November 1, 2020A house is the expression of the person who lives there,” says Jim Olson, the Seattle architect whose work has proved that many times. Olson is calling from his own house, which he’s named Longbranch and which he began building as an 18-year-old with $500 from his father and the help of a local carpenter.

Originally a 200-square-foot cabin, it has grown through multiple renovations over more than half a century into a 2,200-square-foot getaway. “I’m looking out a tall window at trees framing the beach,” he reports, adding, “I’d rather be here than anyplace else in the world.”

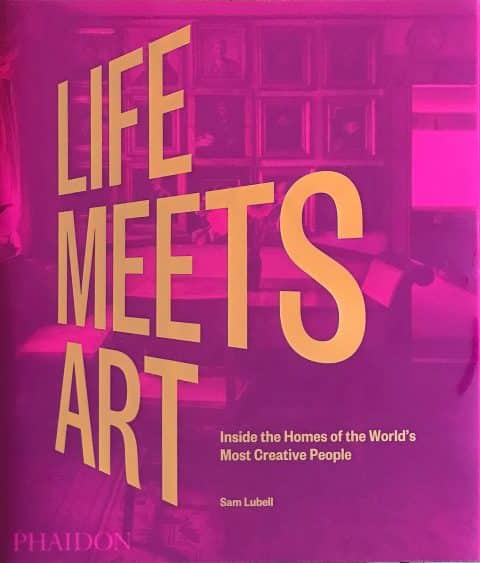

“A house is the expression of the person who lives there” is also the theme of architecture journalist Sam Lubell’s new book, Life Meets Art (Phaidon), which features 250 homes of people who, like Olson, are known for their creativity.

The homes are arranged alphabetically, starting with Alvar Aalto, whose Helsinki living room is filled with his now-iconic furniture, and ending with Anders Zorn, the great Swedish painter, whose fantastical lodge in Mora is one of the most unusual houses in the book. (Many of the homes, including both Aalto’s and Zorn’s, are open to visitors. A few can even be rented overnight.)

It’s natural to want to see how other people — especially artistic people — live. If Olson were on Zoom, you might be looking over his shoulder at some of the objects in his house. But unless Zoom introduces a time travel feature, you won’t be seeing the great painter Peter Paul Rubens on your screen, or the designer Russell Wright or the Gilded Age novelist Edith Wharton (who also wrote a guide to decorating) or Les Misérables author Victor Hugo. But their homes are all in the book.

The hope, of course, is that you’ll see things in the residences that help you understand their famous owners.

It works best when the owner is also the creator — after all, how much can you learn about Frank Sinatra from a photo of his sleek house in Palm Springs knowing that, according to the book, his architect, E. Stewart Williams, had to convince him not to build a Georgian-style mansion.

By contrast, much of the furniture in Hugo’s Paris home, Lubell tells us, was “created by Hugo himself, working with carpenters to combine disparate pieces into complex new” ones.

The connections between owner and home aren’t always apparent. There is nothing mysterious about Agatha Christie’s living room in Devon. Nor is Charlie Chaplin’s manor house in Switzerland particularly cinematic.

There are no signs of satire in Mark Twain’s Hartford manse. And, to be honest, I don’t find Pablo Neruda’s home in Chile to be particularly poetic. Still, the photos are beautiful and the commentary interesting; Lubell, who has done seven other books for Phaidon, is a master of the form.

And there are many payoffs. Salvador Dalí’s house on Spain’s Costa Brava and Jean Cocteau’s getaway in the South of France are both Surrealist extravaganzas. Cocteau graffitied the walls of the Villa Santo Sospir during World War II “to vanquish the spirit of destruction that has dominated our era,” he explained. “We have decorated surfaces that men dream of destroying.”

The Greenwich Village apartment of TV satirist Amy Sedaris has so much personality, Lubell writes, it should have a program of its own. Sedaris’s place bears a familial resemblance to the uptown apartment of Iris Apfel, a New York grande dame and fashion pioneer who decorates as fearlessly as she dresses.

Some of the sites in the book are familiar: Luis Barragán’s pink-walled home and Frida Kahlo’s blue-walled house, both in Mexico City; Francis Bacon’s famously messy studio in Dublin; the Eames House in Pacific Palisades; and Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan.

If they’re overexposed, it’s because they’re so successful — not just as architecture but as reflections of their owners’ sensibilities.

And there are plenty of lesser-known houses in the book. One is a cave-like dwelling outside Mexico City, a kind of concrete organism owned and created by Surrealist designer Javier Senosiain, punctured by plastic skylights and porthole windows. Senosiain might appreciate the French Riviera residence of Pierre Cardin, designed by Hungarian architect Antti Lovag, who once called straight lines “an aggression against nature.”

The Tuscan home of artist Niki de Saint Phalle is another eccentrically free-form creation, with, Lubell writes, “a hallucinatory quality, as though a fairy tale had been blown to bits and reassembled.”

Many of the houses are by male architects acting as their own clients. Norman Foster carved a glass-and-steel house into a hillside in the South of France. In Los Angeles, Frank Gehry resides with beams that meet at acute angles, and Steven Ehrlich, a master of indoor/outdoor living, has seemingly made a tree much bigger than his living room part of his living room.

There’s nothing new about architects doing their best work for themselves. The Brussels home of Victor Horta is a turn-of-the-century Art Nouveau triumph. Gerrit Rietveld, too, inhabited his most fully realized work, the Schröder house. (Who knew that he lived there with Mrs. Schröder after Mr. Schröder died?) Charles Moore was a postmodernist, and his Austin home — filled with gaudy architectural fragments — demonstrates just how wedded he was to that approach. It has all the color that Henry Moore’s studio, on the facing page, lacks.

from Gufram and a white Ottawa sideboard from BoConcept. Photo by Ortal Mizrahi, courtesy of Karim Rashid Inc.

Furniture designers also like to look at their own creations: Karim Rashid, Dieter Rams, Jean Prouvé, Gustav Stickley, Verner Panton, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, George Nakashima, Wharton Esherick and many others are represented by houses filled with items they designed.

Fashion designers, on the other hand, apparently like to look at themselves — Diane von Furstenberg’s living room is dominated by a large painting of Diane von Furstenberg, and Zandra Rhodes’s penthouse displays a bust of Zandra Rhodes topped by her all-important pink hair.

Beyond these insights, there are some wonderful lessons to be drawn. Olson’s house is more authentically Olson than any of his better-known works. It’s where he tries out ideas and studies dimensions. The window he’s looking through is about five and a half feet wide and nine and a half feet tall — proportions, he says, that make him feel comfortable.

“It’s an intuitive thing — if you made that window square, it wouldn’t work,” says Olson, noting that the edges of the glass are hidden, “so you feel like there’s nothing between you and nature.”

When he brings potential clients to the house, he says, “they like it, and they want me to do some of the same things, but their lifestyles are grander.” To do it modestly, he had to do it for himself.

It’s fortuitous that, thanks to the book’s alphabetical organization, Olson’s Longbranch faces Wild Bird, the Big Sur home of Nathaniel Owings. Wild Bird says far more about Owings, a cofounder of the mega-firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, than that office’s skyscrapers ever could.

An A-frame of reclaimed redwood with a rough stone floor and concrete beams with embossed patterns, it is at once naturalistic and cozy. Those qualities aren’t normally associated with SOM, and you wouldn’t know they were priorities for Owings without this valuable book.