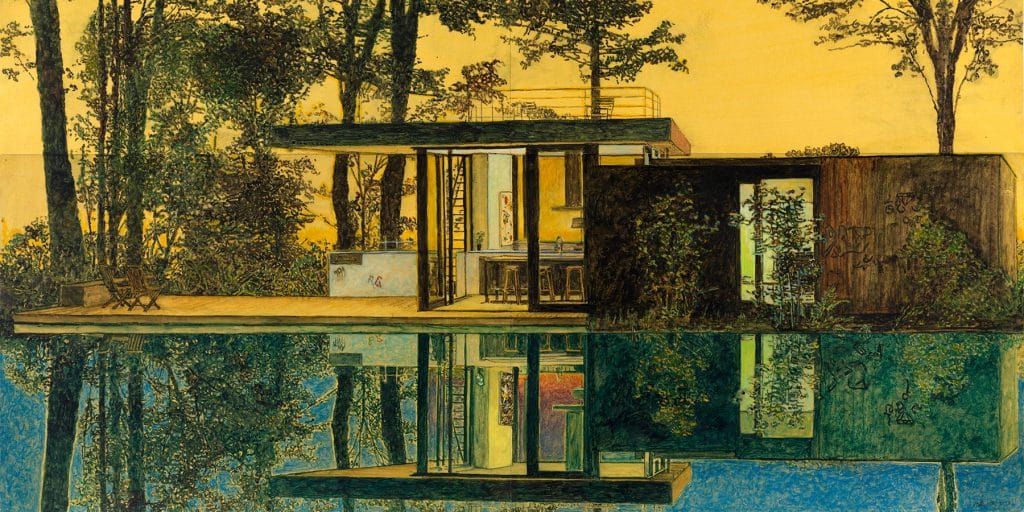

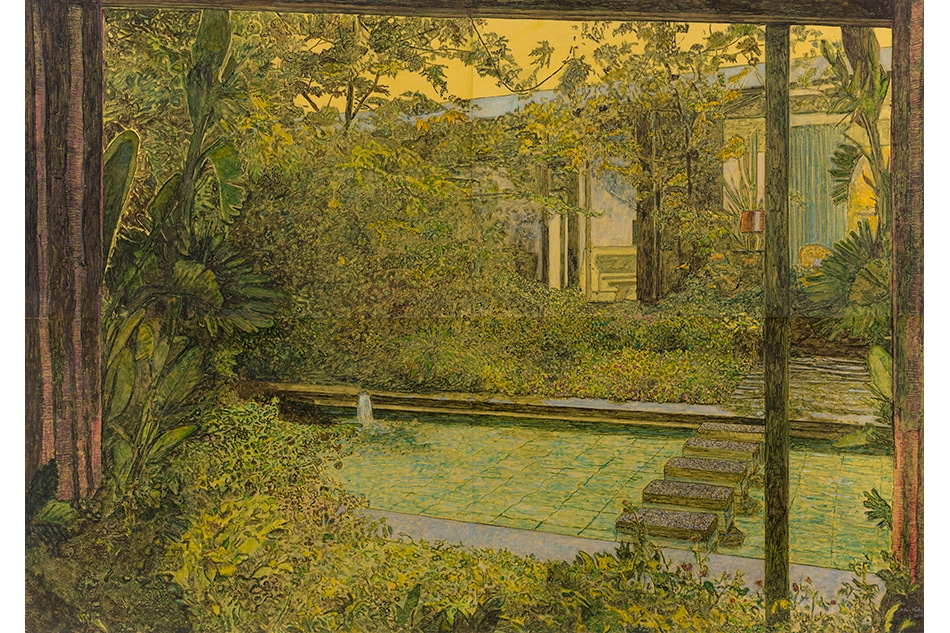

November 20, 2017The subject of the show “Millefleurs,” on view at San Francisco’s Hosfelt Gallery through December 2, Düsseldorf-based artist Stefan Kürten says that the subtlety of the disturbing elements in his work allows people to think each is simply “a beautiful painting” (portrait by David Stroud). Top: A Kürten piece from earlier this year, Illusions, included in the show. All photos courtesy of Hosfelt Gallery

In Stefan Kürten’s paintings, elegant modernist houses — some of them taut International Style pavilions, others more-laid-back California ranch houses, but all of them well tended — nestle in lush, sometimes overgrown landscapes. But things are not necessarily what they seem. In Illusions (2017), the painting inside a house doesn’t match the one in the swimming pool’s reflection of the structure, and while the water in the pool is deep blue, the sky above is an eerie yellow. In Before Dark (2017), a house’s front door is not only obscured by tree branches but blocked by a pair of circular, brick-rimmed openings that seem to contain reflecting pools. What, you wonder, is the artist trying to tell us?

The work of the Düsseldorf-based Kürten, on view in “Stefan Kürten: Millefleurs” at the Hosfelt Gallery, in San Francisco, through December 2, delves into the relationship between reality and desire. (Full disclosure: I contributed an essay to the show’s catalogue.) Or, as the gallery’s founder, Todd Hosfelt, puts it in describing the work in the exhibition — the artist’s eighth at the venue — it “is so much about memory and how inaccurate our memories are.”

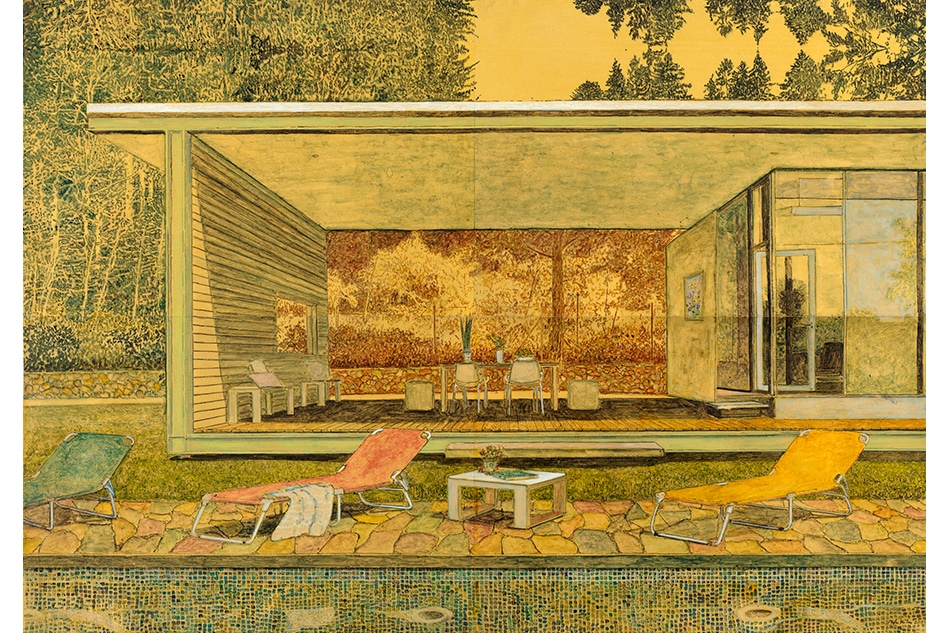

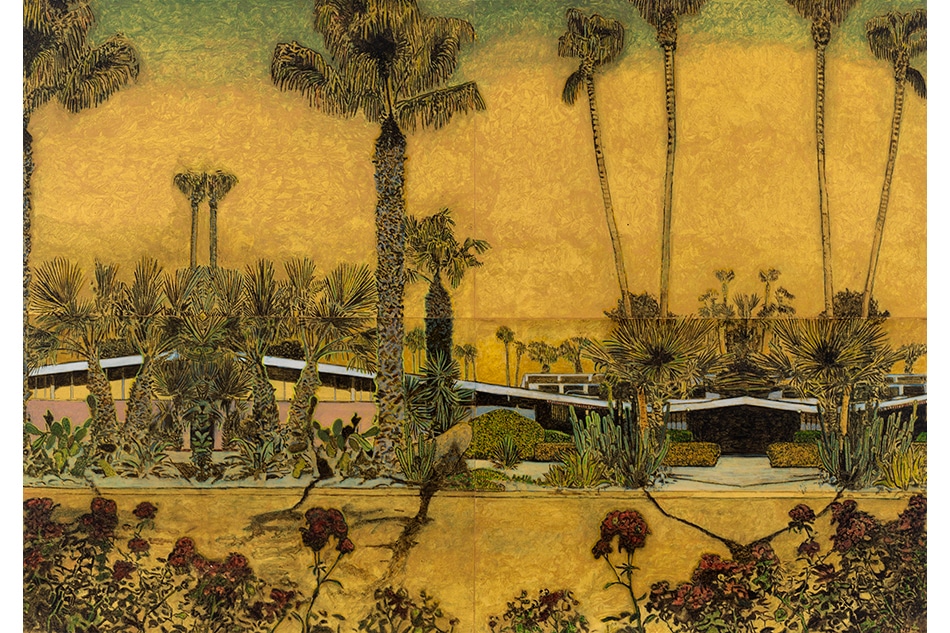

Kürten, who generally uses paper prepared with a metallic gold background on which he applies ink and acrylic with a brush so fine that the paintings look more like drawings, is living proof of this phenomenon. About 10 years ago, he wanted to photograph his old school but was disappointed that it didn’t look anything like what he remembered; he thought it must have been altered. But the school’s director informed Kürten, as he was standing in front of the building, that it was still in its original state.“So, I used photos of a school from a book. The photo reminded me more of my school than the real thing,” the artist says. In his work, Kürten usually starts with a photograph of a building (he has files full) that he photocopies and then proceeds to alter. These structures “look like they could actually exist,” he says, “but I would never paint a real place.”

The fact that Kürten depicts architecture that is essentially fictional has not deterred viewers from insisting that they not only recognize the building in a painting but know its exact location. Those reactions, Kürten explains, “helped me to know what I did want: an architecture that could be anywhere.”

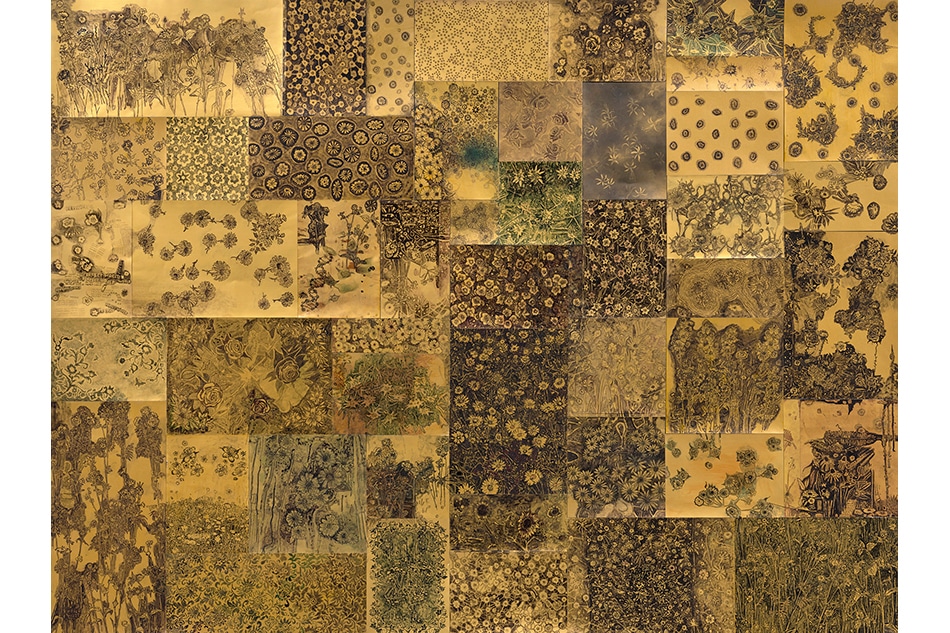

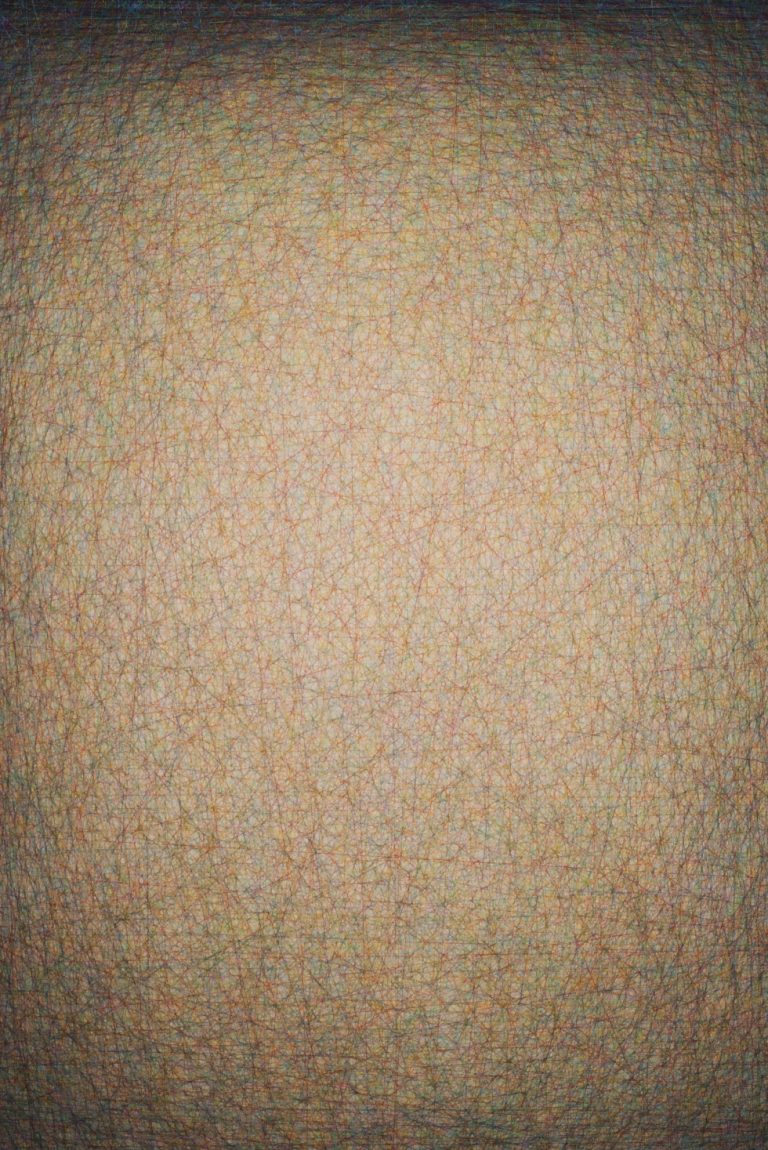

A detail of Perfect World, 2016–17. The largest work in the show, it is also one of the few that doesn’t depict architecture, instead referencing the wallpaper in the kitchen of the artist’s late mother.

It was Kürten’s trips as a boy accompanying his parents on their weekend house-hunting forays that led to his fascination with postwar-modern architecture and what Kurten calls its “dream of a perfect world.” But perfection is elusive in the artist’s imagery; instead, ambiguity is the norm. Moreover, as Hosfelt notes, although Kürten’s paintings “are about being human, there’s never a human in them.”

The artist admits that this makes some people uncomfortable, but he insists that it is a deliberate choice. “People will look right away at the person in the painting — they’re looking for a story,” he explains, adding that instead, he hopes “you can project yourself into my paintings.”

Not all the paintings in the exhibition depict houses. The largest one, Perfect World (2016–17), a 9-by-12-foot work on canvas, updates a picture Kürten did in the 1980s in response to his late mother’s entreaty to “paint something beautiful for once.” The first version, a delicately colored allover floral pattern based on the wallpaper in his mother’s kitchen, contained some youthful pranks — for example, Kürten tucked images of marijuana plants among the flowers. The latest is more serious. It looks decorative from afar, but up close, it’s a beautiful minefield, rife with tiny disquieting images: a handgun, corporate logos and the atomic energy symbol, among others. This iteration, he says, “is about the real world, with its hidden dangers, hidden threats. It’s inspired by today’s events.” A second large-scale work without architecture, Black Mirror (2017), was made from some of Kürten’s many sketches for Perfect World.

Kürten considers Perfect World a bit of a detour but one, he says, that he had to take and that inspired many ideas. “I even have a list of paintings I have to do,” he notes. When asked what he hopes people might take away from his work, Kürten replies, “When I started painting, the idea was to say something all the time. But now, I work with the feeling that I’m not quite sure where I’m going but that I have to go ahead with it. I don’t want to be too obvious.” Whatever people may or may not read into one of his works, the artist adds, its subtlety “allows people to think it’s a beautiful painting.”