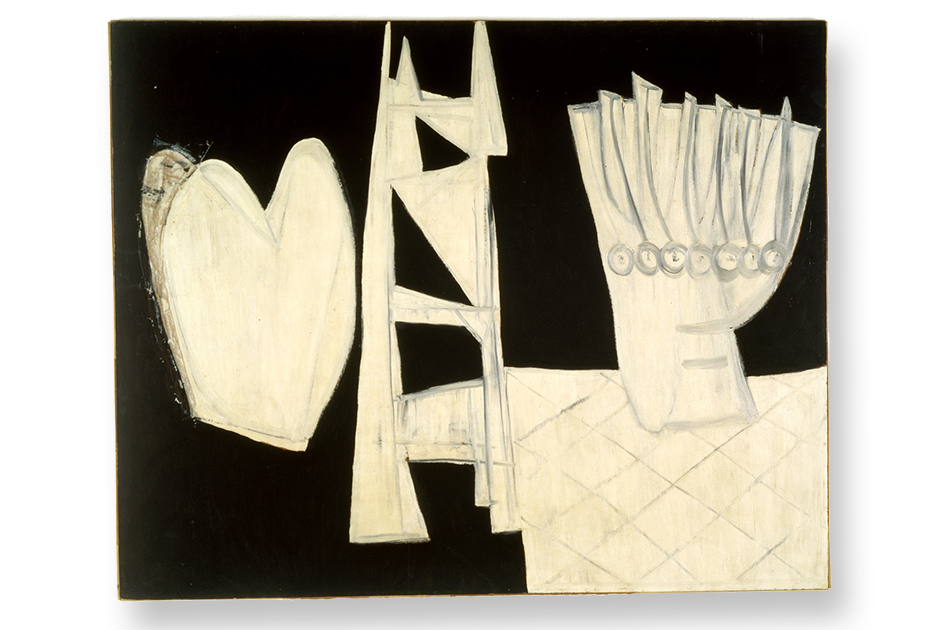

August 1, 2014The Poet, 1947. Photo courtesy of the collections of Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko. All Motherwell images ©VAGA, NY

Robert Motherwell: The East Hampton Years, 1944-52,” an exhibition on view at Guild Hall, in East Hampton, New York, until October 13, celebrates the precocious early paintings of a pioneering Abstract Expressionist (1915–1991). Owned by major museums across the United States, these works have been largely overshadowed by Motherwell’s bold black-and-white “Elegy to the Spanish Republic” paintings, mostly from the 1950s and ’60s, but, in 1985, the artist said of his time on the East End, “I did some of the best work of my life there.” And, now, thanks to this exhibition, everyone can see the remarkable way he melded representational images into an abstract framework.

For this preview, Introspective has asked Phyllis Tuchman, the respected, longtime art historian and journalist, to interview Phyllis Tuchman, the budding exhibition curator and the force behind the Guild Hall Show, about these extraordinary works.

As a writer turned curator, what did you enjoy the most about organizing the exhibition?

I was able to bring together for the first time a body of work by the pioneering Abstract Expressionist that is barely known. Back in those early years, he was hailed by influential figures like MoMA curator Dorothy Miller, critic Clement Greenberg and collector Nelson Rockefeller. But today Motherwell is mostly known for paintings he executed during the 1960s and ’70s. No one would have assigned me to write an article about these compelling oils without a juicy peg.

What is the main lesson visitors to Guild Hall will take away from the exhibition?

In more than two dozen works, gallery-goers will see how Motherwell, who was born and raised on the West Coast and studied at Stanford, Harvard and Columbia, created bold abstractions right from the get-go, with large-scaled, geometric shapes and few colors. Illustrations do not vividly record the caked surfaces, nuanced palette and varying dimensions of the works.

Line Figure in Beige and Mauve, 1946, is one of 25 paintings included in the show from Motherwell’s early years. Photo courtesy of Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art

Motherwell seems to have never rested in the first five decades of his career. What did you do to show how prolific he was?

Motherwell painted; made collages; edited the “Documents of Modern Art” book series, the journal Possibilities and the canonical anthology “Dada Painters and Poets”; held solo shows at both Art of This Century and the Kootz Gallery; and was featured in prestigious surveys of contemporary art. For the exhibition I borrowed a range of paintings whose style evolved over a period of time and in a display case show the astonishing number of publications with his byline. As a journalist, I could have written about his awesome prolificacy but sometimes you’ve got to see it — not read it — to believe it.

Tell us a bit about Motherwell’s house, where he painted many of these works and which features prominently in the exhibition. What made it so interesting?

When an artist says he made some of his best work in a certain space, you want to know more! It was a two-story building on Georgica Lane, made from a pair of salvaged Quonset huts and a greenhouse roof. It served as a sort of hub for the AbExers living and working in the area at the time — Willem de Kooning even made parts of his cherished “Woman” series there in 1953, when Motherwell was out of town. Unfortunately, the house was razed in 1985 to make way for a larger, more conventional home, but I was able to track down photographs. The show features 13 mounted prints of those images, and we have borrowed an extraordinary scale model of the house made years ago by Harry Fishman, who lives in Sag Harbor.

How did Motherwell combine a cubist aesthetic with Surrealist techniques?

The artist reworked — and often renamed — his pictures. Some of his titles compel viewers to notice representational imagery while others make you notice geometric shapes. Take the St. Louis Art Museum’s In Beige with Sand, 1945, originally exhibited as Abstraction with Scallops. Will viewers notice bivalve mollusks or circles? Did Motherwell succeed in making you see the painting both ways? It wasn’t an either/or proposition for this former philosophy major.

In those early years, Motherwell was hailed by MoMA curator Dorothy Miller, critic Clement Greenberg and collector Nelson Rockefeller. But today he is mostly known for paintings he executed during the 1960s and ’70s.

How are writing and curating similar — and different?

Journalists need to convince editors to commission articles. Curators need to convince museum directors, advisory boards and trustees to entrust them with a costly show. And getting key loans is a story in itself.

What’s the biggest lesson you’ve learned from this experience?

As a writer, I can suggest Motherwell’s earliest paintings merit more attention. As a curator, I can let people see the remarkable truth of this for themselves.