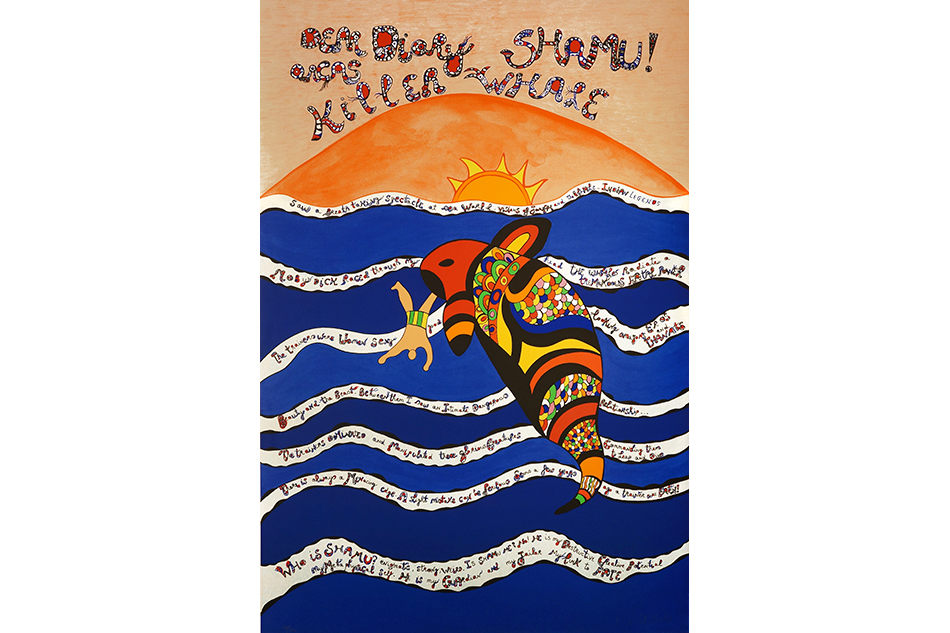

August 31, 2015Niki de Saint Phalle aimed to confront viewers in SHOOT, 1973. Two decades later, she mellowed out and moved to California, producing the 1994 series “Californian Diary,” now on display at Nohra Haime Gallery in New York. © 2015 Niki Charitable Art Foundation, photo © Nohra Haime Gallery. Top: A detail of Californian Diary (Shamu! Killer Whale) playfully relays the late artist’s feelings about whale captivity. © 2015 Niki Charitable Art Foundation, all rights reserved. Photo © Laura Maloney

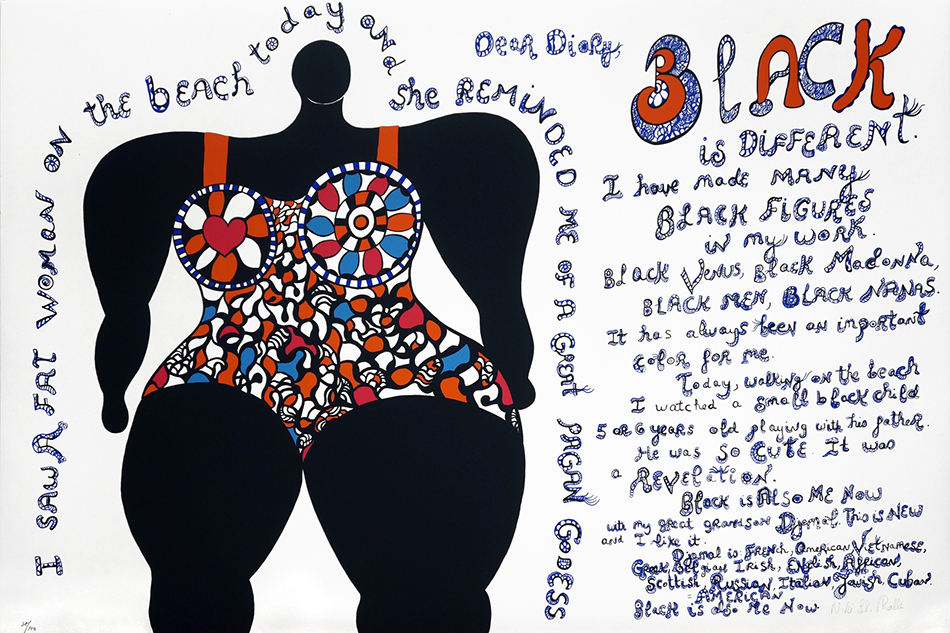

One of the more daring and ambitious female artists of the 20th-century, Niki de Saint Phalle is best known for her exuberant, oversize, colorful sculptures — particularly those of rotund, voluptuous women, or “Nanas” as she called them. But the French-American artist was just as expressive with printmaking, an ideal medium for her to effortlessly articulate the deluge of thoughts that flooded her busy mind over the decades.

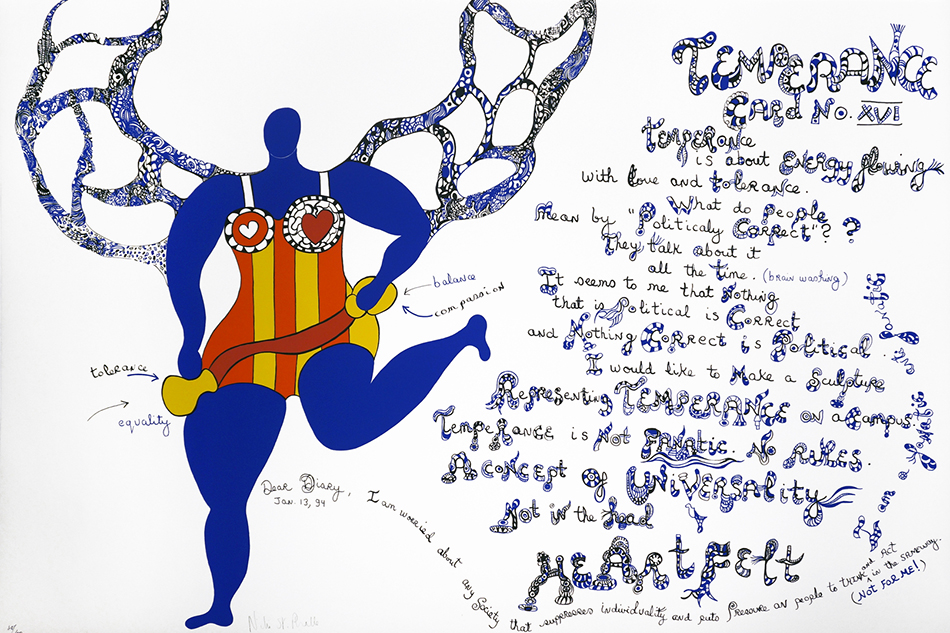

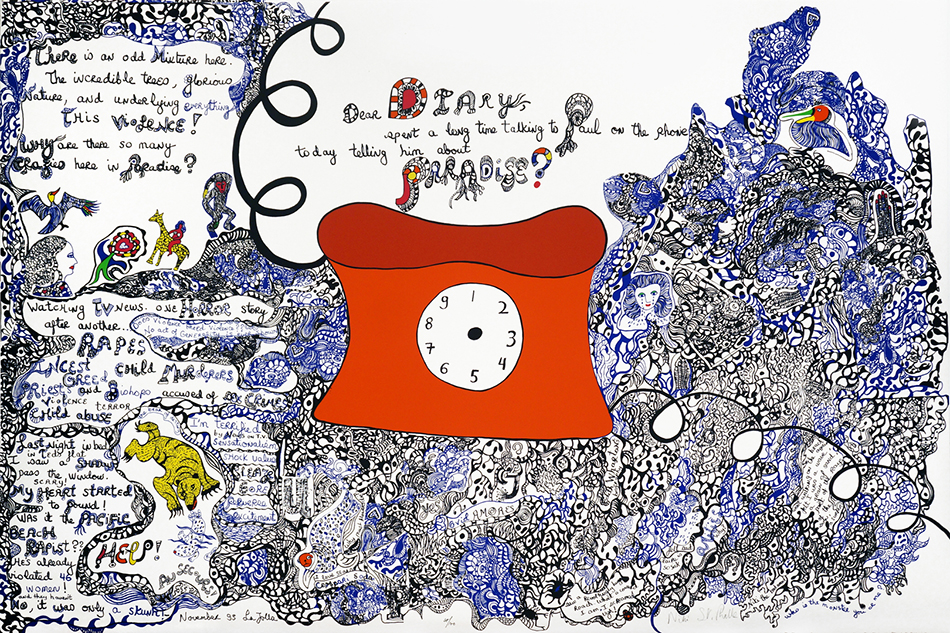

A small show at Manhattan’s Nohra Haime Gallery, on view through September 12, spotlights eight silkscreen prints she produced when she first moved to Southern California, in 1994. Titled “Californian Diary,” the works, from an edition of 100, show a spunky, vibrant artist under the influence of the Pacific sun, playfully weaving together text and image, poetry and politics, like few other artists could.

Saint Phalle, who collaborated with and eventually married the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely, was deeply influenced by the neobaroque wildness of Antoni Gaudi’s Park Güell in Barcelona and Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers in Los Angeles. Her imagery, even in two dimensions, conveys a similar aesthetic, with its bold colors and elaborately patterned forms. In the psychedelic Californian Diary (Shamu! Killer Whale), for instance, Sea World’s celebrated orca isn’t the black and white creature one expects. Rather, he emerges out of the wavy, text-filled water with brightly colored confetti-like shapes as his markings.

Wonderfully irreverent from an early age — she was kicked out of New York’s prestigious Brearley School for applying red paint to statuary fig leaves — Saint Phalle has never been shy about speaking her mind. A former model and stylish beauty with feminist ambitions, she cracked into a male-dominated art world in the early 1960s with her own rebellious, poetic take on art, first drawing serious attention from the avant-garde with her “Shooting Pictures.” These consisted of sacks of paint positioned against a board, which the artist then shot with a rifle to liberate the colorful liquid and annihilate her own demons from her not-so-sunny past. (Saint Phalle revealed later in life, after having a nervous breakdown at the age of 23 and being diagnosed with schizophrenia, that she had been sexually abused by her father.) By the mid-1960s, she was exhibiting with the legendary Alexandre Iolas Gallery in Paris, and she went on to list the illustrious Italian Agnelli family among her main patrons in the late ’70s and ’80s.

A trio of Saint Phalle’s famous “Nana” sculptures, celebrating voluptuous femininity, appears in the show. Photo © Nohra Haime Gallery

But after years of fabricating her giant polyester resin sculptures, Saint Phalle developed lung issues and moved to La Jolla, near San Diego, lured by the curative effects of the dry air and hot sun. She started the “Californian Diary” series during her first year by the Pacific, where she’d go on to create a majestic sculpture garden in nearby Escondido and a giant psychedelic installation on the campus of the University of California, San Diego. The prints are illustrated recollections and stream-of-consciousness editorials about cultural phenomena of the time, ranging from the civil rights movement to the animal-liberation concerns expressed in the Shamu picture.

These works are opinionated and heartfelt with a lighthearted aesthetic touch, and they’re significant not least because several show her lyrical “Nana” figure, a symbol of the artist’s ongoing interest in gender equality and the representation of women. (The French word nana loosely translates to “chick” or “broad.”) “She had always been aware of what was going on in politics, and she was very verbal about it,” says Leslie Garrett, director of Nohra Haime. “Historically, her prints have been autobiographical, and during her time in California she really delved into the ‘Nana’ imagery. But we also see a lot of California inspiration — a brighter palette, for instance. You can see she was happier when she was there.”

By the early 2000s, Saint Phalle’s breathing problems caught up with her, and she died of emphysema in La Jolla in 2002. She may have been driven by social activism, but she clearly embraced the fantastical, and in the context of California, Saint Phalle captured some truly magical sunshine.