September 5, 2012Daniel Mendelsohn, the author, in his New York City apartment. He bought the 1940s armchair (one of a pair) at the 25th Street flea market. Top: A pair of Robsjohn-Gibbings ebonized armchairs sit beneath a 1920s Venetian chandelier, both found through 1stdibs. All photos by Josh Gaddy

The Greeks had a phrase for it: the arkhê kakôn, “the beginning of the troubles.” The arkhê kakôn in the Trojan War, for instance, was when a queen named Helen decided to run off with an attractive houseguest; she happened to be married, which was . . . the beginning of all the troubles. My troubles began 10 years ago, at my sister’s wedding in Baltimore, when I kept sneaking out of the reception to check the online auction results for a T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings sabre-leg occasional table. I knew then that I had a Neoclassicism problem.

Actually, it had begun much earlier, when I was around 11 or so. I was an introverted, studious kid, already hooked on Greek mythology; every Sunday I’d accompany my dad to the local public library and scour the ancient history section — a row of gunmetal gray stacks toward the back of the room — for new books about Greece. One day I spied a slender black spine: Furniture of Classical Greece, by someone with the tongue-twisting name of T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings. Although I had no clue who that was, in the early 1970s I wasn’t completely ignorant about furniture, either: my mother, who’d taken some art classes when she was at Hunter College in New York City in the late 1940s and early 1950s, had a great eye, and the living room of our split-ranch house in a Long Island suburb was (as I only now realize, 40 years later) a kind of mini-seminar on mid-century design. The neighbors didn’t know what to make of the Saarinen womb chair that Mom had bought while she was still in high school, but she took the time to explain to us why it was “good.”

The marble-topped 1940s Italian console in Mendelsohn’s foyer was purchased through 1stdibs; the Venetian mirror was a $75 find at New York’s 17th Street flea market.

Still, I’d never really thought about what Greek furniture might look like; when I thought about the ancient Greeks I thought about racy myths, truncated statues of naked people and beautiful marble temples. (I spent so many years during junior high and high school trying to build a 1:100 scale model of the Parthenon that my parents dubbed the workbench in our basement “Athena’s Table,” a name it still goes by.) Curious, I pried the slim volume from its neighbors. There, on the cover, was a picture of the most beautiful chair I’d ever seen: a klismos. What was interesting to me was how like the furniture in my parents’ living room it was: clean in its lines, spare in its ornament, subtle but powerful in its overall effect. I was fascinated, as I leafed through the large format book, to see ancient reliefs in which this very chair was depicted. It seemed amazing that the ancient Greeks had, well, modern furniture.

I was hooked. I checked out the book, and for the next week I ogled the photos of the sparely elegant ancient furniture that Gibbings had reproduced in his designs for Saridis — and that had so greatly influenced his contemporary designs for Widdicomb. I didn’t know any of this then, of course. At the time, I simply told myself that one day I would own a klismos.

So that was the real beginning, and there I was, four decades later, surreptitiously bidding on that exquisite little occasional table. It would be the first piece of Gibbings that I owned. I’m still embarrassed to think that my beaming smile at the wedding was largely because of a successful bid on a heavily scuffed side table made in 1954.

A lot of collecting — well, a lot of studying auction catalogs and shelter magazines, and many trips to the flea market — had intervened between the public library in 1971 and that summer day in 2002. After high school I went on to major in Classics at the University of Virginia — whose campus was, in fact, designed by Thomas Jefferson to be a living seminar in architectural Classicism: each of the original classroom buildings was done in a different combination of classical styles, so that students walking by would learn to appreciate the orders. Then, after doing graduate work in Classics, too, I quit academia and embarked on my writing career. It was only after I moved to New York City, in 1994, to become a writer that my hunt for Neoclassical style furnishings began in earnest.

“I REMEMBER IN PARTICULAR A SQUARE, SABRE-LEGGED GIBBINGS LAMP TABLE THAT HAD BEEN SPRAY-PAINTED BLACK AND DECORATED WITH METALLIC SILVER CURLICUES — NO DOUBT, I ALWAYS IMAGINED, BY THE BORED TEENAGED DAUGHTER OF THE ORIGINAL OWNER, SOMETIME IN THE EARLY 1980S. I GOT IT FOR $80.”

When Mendelsohn received this Robjsohn-Gibbins lamp table, it was painted black with silver curlicues.

If you lived in New York City in the mid-1990s, the flea market on three empty lots at the intersection of Sixth Avenue and 25th Street could be a rich source of serious furniture. I used to meet my younger brother at seven in the morning there, and we’d spend three or four hours scouring the stalls. He was avidly amassing Shelley teacups; I, naturally, went after anything even remotely classical. (There I acquired, for $50, a pair of early Gibbings side chairs for Widdicomb, featuring sexy, deeply curved backs: an early triumph. The bubble-gum-pink Naugahyde seats have long since been recovered.) I particularly loved what serendipity could achieve. In 1994, when I’d just become interested in Venetian glass, I stumbled across an interesting bulbous lamp so dirty I thought it was old brass until I took it home and washed it, at which point I saw it was made of glass — glass in a combination of aventurine, white, ebony and clear that marked it as a product of the great Dino Martens. One Sunday afternoon three years later while (as my friends and I call it) “fleaing,” I stumbled across a mate. The total I paid for the two was $360.

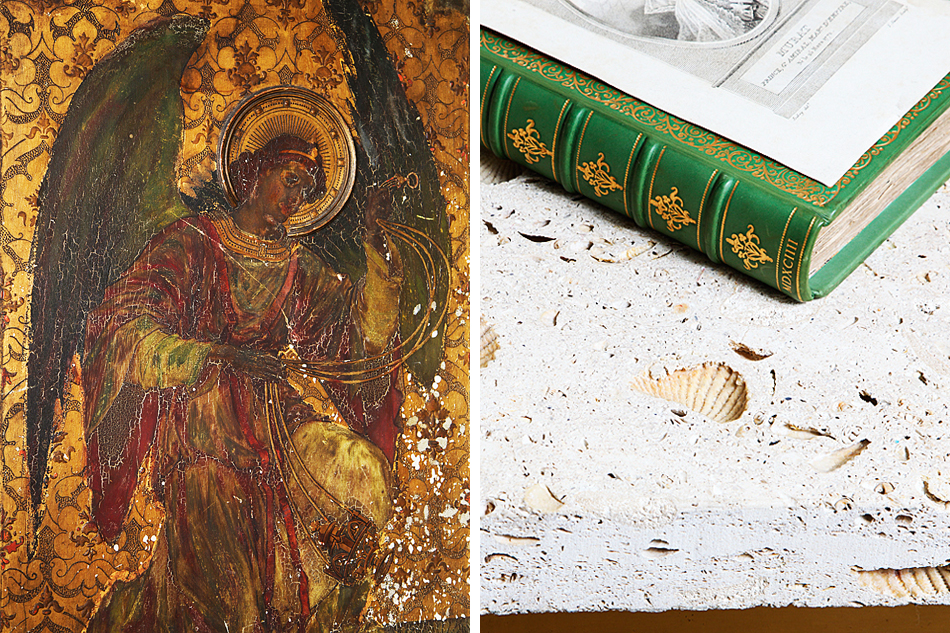

And a good thing, too: In those days I had just started freelancing and didn’t have two nickels to rub together. I still remember the anguishing morning I came across a cast of part of the bas-relief frieze that ran around the inner wall of the Parthenon, and had to pass it up because the $100 asking price was more than I could afford. But the Angel of Collecting was watching over me: a dozen years later I came across an identical cast, taken from a 19th-century school building that was being demolished in upstate New York, and I snatched it up.

The number of flea markets began diminishing as online shopping exploded. After that first delicious purchase through eBay, I started snapping up Gibbings pieces that were in bad shape for low prices and having them restored. I remember in particular a square, sabre-legged Gibbings lamp table that had been spray-painted black and decorated with metallic silver curlicues — no doubt, I always imagined, by the bored teenaged daughter of the original owner, sometime in the early 1980s. I got it for $80, and the restoration cost me another couple of hundred; it and an identical mate, which I got through an online auction a few years later, now flank my bed. Years later I bought the amber glass lamps that sit atop them, with their vaguely neoclassical marble-and-brass bases.

“The classical objects make for a lot of purity,” says Mendelsohn, “so I think it’s important to have a few out-there, fun pieces, like this floral gilt floor lamp.”

That was after I moved into my current apartment, in a historic Art Deco building in Chelsea — one I decorated with the choicest of my old finds (many newly upholstered for the occasion) along with a significant number of new acquisitions, which I can truthfully say nearly all came from 1stdibs. I have to admit it: I’d still rather nose around online — preferably without the search function, which makes things a bit too easy — than go to a shop. Scrolling through 1stdibs’ new listings on a Wednesday afternoon is one of the few things that can still give me the thrill of the hunt that I enjoyed so much in those early flea-market days, when I first started chasing after “classica,” as an editor friend of mine teasingly calls the category that always catches my eye: certain objects that are clean of line and spare in detail, that sport a sabre leg, perhaps, or maybe a vaguely antique flourish, a Greek key border or Pompeian motif.

That’s how I got my lovely 1940s Italian horn-shaped sconces in my living room and, just below, the brass-and-fossilized travertine console, with its surprisingly delicate goat’s feet, on which sit a cast-metal Ares and Aphrodite, snapped up at a flea market in 1995; it’s how I landed the sleek ebonized Gibbings armchairs in my living room, and, in a slightly different vein, the Greta Grossman console in the bedroom where my flat-screen sits. (I’m a leg man, what can I say?)

And of course it’s where I got my greatest treasure: a pair of klismoi, to give them their proper plural, the perfection of which I first glimpsed on a book cover four decades ago. They sit on either side of a simple Deco console in my living room, beneath that giant cast taken from the Parthenon. Which seems just right.