March 17, 2019The American Kennel Club Museum of the Dog opened its new Midtown Manhattan space in February, showing off hundreds of works from its vast holdings of canine art and artifacts. Top: Edwin Megargee’s 1937 oil-on-canvas portrait of champion poodles Bonnie Brighteyes of Mannerhead and Arnim of Pip. All photos ©David Woo, courtesy of AKC, unless otherwise noted

Perhaps the most famous dogs whose likenesses are displayed at the museum are Scottish terriers Barney and Miss Beazley, who occupied the White House during the presidency of George W. Bush and pose here in a 2005 painting by Constance Coleman.

A new museum is almost always noteworthy. But a new dog museum? As a canine lover of nearly five decades’ standing, I rushed right over to see the Museum of the Dog, which opened last month in New York. Created by the American Kennel Club (est. 1884), the folks who bring you the Westminster Dog Show, it has on display some 300 works, a small part of a 1,700-piece trove the institution calls one of the world’s largest canine-art collections — and is anyone going to challenge them on that?

This New York debut is actually a triumphant return of sorts: From 1982 to 1987, an iteration of the museum existed in the same Manhattan building where the AKC had its headquarters. Now, the museum and HQ are together again, in the Kalikow Building, just below Grand Central Station on Park Avenue South.

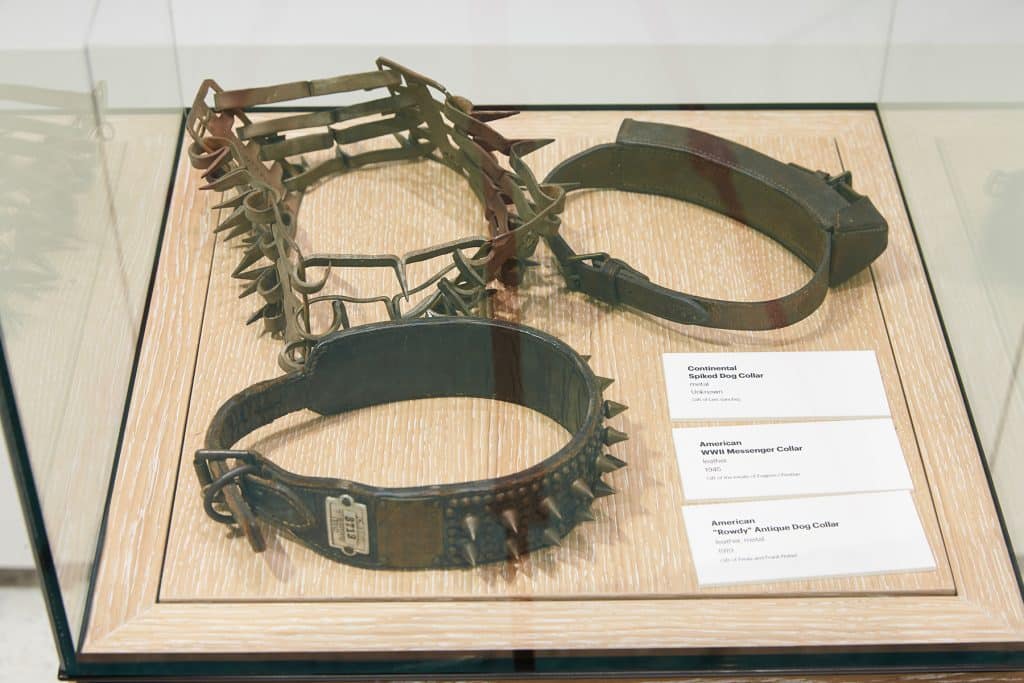

The collection, displayed over two floors connected by an airy double-height atrium sporting a dramatic floating staircase, is composed largely of realistic paintings in which dogs are the primary subject. These loving portraits, with titles like Pointer Pointing at Quail and West Highland Terrier in a Landscape, keep company with ceramic sculptures and some photographs.

“Of all animals, the dog has had the closest bond to humans over the centuries,” says Alan Fausel, the AKC’s executive director and alpha canid in terms of getting the museum up and running. “The museum puts that into focus.”

Beyond the AKC’s institution, dogs can be seen at museums, galleries and fairs around the country. Wayne Thiebaud’s Beach Dogs (2004–10) was recently on view at Acquavella Galleries‘ booth at Frieze Los Angeles.

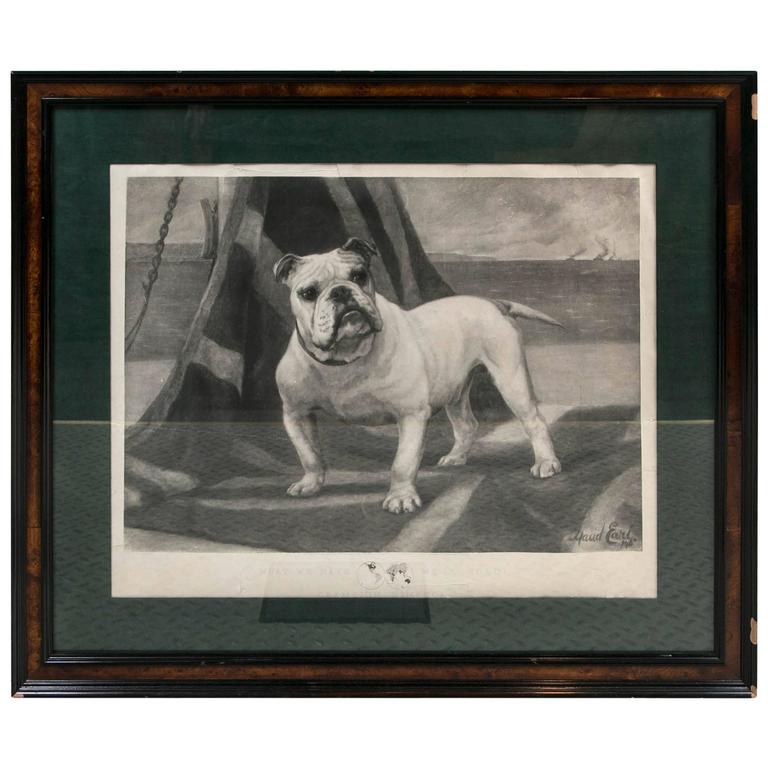

Some of the big-name artists on hand are Sir Edwin Landseer, the 19th-century British painter who made his name with dog and horse pictures; the British-American canine chronicler Maud Earl; and the contemporary artist William Wegman, he of Weimaraner portraiture fame. But perhaps the most famous subjects are the dogs belonging to two different President Bushes: Millie, the English springer spaniel who lived with Bush 41, and Barney and Miss Beazley, the Scottish terriers who called the White House home when Bush 43 was in residence.

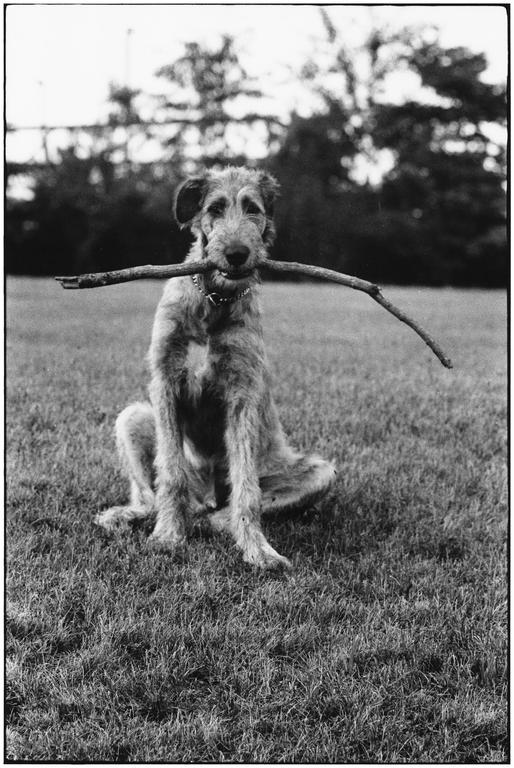

One thing you learn quickly when looking at these hound images: It’s all in the eyes. Renderings of shiny coats are well and good, but the more sympathetic, and anthropomorphic, the eyes are, the stronger the hold on the viewer. Cuteness abounds, too, of course. Good luck resisting Orphans, an 1892 painting by Frank Calderon of a wolfhound nobly protecting two puppies.

Although engineered — and successfully so — to be crowd pleasing, the museum has more on its mind that simply eliciting reactions of “Awww.” Part of the AKC’s mission is to educate the public on the different dog breeds the Club recognizes, and working closely with Gensler, the architecture firm that designed the museum and its exhibitions, it developed some entertainingly interactive features.

The “Find Your Match” kiosk, near the entrance, takes your photograph and immediately tells you what dog breed you’d be. (In case you’re wondering, I’m a miniature pinscher, and trying not to take offense.) In the “Train a Dog on the Job” interaction, you can teach a computer-generated Lab named Molly to sit, stay and roll over. This is part of a larger display called “Dogs on the Job,” which chronicles the history of dogs at work and how they are employed in numerous modern activities.

The exhibitions at the AKC museum draw from a collection of some 1,700 works, most of which date to the 19th and 20th centuries.

Packs of people have been making their way to the museum since the opening, with the 4,000-volume nonlending library on the second floor proving a major attraction — much to Fausel’s amazement. “It’s been full, particularly with children,” he says.

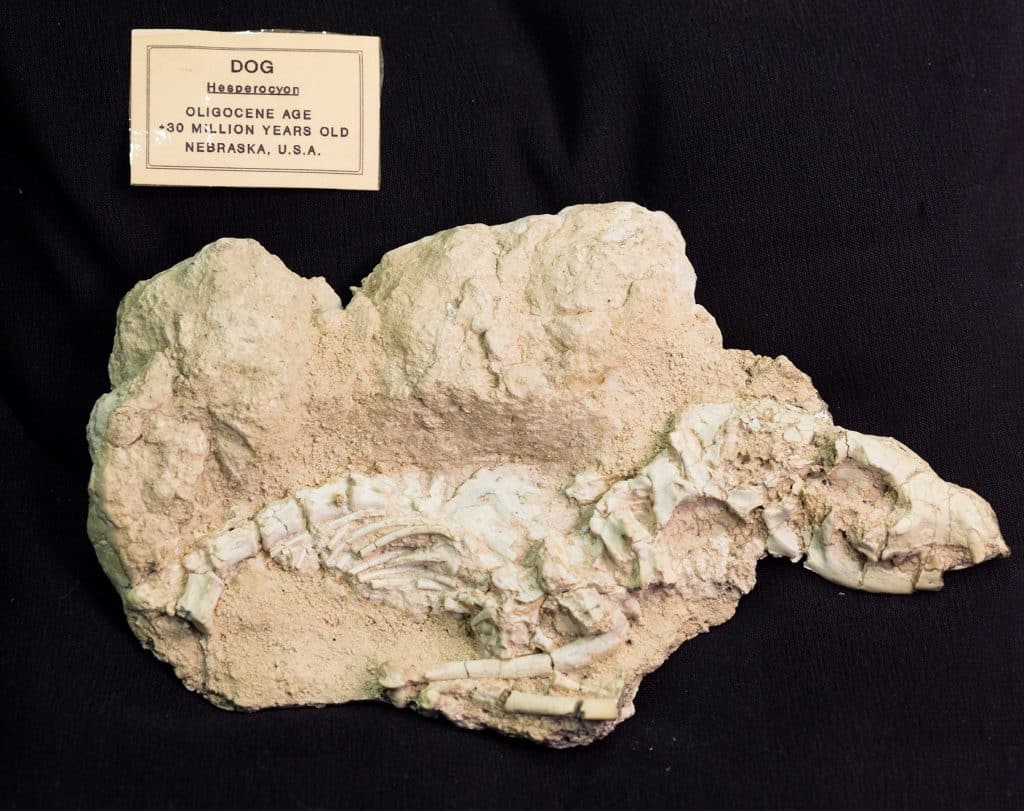

Most of the items in the museum are from the 19th and 20th centuries, and some are of only middling quality. But, of course, dogs in art go way, way back. “There have been canine depictions since ancient times,” says Fausel. Although he doesn’t have any millennia-old works in his trove, it takes only a few stops on the 4/5/6 subway line to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to prove his point.

Currently on view there is a Mesopotamian ceramic figure, from more than 3,000 years ago, of a mastiff in mid-snarl with traces of the original paint job still visible, though missing its limbs in the way of many ancient statues. This relic of the Kassite culture may have served as a guardian or healing figure. (A sop to cat lovers: The Met has even more depictions of felines, all told, than canines. These include an ancient Egyptian bronze statuette intended to hold a mummified kitty and Alberto Giacometti’s fantastically attenuated The Cat from 1954. You can see both anytime.)

A visit to the Met reveals that in many depictions throughout history — unlike in most of those encountered at the Museum of the Dog — our furry friends have been the beta to the human alpha, pictorially speaking. The Met is currently displaying the Anthony van Dyck portrait James Stuart, Duke of Richmond and Lennox (ca. 1633–35), which shows the nobleman nuzzled by his faithful hound, a gesture that was intended to reflect well on the man and that became a trope employed constantly for centuries after.

Fausel notes that the Victorian era, with its mania for classification, helped spur interest in specific breeds, which were then codified and idealized in portrait form. This development allowed dogs to take on more of a starring role.

In Thomas Eakins’s The Artist’s Wife and His Setter Dog (ca. 1884–89), at the Met, the pooch gets equal billing, if no name. My favorite part of this cozy interior scene is that Mrs. Eakins and the setter have the same appearance of utter repose and relaxation, and both are looking right at the painter — and at us, the viewers.

Visitors to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art can enjoy the quiet charms of Thomas Eakins’s The Artist’s Wife and His Setter Dog (ca. 1884–89).

Once you start thinking about dogs in art, of course, they appear everywhere. On a recent trip to Los Angeles, I came across, at the Hammer Museum, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Touc, Seated on a Table, an adorable bulldog portrait found in the Armand Hammer Collection and also available on a coffee mug in the gift shop. And the next day, at the Frieze Los Angeles art fair, there was Wayne Thiebaud’s Beach Dogs (2004–10), a scene of canine frolic, in the booth of Acquavella Galleries.

Personally, I have always been a fan of working dogs, those tireless sled pullers and cattle herders. And to me, it’s most compelling when a dog performs a surprising role in an artwork, something beyond that of object of adoration or sidekick. It’s easy to overlook the canine component of Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Studio), from 2014, also now on view at the Met, but it’s worthy of notice. In the piece, the Chicago-based Marshall, one of our most acclaimed contemporary artists, recalls a turning point from his youth: witnessing for the first time a black artist — his mentor, Charles White — plying his craft, a bustling painting session in full swing. (White is himself the subject of a landmark retrospective that recently closed at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and is now on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through June 9.)

Another famous White House resident, George H.W. Bush’s English springer spaniel Millie, is depicted here on the South Lawn in a painting by Christine Merrill. At the Museum of the Dog, the work is shown alongside a letter from Barbara Bush about the importance of dogs in humans’ lives.

The picture contains, under a table, a yellow Lab-like dog looking at the action, head cocked: He’s curious, he knows something is afoot, and we’re intended to follow his lead and give it our full attention.

He’s not the protagonist, but he’s working all the same to tell us, “Watch this space.”