto Pasti, wrote in the catalogue that, for all their glamour, his rooms possessed “the corrosive breath of melancholy.” Photo by Oberto Gili

But perhaps the greatest influence on Mongiardino’s decorative vision was the Italian Renaissance and Italy itself. Roomscapes is full of references to Renaissance masters, as well as to Italian buildings and towns. While he deftly transformed these decorative citations and techniques into highly original elements, it seems fitting that in his later years, he affected a fanlike gray beard that gave him the look of a classics professor. Far from being a rumpled, tweedy figure, he was always exquisitely dressed and cut an elegant figure. Yet his beard did seem to symbolize the increasing consequence he attributed to himself and to his work as his commissions grew ever grander. This development saddened Radziwill, who commented in a reminiscence about him in T magazine that she preferred the more relaxed man she had known earlier in his career, in the mid-1960s, when the two had to fumble with French to communicate, as she knew little Italian and he no English.

Whatever the degree of his gravity, Mongiardino was an enthusiastic believer in the importance of collaboration. His studio was small, and he depended for his interiors and stage and screen work on a devoted extended family of craftspeople — model makers, carpenters, painters, gilders, faux finishers . One of his favorites was Lila de Nobili, a celebrated fashion illustrator and acclaimed stage and costume designer in her own right. In the T magazine article, Radziwill recalled that for the dining room of her house in the English countryside, Mongiardino covered the walls in pieces of tan-colored Sicilian peasant scarves and then had de Nobili adorn them with paintings of vines and pictures of Radziwill’s two small children before lacquering the surfaces for an antique effect. So that the pale draperies in the room wouldn’t appear new, they were dipped in tea.

Martina Mondadori Sartogo, at right, sits on a Mongiardino-designed pouf in her parents’ home with her friend Ginevra Elkann, the granddaughter of Marella Agnelli, one of Mongiardino’s greatest patrons.

Why was Mongiardino so obsessed with the past? When he graduated with an architectural degree from the Politecnico di Milano, in 1942, practitioners of his generation and the one preceding were still grappling with what Italian modernity should be. Like many of this group, he looked back into history to find Italian motifs and approaches that could be freshly interpreted for the new age of industry. Although a committed modernist, Giò Ponti, one of Mongiardino’s professors at the Politecnico, was doing the same, although to different ends. Consider especially Ponti’s stylish collaborations with Piero Fornasetti, another Italian designer creating original work from antique inspirations.

So Mongiardino’s continued fascination with the past was not as reactionary or eccentric as it may seem today, but rather deeply Italian. In Roomscapes, he observed that Greek and Roman elements have been continually reinvented over the centuries, proof, he felt, that “revivals never end.”

The son of the man who introduced color television to Italy, Mongiardino was far from being a Luddite. He embraced and admired many modern conveniences. But he believed that in contrast to new inventions like televisions and airplanes, living spaces were elemental. To change a home’s form, he wrote, “is more a yearning desire for the new than a functional requirement.”

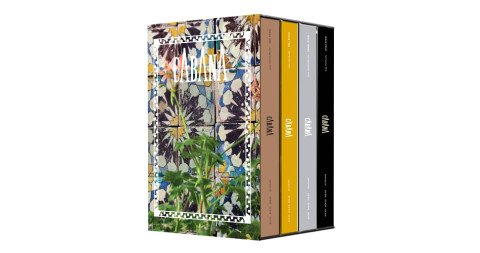

Even in this age of the Internet of Things, there’s still some truth to that. The passionate following that the atmospheric, at once arcane and topical, gorgeously printed Cabana has engendered in its two years of existence is evidence that Mongiardino’s decorative vision may very well be on the verge of a revival.

Shop Mongiardino-inspired items from Cabana

Shop the Casa Cabana pop-up on 1stdibs, only through December 31