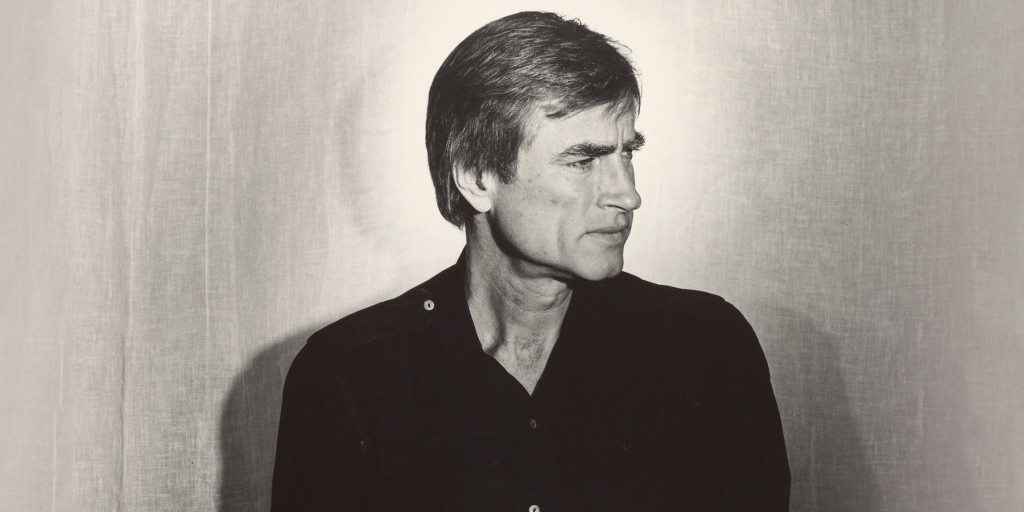

March 28, 2016A new show at Los Angeles’s Getty Museum spotlights the photography collection of Sam Wagstaff (portrait © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation). The late curator’s exquisite holdings — including Timothy H. O’Sullivan’s Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle, New Mexico, In a Niche Fifty Feet Above Present Cañon Bed, 1873 — create a chronicle of the medium, from its earliest days in the 1800s through the middle of the 20th century. All photos courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, unless otherwise noted

Sam Wagstaff’s name carries with it an air of lurid glamour. The role he famously played in Robert Mapplethorpe’s life and career — as lover, mentor and patron — turned out to be only his last and most conspicuous distinction. Long before they met, Wagstaff (1921–87) had established himself as a visionary curator of painting and sculpture. He organized, for example, the first museum show of minimalism at Hartford, Connecticut’s Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, in 1964, and also gave the sculptor Tony Smith his first museum exhibition two years later. Throughout the 1960s, he provided consistent curatorial — and sometimes financial — support to a roster of mostly young, often unknown, artists who today constitute a pantheon of the era: Andy Warhol, Ray Johnson, Agnes Martin, Richard Tuttle, Michael Heizer, Mark di Suvero and Walter De Maria, among them.

His name comes up again with “The Thrill of the Chase,” an exhibition of photographs from the Wagstaff Collection at the J. Paul Getty Museum, in Los Angeles, on view through July 31 and coinciding with simultaneous Mapplethorpe retrospectives at the Getty and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The Wagstaff Collection is the backbone of the Getty’s photography holdings, arguably among the top three museum collections of photographic works in the world.

In 1972, Wagstaff — pedigreed, wealthy, unconventional and still strikingly handsome at 50 — met Mapplethorpe, a young artist half his age. Mapplethorpe was making collages and assemblages and had yet to claim photography as his medium. At the time, it was not taken seriously in the art world. Wagstaff, a champion of the avant-garde, was often vocal in his repudiation of photography as nothing more than an applied art. It’s an opinion that stands in stark contrast to the instrumental part he would play throughout the 1970s in elevating the medium’s stature into the realm of fine art and in establishing the art market for photographs.

American photographer Arnold Genthe shot this portrait of playwright and poet Edna St. Vincent Millay around 1917.

Mapplethorpe was responsible for turning Wagstaff’s attention to photography. When the two attended a 1973 exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art called “The Painterly Photograph,” Wagstaff stood in front of The Flatiron, 1904, by Edward Steichen, and had an epiphany. It was the first photograph in which he recognized and acknowledged the “subject” and the “image” to be inextricably linked and of equal weight. For him, it was a visual construction in which shape, tone, light, space and juxtaposition all danced on the surface of a single piece of paper — nothing less than a perfect alchemy of emotion, perception and (significant) form.

“In the face of such a picture,” Wagstaff later told a group of art students, “I kept looking back on that period in American painting and sculpture and trying to find something that was of equal stature. And I don’t think there is, probably for five years on either side of that picture.” He added, “It seemed to me like a stupendous milestone in the advancement of the human mind in America.”

The Flatiron prompted Wagstaff’s immediate interest in collecting photographs, but at Mapplethorpe’s suggestion, he waited until Patti Smith did a tarot-card reading to determine whether it was an auspicious venture. The reading was very favorable. Wagstaff, with a twinkle in his eye, liked to tell reporters that he began to collect photographs “with Patti Smith’s approval.”

At an auction in London in 1974, Wagstaff made a purchase of such stunning audacity it incited an international controversy. On the block at Sotheby’s was an album of 94 portraits by Julia Margaret Cameron. The artist had assembled it as a gift to her friend Sir John Herschel. The gavel came down on Wagstaff’s bid for the “Herschel album,” as it was called, at an unprecedented $130,000, an astounding sum for photography then.

Mrs. Herbert Duckworth, captured in 1867 by British photographer Julia Margaret Cameron

After the Sotheby’s sale, albums that for generations had been considered useless heirlooms, stored away in attics in Britain and France, were dusted off and brought in to the auction houses for appraisal. Wagstaff’s purchase unearthed an abundance of new material — troves of valuable albums and prints that would eventually allow the history of photography to be revised and amended.

Wagstaff’s sudden turn to photography shocked his art-world colleagues. This amused him and also spurred him to become among the medium’s most vocal advocates, on a par with the venerable curator John Szarkowski, of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Wagstaff was fond of offering this canny declaration: “Gustave Le Gray made pictures in the 1850s. He’s the greatest photographer of all, the best that there has been, and the textbooks hardly mention him. It’s like leaving Rembrandt out of a history of Western art.” (No surprise, then, that this past February, Christie’s sold Le Gray’s Bateaux quittant le port du Havre, 1856–57, for $965,000.)

Within a decade, Wagstaff had amassed a collection of 26,000 photographs. And while he was a serious collector regarded for his scholarly connoisseurship and original eye, he was also a serial collector. As abruptly as he had turned to photographs, in 1984 he sold his entire cache to the Getty as one of the five founding collections for the museum’s photography holdings. It paid $5 million for his stash, a fortune at the time.

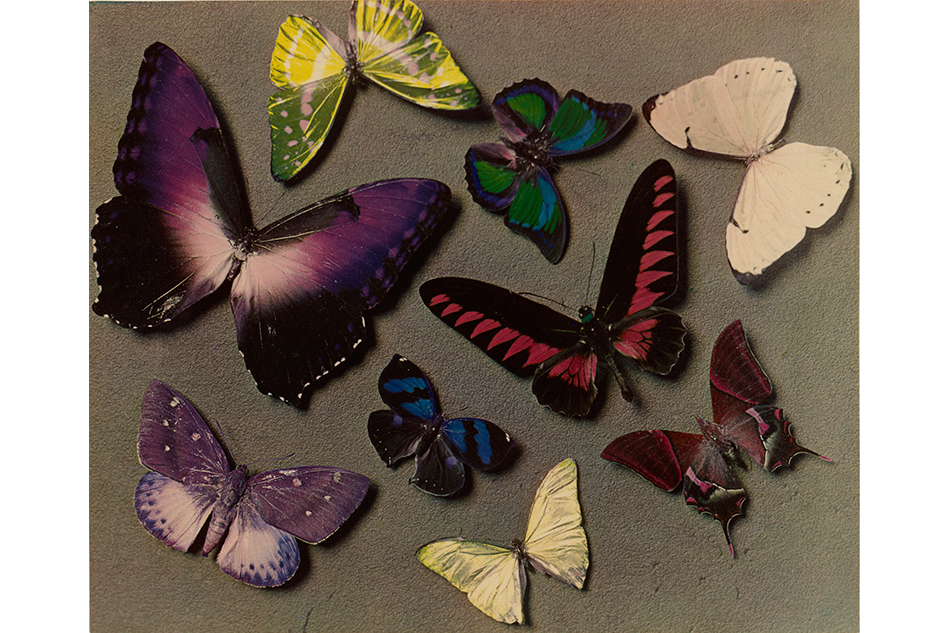

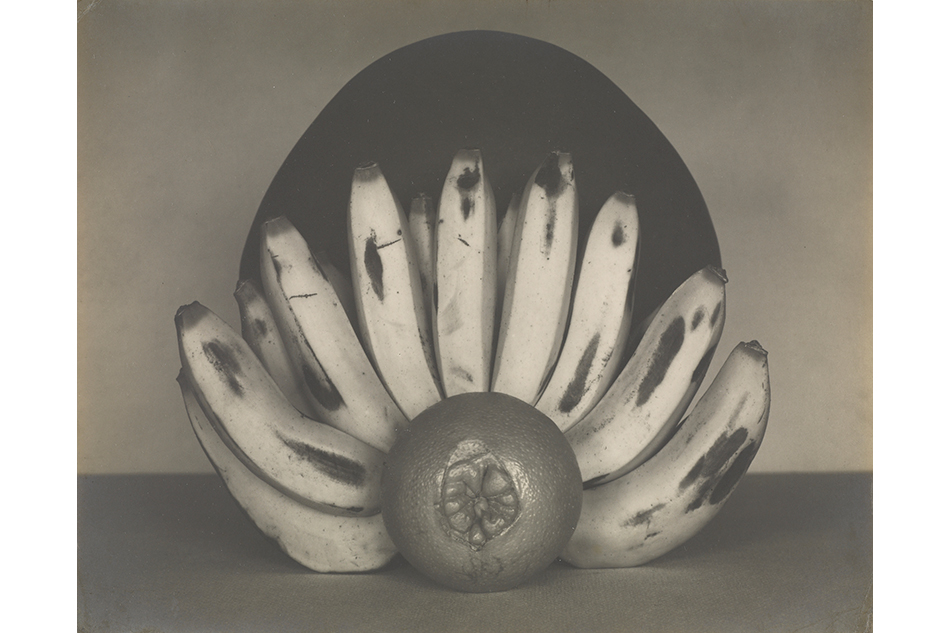

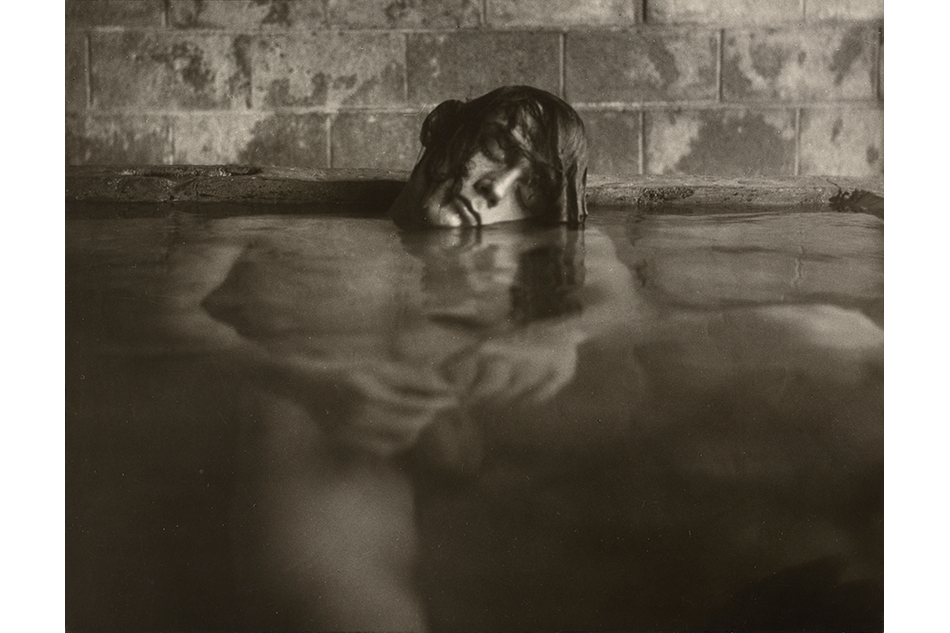

Among the treasures in “The Thrill of the Chase” are works by Julia Margaret Cameron, Peter Henry Emerson, Nadar, Timothy O’Sullivan, William Henry Fox Talbot and Carleton Watkins. Collectively, they represent the finest examples of the printing techniques on which the medium, and its history, were built — from calotypes, tintypes and daguerreotypes to collodion and albumen processes.

Wagstaff (left) poses with Robert Mapplethorpe, in a 1974 portrait by Francesco Scavullo. Courtesy of the Francesco Scavullo Foundation

As a cultural history, the narrative of Wagstaff’s life parallels a number of concurrent strains in the course of the past half century: One is the evolution of the gay rights movement; another is the elevation of photography to equal stature among the fine arts, becoming, finally, according to New York Times art critic Holland Cotter, “the common language of modern history.”

In the photography sphere, Wagstaff assumed the leading role for a small and select group of early collectors who were gay. Indeed, the sexuality of the collectors and curators who put such a focus on photography — not only Wagstaff but John Waddell, Paul Walter, Pierre Apraxine, Howard Gilman, not to mention the dealer George Rinhart, along with the very closeted, indeed married, Harry Lunn — should not remain a mere footnote in art history.

By the time they were finished, their respective photography collections exemplified an entire visual record of the 19th and 20th centuries at their finest, resulting in a seminal trove of photographic excellence. Each of them had started at zero yet went on to create collections that warranted acquisition by the likes of the Met, MoMA and the Getty.

Not only was it worth the time and effort in terms of their handsomely rewarded investments. It was with pleasure as well that these photography collectors — with Wagstaff as a guiding force — left what was once considered a marginal form safely in the hands of the nation’s most august art institutions. Out of such foresight, connoisseurship and labor, we benefit. “The Thrill of the Chase,” a careful selection from the Wagstaff treasures, is the crème de la crème of an already sublime confection.

Browse Fine-Art Photography on 1stdibs