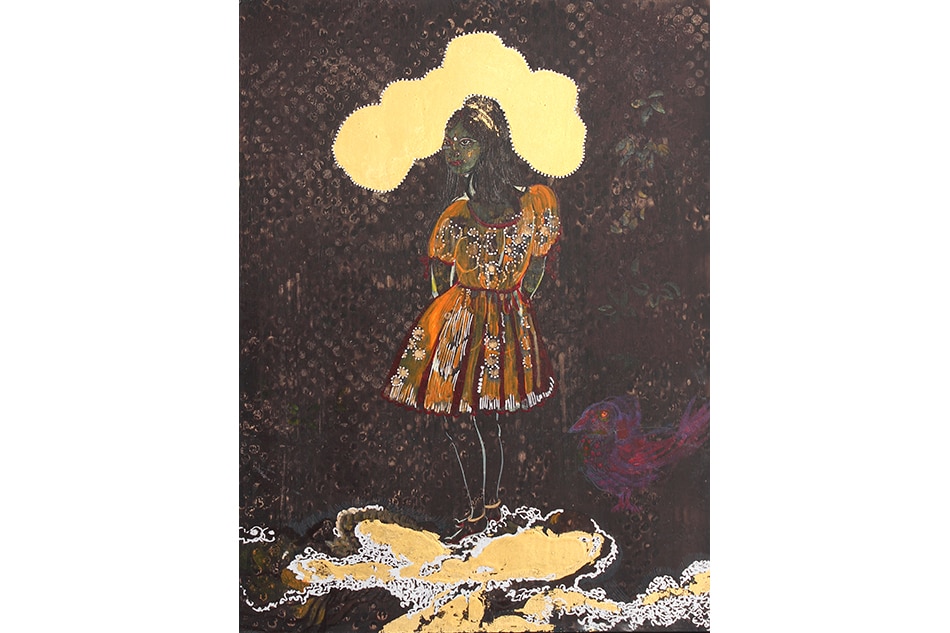

February 13, 2017Rina Banerjee (top, in her studio) is the subject of a show on view at San Francisco’s Hosfelt Gallery through March 4. The exhibition includes the 2012 work, above, whose involved, poetic title is typical of the names Banerjee has given the work seen in this show: Lady of Commerce — hers is a transparent beauty, her eager sounds, her infinite and clamorous land and river, ocean and island, earth and sky…all contained, bottled for delivery to an open hole, a commerce so large her arms stretched wide and her sulfurous halo. All photos by Jeanette May

In Rina Banerjee’s new exhibition “Human Likeness,” on view through March 4 at Hosfelt Gallery, in San Francisco, a crib dangles from a huge cloth-covered dome. At first glance, it looks like a balloon descending with a baby for all to admire and examine. Yet the glass head lying inside the crib has a large black horn protruding from its neck in place of a body, suggesting a creature at once mystical and mutant.

“We wait in anticipation to observe, as parents, relatives, friends, the likeness of the newborn,” Banerjee says of this piece, noting the importance of shared appearances in the way people identify with and care for a child. “If you don’t find likeness to someone, you don’t feel compassion, sympathize. It speaks to the way we associate with or disassociate from groups of people who are not part of our family, as well as our racial group, our social group, our economic group.”

The pieces exhibited in “Human Likeness” — seven richly ornamented sculptural assemblages and a dozen works on paper depicting surreal hybrid figures in strange fairy-tale-like settings — explore ideas of difference and similarity, both psychological and cultural. Since completing her MFA at Yale, in 1995, the 53-year-old Indian-born, New York–based artist has collaged a palette of commonplace tourist items, such as feathers, saris, beads, shells, Chinese umbrellas and porcupine quills, into dazzling, colorful three-dimensional works that can teeter on the edge of gaudy. “The whole conversation about what passes as exotic and what doesn’t is a very interesting one,” says Banerjee, who cross-pollinates her culturally specific materials, which she sources from specialty stores in Koreatown, Chinatown and the garment and flower districts near her studio in Manhattan’s West 30s, as well as from the sprawling online bazaars of eBay, Etsy and Amazon.

Born in Calcutta in 1963, Banerjee moved with her family to London at age three at a time when few Indians were living in the West. Her father’s work as a civil engineer took the family to Manchester and then, when the artist was seven years old, to New York. “There weren’t any sari stores or Indian grocery stores when we first came,” says Banerjee, who accompanied her mother on trips to the garment district to buy fabric to use in sewing her own saris. She frequents these stores now for a range of textiles from Asia and Europe, and says she likes “to find ways of making art that aren’t from an art supply store.”

Privacy: Ruby colored was this night when her eyes failed to…, 2012

A family trip to Virginia Beach was Banerjee’s first experience with overt segregation. “When we went to the beach with our towels, we found one side of the beach was white, the other side of the beach was black,” recalls Banerjee. “They didn’t know what to do with us so they put us right on the ‘color line,’ as they said.” A work on paper made in response to that event is included in the exhibition. It portrays a little pony-tailed girl with a monstrous green head and torso sporting extra appendages who runs scowling through a web of blue droplets and orange lines like an avenging superhero. The 77-word title, offering the viewer a wandering pathway through the slightly hallucinatory terrain, ends with She lanced all ties with magic in her thigh — suggesting the protagonist’s mythical power rather than shame about her unusual skin tone.

This is emblematic of the two-dimensional works on view, dominated by female figures that may sprout wings or horns or multiple heads. One, wearing a grass skirt and lei, seems amphibian and floats in a resplendent otherworldly plasma studded with miniature feminine creatures. “Is that the imagination of this larger figure, or are those smaller figures in the distance?” Banerjee asks. “Is that an angel? Or a baby figure? I love the connection between the conscious and the unconscious that it plays on.” Her paragraph-long titles do more to complicate than clarify her dreamlike narratives.

The artist work on an in-process piece in her studio.

Banerjee learned to draw and paint as a child at home but originally studied science at Case Western Reserve University, in Cleveland, where she received a degree in polymer engineering in 1993. Although she soon switched gears and pursued art, she says her understanding of science informs how she puts together disparate materials, what kind of adhesives she uses, what will stand the test of time. Her large assemblages, comprising hundreds, even thousands of small objects, require painstaking handwork: stringing, wiring, sewing, upholstering.

Banerjee’s inclusion in the 2000 Whitney Biennial put her on the map. Her contribution to the show was a 23-foot-tall and 33-foot-wide installation that came off the wall and seeped onto the floor. Called Infectious Migrations, the piece explored ideas of feminine contamination and transmission through a vast assemblage of incense sticks, Vaseline, an Indian blouse, gauze, fake fingernails and eyelashes, Spanish moss, lightbulbs, latex gloves and red pigment. She has since shown in the quinquennial “Greater New York” show at MoMA PS1 (the Museum of Modern Art’s Queens branch) in 2005 and 2015, and in 2018 she will have her largest solo museum exhibition to date at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, in Philadelphia.

Banerjee will also be included in the art triennial Prospect.4, opening this November in New Orleans. For this, she plans to do another large dome installation in the museum’s two-story entry space. “The parachuted figure is interesting to me in the framework of what’s happening in New Orleans — the political problems, environmental problems and racial tensions,” says Banerjee. “The idea is to use the dome again as a balloon where someone’s being rescued — or rescuing themselves maybe.”