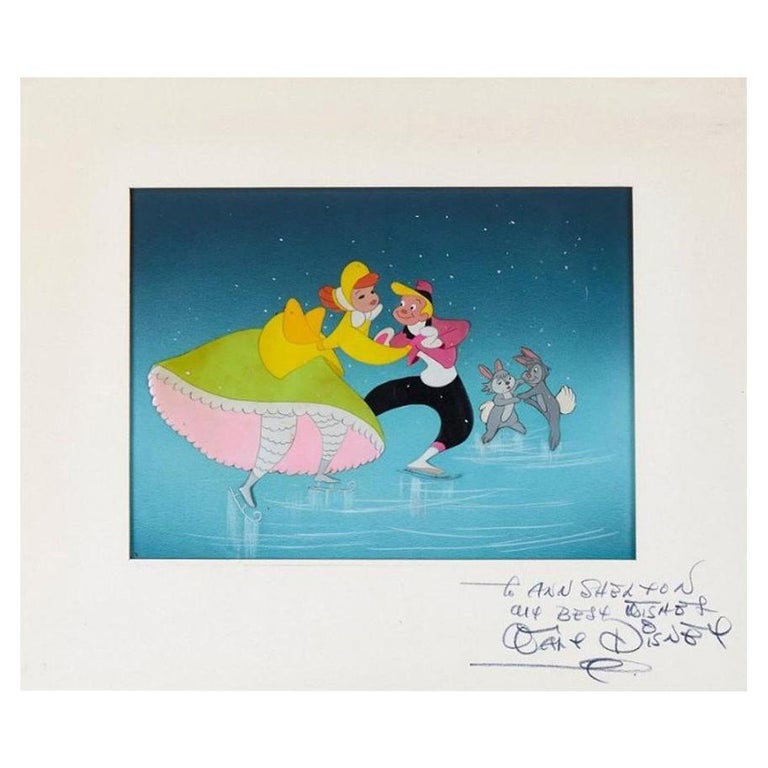

January 30, 2022In 1938, Hollywood dream maker Walt Disney donated a gouache painting on celluloid of two rapacious vultures — a cel from the first Technicolor animation blockbuster, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs — to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The New York Times was snarky. “But is it art?” a critic asked.

The line between high art and popular culture has long been blurry. The Met embraced the crossover early on by accepting Disney’s gift into its permanent collection. Now, it is exploring this hybrid territory in a new exhibition, “Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts.”

The menacing vultures are on view, in a nod to the museum’s first Disney connection, along with 150 other artworks from the Disney archives. These are accompanied by 60 examples of the 18th-century European decorative art that inspired the visual language of such beloved hand-drawn films as Snow White (1937), Cinderella (1950), Sleeping Beauty (1959) and Beauty and the Beast (1991). The show runs through March 6, after which it travels to the Wallace Collection, in London.

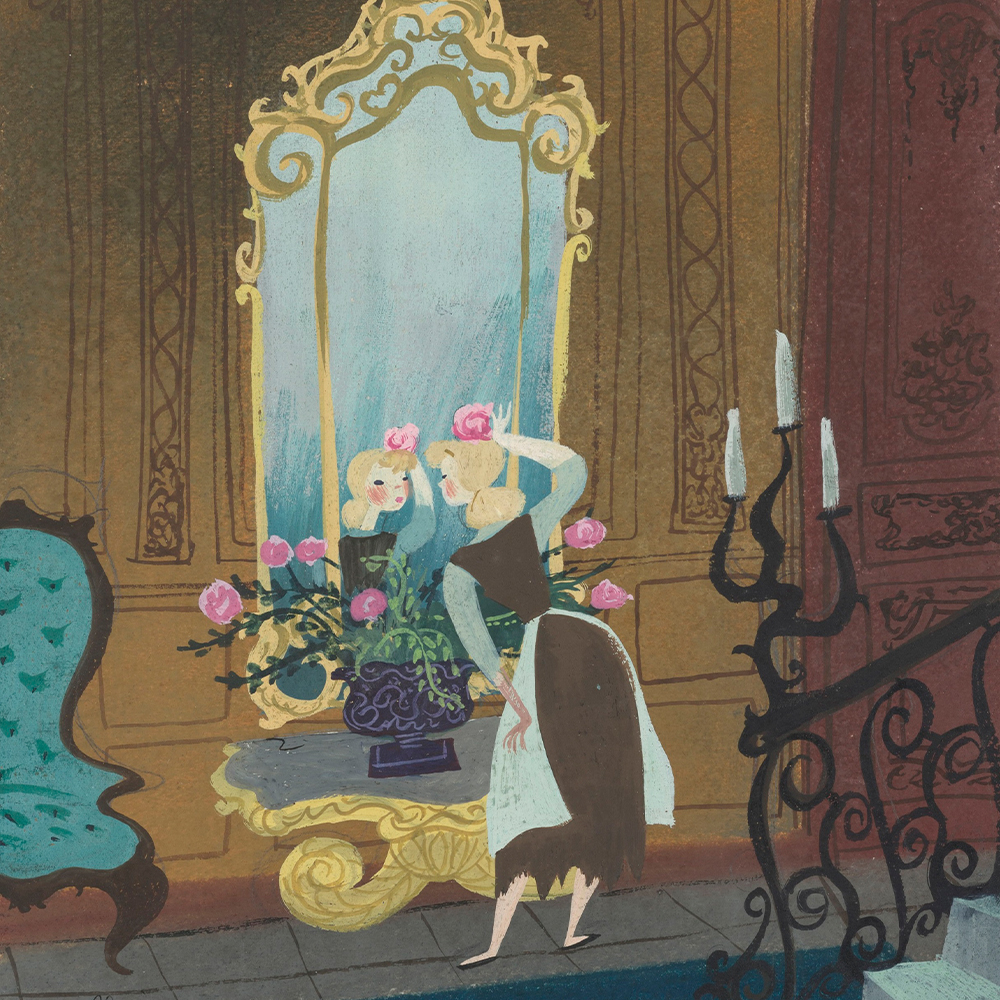

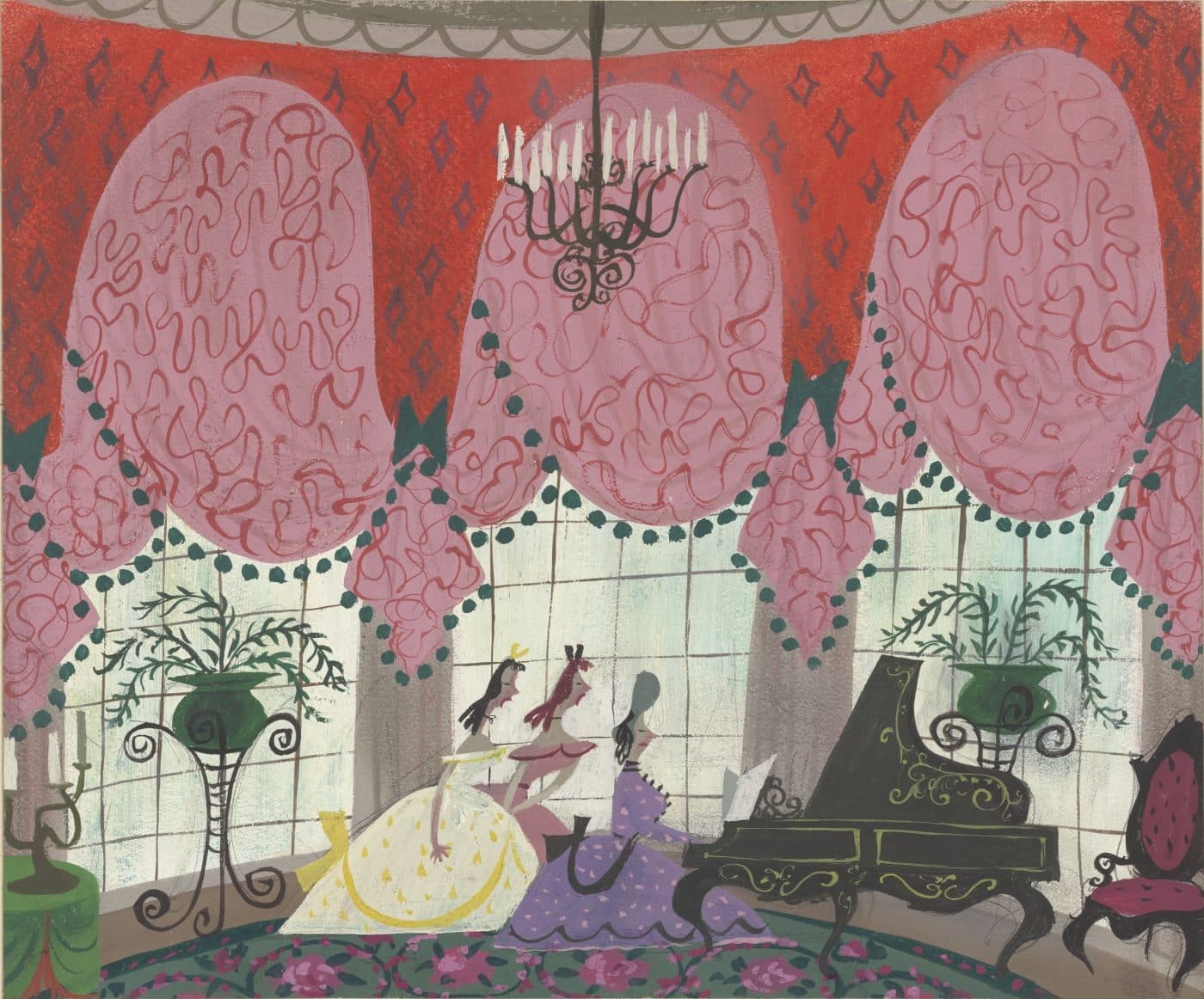

Concept drawings and production art are exhibited side by side with such items as a red velvet settee, gilt-bronze clocks and porcelain figurines, pieces that at one time weren’t museum artifacts either, but household objects, albeit those of the aristocracy. In this way the show illustrates how Disney Studios artists brought European visual culture, particularly 18th-century Rococo tastes, to charming life for the delight of 20th-century American children.

It all makes perfect sense when you think about the glittering chandeliers and gilded chaises in Cinderella’s stepmother’s château or the vast ballroom modeled on the Palace of Versailles’s Hall of Mirrors in Beauty and the Beast, the last of the hand-drawn Disney features before computers transformed the art of animation.

“The genius of Walt Disney and his studio was to have intuited the animation implicit in these ornate furnishings and discovered the technology to bring them to life,” says Wolf Burchard, the exhibition’s curator.

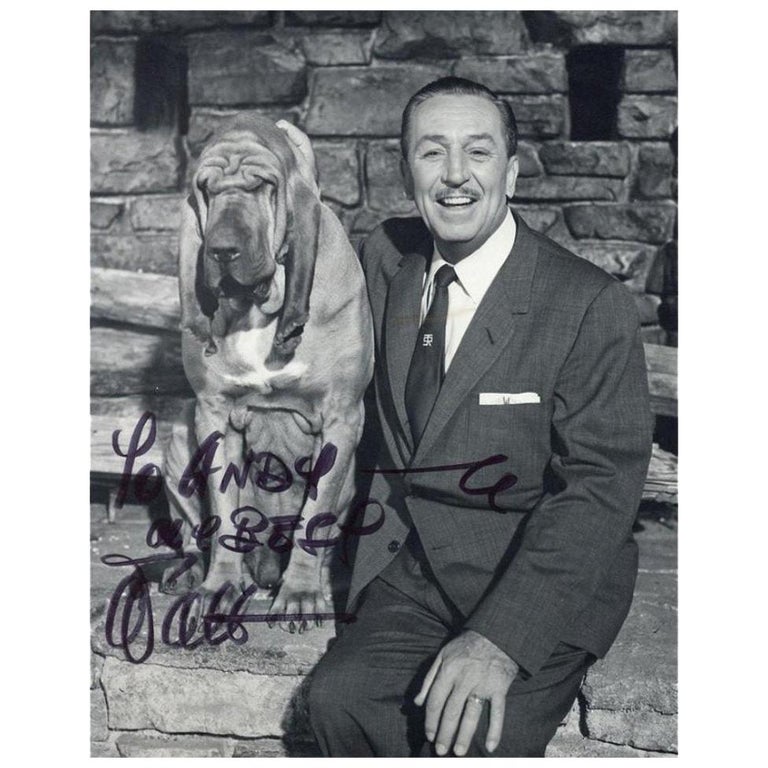

Born in Chicago, Walt Disney (1901–1966) had a modest Midwestern upbringing but became obsessed with European castles and châteaus while serving, at age 17, as a Red Cross ambulance driver in France in the aftermath of World War I. The experience sparked a lifelong passion for fanciful environments, from the miniature dollhouse furnishings he collected and sometimes crafted to animated cartoons, feature-length movies and, eventually, in the 1960s, theme parks.

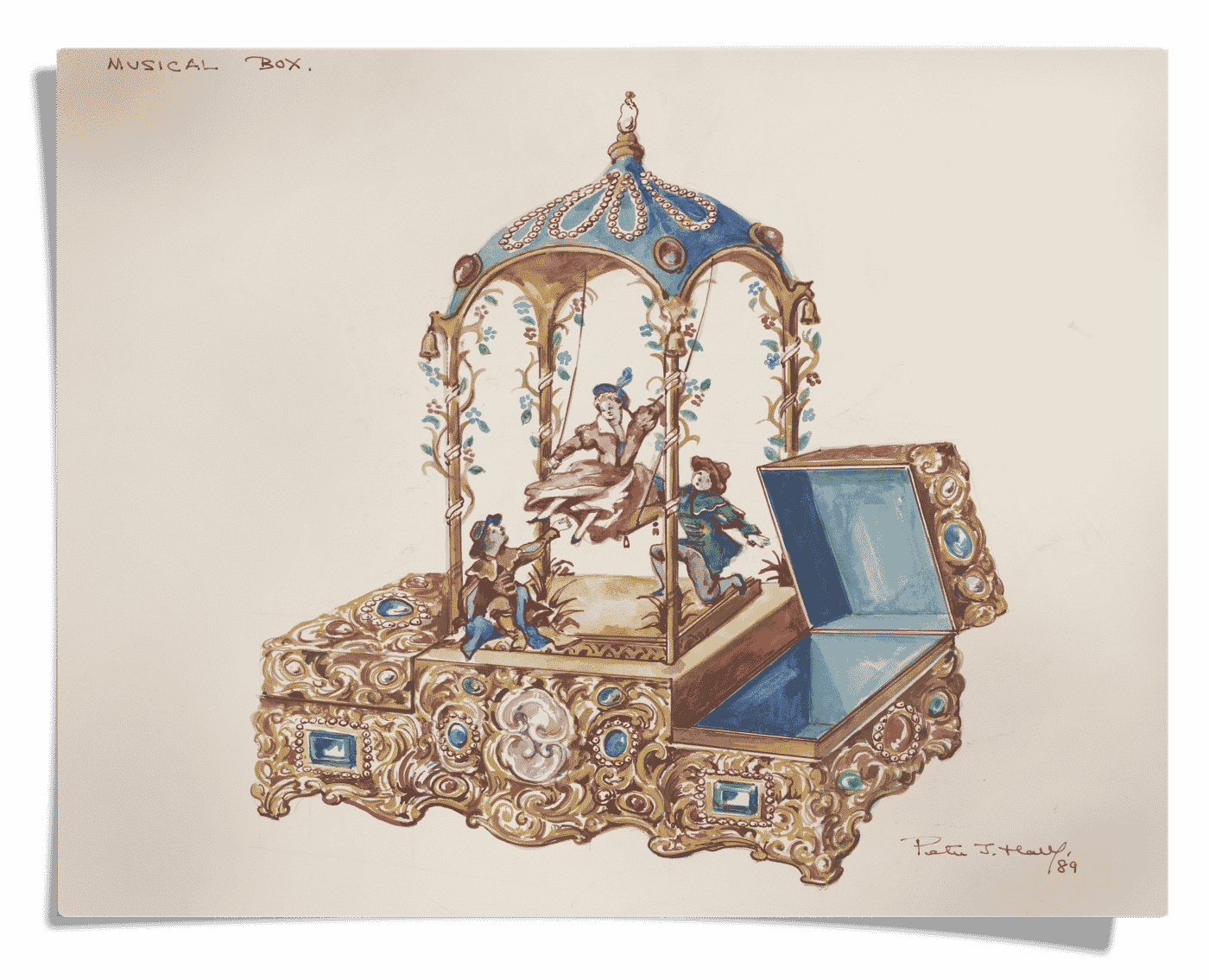

Even before the full-length features of Disney Studios’ mid-century cinematic heyday, whimsical porcelain figurines — represented in the show by several mid-18th-century hard-paste porcelain vignettes from the Meissen manufactory in Germany, including one featuring a piano-playing fox — were brought to life by an early generation of Disney animators in seminal “Silly Symphonies” cartoons like The Clock Store (1931) and The China Shop (1934).

The studios’ artists were known for their painstaking research. In developing a look for Sleeping Beauty, they consulted medieval manuscripts, stained glass and tapestries, including the circa 1500 Unicorn Tapestries from the Met’s collection. Later, the studio sent phalanxes of artists, sketch pads in hand, to 16th-century Loire Valley châteaus and “Mad” King Ludwig II’s Neuschwanstein castle, in Bavaria.

They studied many of the same objects as are on view at the Met, including a circa 1760 Sèvres porcelain piece depicting children looking at a magic lantern — a box containing colored illustrations that was a novelty in its day.

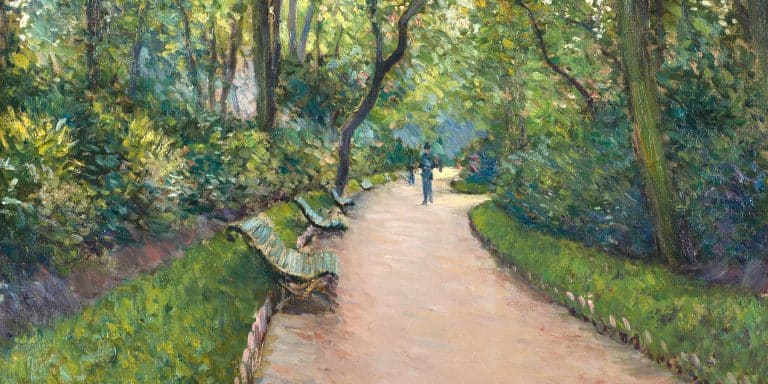

Another inspiration was pastoral paintings, like The Swing, created in Paris around 1788 by Hubert Robert. One of many iterations of a then-popular subject — a girl in a pastel dress on a swing — it boasts a lush background that recalls the classic opening to many Disney films, in which the camera travels through an enchanted forest before zooming in thrillingly on a turreted castle.

A similar painting of the same name, painted a decade earlier by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, was also instructional to Disney artists, who looked to the positioning of the exuberant girl on the swing, the “tilt, rhythm and twist . . . that bring a character and a scene to life,” Beauty and the Beast animator Glen Keane recalls in the exhibition’s audio guide (available on the Met’s website and on Spotify).

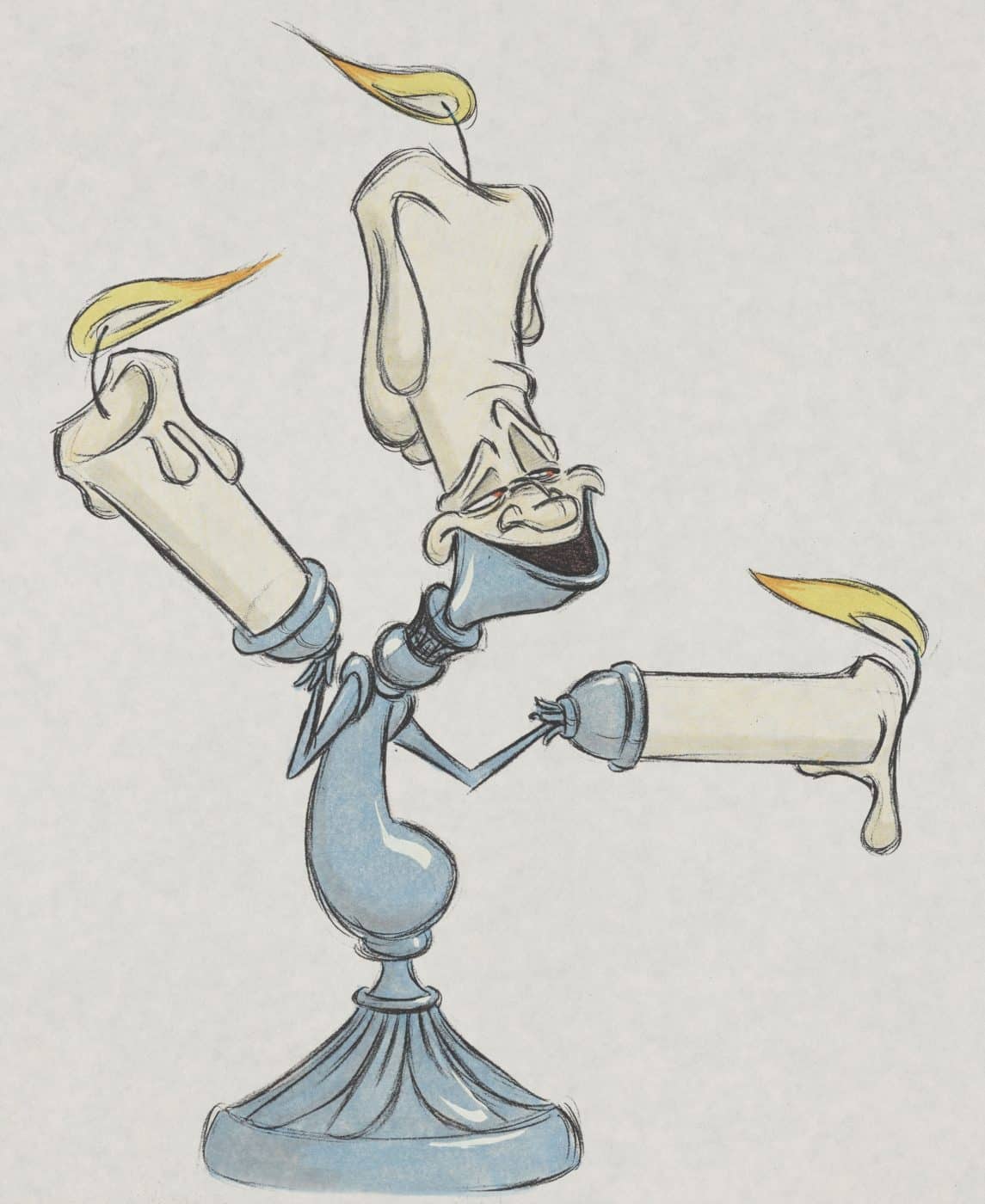

Indeed, the household objects in Beauty and the Beast are anything but inanimate. Concept sketches for Mrs. Potts, the jolly teapot; Lumière, the debonair candlestick; and Cogsworth, the tightly wound clock, are displayed alongside the antique pieces that directly inspired them: early 18th-century Meissen teapots, including one in the form of a bearded man riding a dolphin; sinuous circa 1745 gilt-bronze candlesticks designed by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier; and a circa 1690 oak pedestal clock with tortoiseshell marquetry attributed to André-Charles Boulle.

If the fairy-tale castles at the center of the Disney films and theme parks are a bit of a mash-up, playing fast and loose with historical periods and styles, it scarcely matters. The first bird’s-eye-view rendering of Disneyland, drawn by Herbert Ryman under Walt Disney’s guidance over one weekend in the fall of 1953 as a presentation for potential investors, is juxtaposed in the Met show with two pairs of 20-inch-tall turreted vases made by Sèvres around 1763 in soft-paste porcelain and likely reunited in this exhibition for the first time in history. Like the Disney castles they resemble, the pieces are works of pure imagination, designed for a similar purpose: to encourage their beholders’ own imaginations to run free.

“Both Disney animated films and Rococo works of art are infused with playfulness, delight and wonder, igniting feelings of excitement and awe in their audiences,” says Max Hollein, director of the Met. Age is no barrier to such feelings. As Walt Disney himself famously pointed out, we were all children once.