December 11, 2017Rizzoli recently published Cabana magazine founder Martina Mondadori Sartogo‘s volume on 20th-century Italian maximalist and society decorator Renzo Mongiardino. The style- and jetsetter grew up in a home that Mongiardino designed for her parents.

The acclaimed Italian architect and interior designer Renzo Mongiardino (1916–98) never shied from juxtaposing a flocked wallpaper with a dozen other patterns in a dimly lit room. He’s the subject of a new book from the trendsetters at Cabana magazine and the particular project of its founder, Martina Mondadori Sartogo, who grew up in a Mongiardino-designed home. The Interiors and Architecture of Renzo Mongiardino: A Painterly Vision (Rizzoli) offers supersaturated photographs by Guido Taroni of 20 projects, most in Italy, and the mysteriousness of each image makes you want to step inside it to discover more.

Sartogo’s considerable clout in the social and design spheres (she moves largely between Milan and London and travels to various stylish points in between and beyond) has resulted in big “gets” in the book. Lee Radziwill, who commissioned Mongiardino for her London home, notes that “no one today matches his taste,” and Tiffany designer Elsa Peretti talks about how she misses him personally. There’s something improbably tasteful in all the rooms, no matter how incredibly maximalist Mongiardino made them; it’s hard to imagine someone else working as well with marquetry, marble and wildly colored ceramic tiles. You don’t necessarily have to be Italian to pull it all off but — well, actually, you do.

Purchase This Book

or support your local bookstore

Architect and committed classicist Peter Pennoyer worked with his frequent book collaborator, writer Anne Walker, on a new Monacelli Press volume devoted to the grand country-house stylings of early-2oth-century designer Harrie T. Lindeberg.

Certainly, no one is better qualified to write about historic country houses than architect Peter Pennoyer, a prodigious designer of homes inspired by these stately residences and a master restorer of many original examples. Last year, he did a whole book about his own Millbrook, New York, home, and he has authored monographs on such Gilded Age architects as Delano & Aldrich and Grosvenor Atterbury. Now, with his frequent writing collaborator, the architectural historian Anne Walker, he has come out with Harrie T. Lindeberg and the American Country House (Monacelli Press). No less a pooh-bah than Robert A.M. Stern says in his introduction that Lindeberg (1879–1959) “brilliantly synthesized” previous architectural traditions.

Lindeberg’s clients had names like Doubleday and DuPont — and they all owned spreads that really spread. Although often compared to the British architect Sir Edward Lutyens, he had his own grand style. The ceilings and roofs are particularly noteworthy: The dramatic pitch of slate that tops a Lily Pond Lane affair in New York’s East Hampton holds your eye, as does the dining-room ceiling in a Lake Forest, Illinois, country club that somehow marries a cathedral and a barn. It’s interesting to see Lindeberg begin to engage with the Art Deco style right as the Depression snuffed out the demand for palatial escapes. Which might make you think: Build that country house now, while you still can.

Purchase This Book

or support your local bookstore

Contemporary French decorator extraordinaire Joseph Dirand has released his first monograph, published by Rizzoli and called, simply, Interior — a title even more minimalist than his strictly modern, clean-lined designs.

The heavy paper stock and matte finish of Joseph Dirand: Interior (Rizzoli) slightly soften the hard edges of the Paris-based designer’s work; he is, as Architectural Digest has put it, a “strict modernist.”

The book’s black-and-white images read as almost purely abstract, melting into gauzy shapes. The gorgeous photos are by his brother, Adrien Dirand, who contributes as well a touching reminiscence on their childhood. (Their father, Jacques, was also a noted photographer.)

Largely working in New York and Paris, Dirand has set a high bar for spare and luxurious spaces. The texts, too, are suggestive rather than info laden: Yann Siliec introduces each project ever so briefly, and the captions, offloaded to the back so as not to interfere with the look, are themselves minimal (a touch more info would have been welcome).

Design scribe Sarah Medford contributes an afterword that emphasizes Dirand’s storytelling abilities and the fact that clients can’t help but give him free rein. Based on this book, you would too.

Purchase This Book

or support your local bookstore

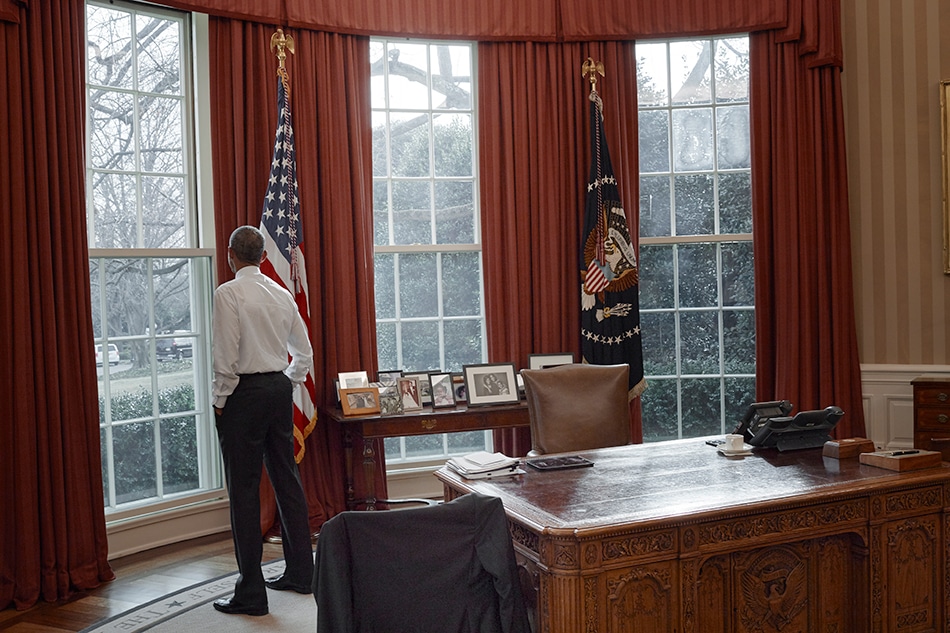

Despite the book’s title, the works collected in Annie Leibovitz: Portraits 2005–2016 (Phaidon) are just as focused on the design and decor of the locations where the famed photographer shoots her subjects as they are on the subjects themselves.

When Annie Leibovitz began thinking about her latest monograph, she knew what she wanted it to end with: a photo of Hillary Clinton in the White House. And as she writes in the newly released Annie Leibovitz: Portraits 2005–2016 (Phaidon), what she would have focused on in the picture wouldn’t have been Clinton herself but the setting. “I spent a lot of time imagining which desk Hillary would choose,” she notes in the afterword. “Was one of Eleanor Roosevelt’s desks available?”

We’ll never know which Clinton would have selected, but thanks to this tome, we do know a lot about the decoration and decor that surrounds many other powerful women (and men). A shot of Queen Elizabeth II in a brocade gown also includes an ornate side cabinet, a chandelier and a rug that reign as resolutely as the British monarch herself. Sophia Loren, meanwhile, commands a Geneva apartment whose wall tapestries, plush upholstery and silver-framed photos displayed on a pair of console tables seem to embrace the actress as tightly as her form-fitting gown. Anna Wintour’s home is as chic as her attire; the settee, the small round table, the pottery on the mantel and especially the abstract painting on the wall establish her tastemaker cred.

Clearly, this volume isn’t just about people but also about people’s relationship to their environments, and it shows that Leibovitz is as much a photographer of architecture and interiors as she is a portraitist. “Location is an integral part of a picture,” she writes. “The history of a place, its sights and sounds, influences a picture.” Indeed, the book offers one compelling backdrop after another. In 2013, Michael Bloomberg posed in his City Hall office: not a room but a bullpen, in which the high-powered New York mayor looks like just another worker ant. And in a shot of Jeff Koons — never mind that Koons is stark naked — the space he’s in, seemingly a home gym, commands attention. Why is there no art on the walls? And no shades on the windows? Are neighbors allowed to peep at Koons but not at Koons’s work? — FRED A. BERNSTEIN

Purchase This Book

or support your local bookstore

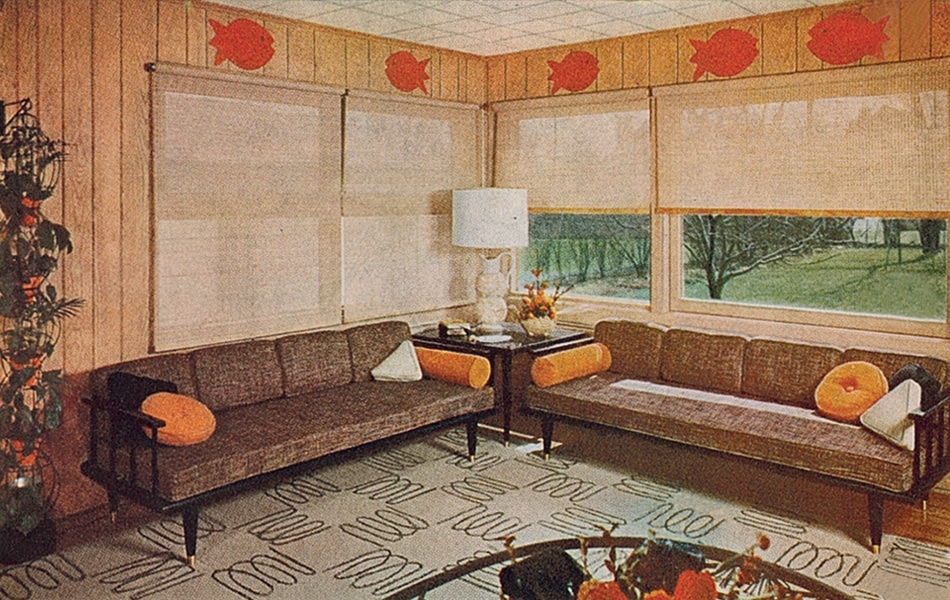

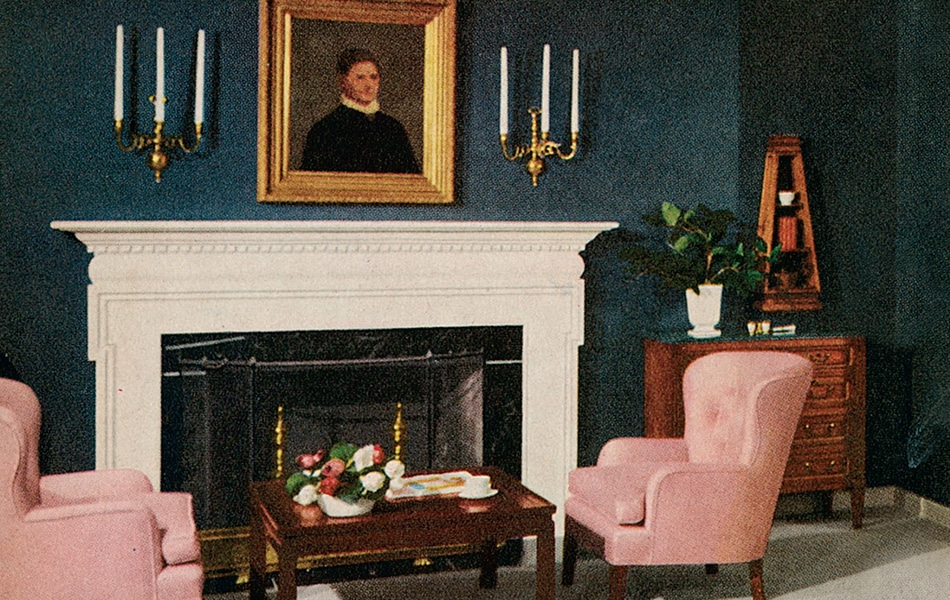

The Better Homes and Gardens Decorating Book (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) is a page-for-page rerelease of a 1961 original. It opens, charmingly, with the greeting “Dear Homemaker.”

Let’s turn the clock back to 1961. As President John F. Kennedy was settling into his job, that year’s edition of The Better Homes and Gardens Decorating Book was published. Now it’s been rereleased by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt as a facsimile.

It might feel like a goof gift at first, since the reader will be thinking, “We were so innocent then.” “Paint changes a room” states one piece of display type. You don’t say!

But once you get past the slightly yellowed images, you realize, “Hey, that upholstered daybed is pretty kicky, and good to remember that my decorator did not invent mixing traditional and modern furniture.”

With its blend of time-capsule enjoyment and actual advice (check out the chapter on electrical wiring, something you wouldn’t see today), it might be the most thumbed-through book on your coffee table come January.

Purchase This Book

or support your local bookstore

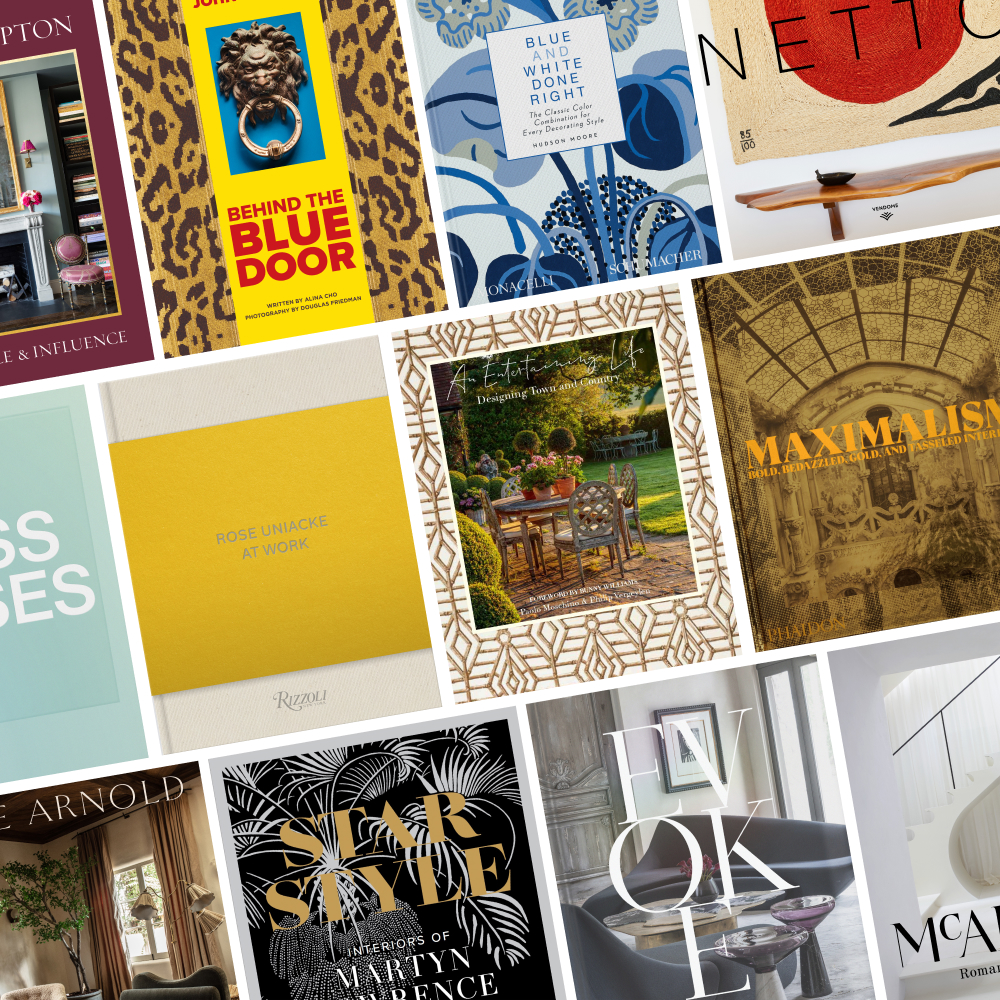

This volume from the Vendome Press offers a rare glimpse inside some of the most impressive apartments in all of New York City, from a Fifth Avenue classic by McKim, Mead & White to the modern marvel of Rafael Viñoly’s 432 Park.

For a certain subset of people who treasure floor plans, Life at the Top: New York’s Most Exceptional Apartment Buildings (Vendome) will be like a bowl of candy. At 1 Sutton Place South — originally designed by Cross & Cross and Rosario Candela for Amy Phipps, daughter of Pittsburgh steel magnate Henry — the wingspan of the penthouse is mind-boggling, especially given that the entire perimeter is surrounded by a terrace; at the Renaissance-style 998 Fifth Avenue, designed by McKim, Mead & White for the great developer James T. Lee, the same can be said of the number of maid’s rooms (nine!). Authors Kirk Henckels, the vice chairman of the real estate agency Stribling & Associates, and the prolific Anne Walker have created a book that will fuel the ongoing conversations about which building is the best of the best — fantasy baseball, but for residential real estate.

Michel Arnaud has taken well-composed photographs of present-day apartments in each of the buildings, and there are also historical images of many. Although the 1920s represented the high-water mark of such luxury construction, this book takes us into the 21st century, featuring Robert A.M. Stern’s 15 Central Park West and Rafael Viñoly’s 432 Park, the tallest residential structure in the Western Hemisphere. Comparing the ornate woodwork of the first entry in the book — the Upper West Side’s Dakota, designed by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh in 1884 — to the massive floor-to-ceiling-windows at 432 Park may seem like mixing gilded apples and gilded oranges. But as our authors remind us, “In matters of taste, there can be no dispute.”

Purchase This Book

or support your local bookstore