Items Similar to Turbulent Communication Computer Aided Graphic Drawing by Artist Aldo Giorgini

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 6

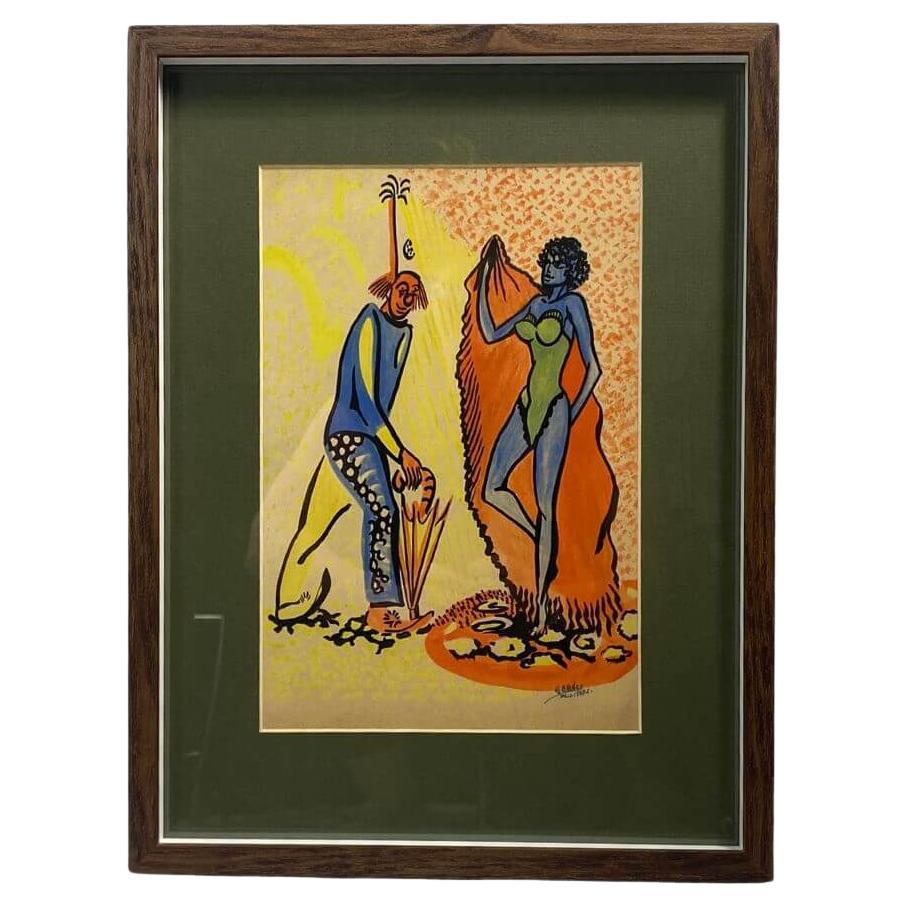

Turbulent Communication Computer Aided Graphic Drawing by Artist Aldo Giorgini

About the Item

This is a rare original "artist's proof" computer-aided drawing by graphic artist Aldo Giorgini. The drawing, entitled "Turbulent Communication", was designed using his "Fields" computer program developed in Fortaran at Purdue University in 1975. The fourth picture in this listing shows the final iteration of this piece as featured in the 1985 publishing of "Computer Graphics-Computer Art" by Herbert W. Franke (notice the rotated black square background). Picture 5 shows Aldo himself in his studio circa 1975. Giorgini is considered by many to be one of the founding fathers of computer graphic art and this piece is a wonderful, one-of-a-kind example of his ground-breaking work.

Artist's process: This piece was created by taking a plot from the original Fields computer design, hand-inking the black areas, creating an electro-static copy of the painting, creating a silkscreen, then printing resulting image as a final serigraph.

A brief background on the artist:

Giorgini was born in Voghera, in the province of Pavia (northern Italy). He was a high school classmate of fashion designer Valentino, who was also a student of design of Ernestina Salvadeo, Giorgini's maternal aunt.

Formally trained by Italian Futurist painter-sculptor Ambrogio Casati, Giorgini stayed on with his mentor as an apprentice, and assisted in the restoration of Classic works by old masters damaged during the Second World War. Simultaneously attending university coursework outside of his work in the arts, Giorgini earned a doctorate in Mechanical Engineering from Politecnico di Torino before travelling to the United States on a Fulbright Scholarship. There, Giorgini earned a second doctorate, this time a Ph.D. in Civil Engineering from Colorado State University, and accepted a professorial position in the School of Civil Engineering at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. He moved to Lafayette, Indiana, on 22 December 1968.

At Purdue University, he won several awards and distinctions as an outstanding teacher of fluid mechanics and engineering mathematics at the graduate and undergraduate levels. He regularly included aesthetics lectures in his engineering courses, saying that "to be technical and scientific does not preclude a concern for the beauty and art of image and form. Architecture and engineering both occupy the same continuum: mathematics can be beautiful, and shapes can be useful."

Once established in this new position, Giorgini resumed his artistic work, combining his technical expertise with computers from his engineering training with his background in the visual arts, thereby becoming one of the first computer artists.

His pioneering computer art was generated on the Purdue University mainframe computer (CDC) and printed onto large Mylar sheets using Calcomp printers. Giorgini would then hand-ink the works of art to complete the works he called examples of "computer-aided art".

This Q & A letter written by Giorgini himself gives interesting insight into his life, artistic methodology, and sense of humor:

Dear Editor,

I hope you will accept my article in letter form. I think this device will allow me a freer hand than a normal article would, and, perhaps, a closer touch with the queries that you expressed in your call for papers.

My art background is, perhaps, somehow unusual if compared to the average American artist. At the age of ten, I was asked to apprentice to Carlo Ingeneri, a now well-known painter and sculptor of Decamere, Eritrea, who, to make a living, was teaching freehand drawing in the school I was attending. Initially my parents paid a fee which was later waived when my work in the shop was worth the instruction I received from the artist. World War II over, in 1949 my family moved back to Italy, where the same circumstance repeated itself. The freehand drawing instructor of the Scientific Lyceum I frequented in Voghera asked me to be his apprentice. Ambrogio Casati (this is his name) is a painter and sculptor who has worked in a number of media and has produced outstanding works which are now in high demand. He had been one of the handful of futurists that survived the ideologic condemnation of fascism and developed in a strong personal style that recalls both the Impressionists (for the subtle use of light) and the Futurists (for the special atmosphere of in fieri of his paintings).

Notwithstanding my dedication (I was spending an average of three hours a day in the studio) and my success in handling the media, I never considered seriously a future in art. The environment of my formative years (a mixture of maternal and paternal influence) had conditioned my order of achievement values roughly in the following order: Saint ? Artist ? Scientist ? Hero ? Builder ? Politician and/or Moneymaker. A realistic assessment of my talents and the crushing conditioning of the above hierarchy made me choose engineering for a career.

Since entering college I have only occasionally produced some artwork, but the dormant interest woke up four years ago, when I started developing a wet technique with enamels and acrylics that took literally two years to control. I call this process chastique (from stochastic technique).* The works done in this technique feature fantastic organic-like forms which, according to the words of Mario Contini, art critic of Eco D'Arte, Florence, Italy, are "characteristically well balanced, refined, and stimulating at the visual-interpretative level. Urging... masses full of meanings Stand out from the background and arise as introductory archetypal data and as emblematic images, either for a free fantastical enjoyment or for an exclusively aesthetical fruition, ad libitum." I still work with this technique now and then, since I think that it is rich with possibilities for visual experiences, albeit I spend most of my time free from professional activities in the direction of computer visualizations.

As it may be suspected, I started using the computer as a scientific tool. In the years 1966-67, while Postdoctoral Fellow at the National Center for Atmospheric Research I worked on numerical simulation of turbulence. The research was very demanding at the visualization level and, therefore, I started playing with the output facilities for the best graphical representation of the results of my research. I made some computer generated movies with the CRT-microfilm facility of NCAR and in the waiting time between one output and the next I made some sequences of didactical nature about Fourier Analysis. Once at Purdue, I had some graduate students in the same field, and I started 'playing around' with some of the computer drawings that were made as illustration of the research done. From here to the purposeful use of the computer as an art tool the pace was very short.

This being the origin of my computer efforts in art, it should not be surprising to discover that the way I use the computer in scientific endeavors has affected my thinking about its use for the production of art. In fluid-mechanic research by computer, the preparation of the computer programs and subroutines has always been seen by me as analogous to the design of laboratory facilities and of the instruments for physico-experimental research. I have called the complete set of programs and routines a 'numerical laboratory' for numerical 'experiments' in fluidmechanics. To be sure the time devoted to the design of the facilities and instruments (programs and subroutines) is of paramount importance, and sometimes one has to go beyond the conventional design for a true invention of instruments and facility parts. No matter how 'intoxicating' this design part, I've always tried never to lose track of the goal of the research: the experiments in fluidmechanics. The same attitude I have devoted to the 'computer visual experiments.' I have designed and invented programs and subroutines, not for their own sake but as components of the 'numerical laboratory' for the 'visual experiments.' You can see that this attitude is the same one that was implied in my mention of the chastique. In other words, in my view, programs and subroutines are the disposable part of the process of art by computer.

The prints that I send you have all been made using drawings generated with the program FIELDS, developed by myself with the help of Dr. W.C. Chen. These drawings (and some others not illustrated here) are the reason why the program was made. Other people may use this program, if they wish, (it has been published in its entirety with explanations for its use) but it must be realized that the 'numerical visual laboratory' called FIELDS, as any other program, is far less than a tool: it is literally a 'programme' with a large number of degrees of freedom for the user, but with a still larger number of degrees of freedom 'frozen in' by the designer. The user must realize that whatever output that program yields, it will reflect more the creative constraints of the designer of the program than those of the user. The user has to bend, to comply with a very general view of visual phenomena, and is bound to produce at best an original on the 'style' of the program, at worst a variation ? imitation of one of the existing outputs.

The word style has been used here with intentional critical connotations: the use of one program will guarantee the development of a 'style' (which some critics may discover as broader than the slogan-type styles which some traditional artists develop with the only non-ostensible purpose of being singled out from the crowd). In my view, this is a cheap way of getting somewhere with a minimum of effort. It is true that the development of a numerical laboratory for visual experiments is justified by the diversity of experiments that can be performed (in other words: let one day of creation be followed by six days of restful, complacent contemplation). But, in my view, these experiments should explore the region delimited by the degrees of freedom of the program, and not describe in detail the minutest variations that lead from one 'original' to the next. If one proceeds in the latter direction, a lifetime of stylistically coherent artistic production is guaranteed to follow the one day of creation.

With the above, dear Editor, I feel that I have implicitly answered several of the questions that you have asked. I will now answer explicitly some others.

"Do you have a final image in mind when your work begins?"

I think that this fundamental question should concern more the behaviorist than the art critic or the artist himself. But the question is asked over and over to any artist. He is, therefore, compelled in the direction

of introspecting himself in order to discover his modus operand!;

of reporting the eventual findings.

While the introspective phase may have its positive influence on the artist's conscious behavior, the explanatory phase may result in deleterious effects, since it may produce cliches that aim more at astounding than at reporting. (A propos, have you seen the recent television documentary by the title "Hello Dali"? Is his theatrical Apparatus just a self-made gilded cage for the dead bird that a miraculous mechanism provides with predictable motion and deja vu melody?)

As an overly simplified model for the modus operandi of an artist I offer, semi-facetiously, the following continuum between the two extremes CeMO and MeMO.

CeMO (purely Cerebral Modus Operand!)—The artist cogitat, ergo est. Visual images are entirely manipulated ... pardon ... mentipulated by the artist's mind and the result of this process is transferred, by any convenient mechanism (the artist's hand, an apprentice, a construction firm, a computer ...), into vulgar material substance (Hello Plato!).

MeMO (Memoriless Modus Operandi)—The artist can react only to what he sees in front of his eyes, without any ability to mentipulate the visual images. The gestures that ensue (hopefully intentional) modify the subject of his visual stimuli.

I think that both conventional artists and computer artists may be found spanning the whole continuum, albeit (non-interactive) computer artists may find themselves closer to CeMO than to MeMO. In my particular case, when I am operating in the computer mode, I tend to fully prefabricate the images mentally and then to render them by computer. The complexity of some of my drawings (see Turbulent Communication) usually creates some doubts about this assertion, since they are very mediate elaborations on moire patterns. Nevertheless it may not be difficult to accept the fact that a relatively large number of experiments performed on the visual effects of moire patterns can give a rather intimate familiarity with the ingredients for their design.

"Could your work be done without the aid of the computer?"

Yes, in a fashion analogous to the one of carving marble with a sponge. Since all FORTRAN instructions could be performed by other techniques, there is no doubt that one could execute the same by calculating and drawing by hand on a Cartesian plane. The difference between the two approaches lies merely in the amount of time required for the execution of the piece. The time constraint is of paramount importance in all endeavors and we are talking here of time ratios that approach some orders of magnitude. The question, nevertheless, is amenable to another interpretation which is more immediate in the following formulation: "Does your work with the computer affect the direction of your results?" This question is germane to the other: "Are your computer works related to your non-computer ones?"

I strongly believe that any one artist using two entirely different processes will achieve two sets of results that are entirely different at the purely visual level. The only liaison between the two sets of outputs is constituted by the aesthetico-formal handling of the visual material and, if at all present, by the motive substratum of the artist's activity ("what makes the artist do it").

Since the purpose of this collection of papers is to present some personal views about (computer) art, I will devote the remainder of this letter, dear Editor, to the exemplification of the above concepts with the particular case of my own works.

The motive substratum of my artistic activity is constituted by the fascination that natural forms have always exerted on me: from the extremely complex organic forms, rich of life-like attributes to the geometric forms of crystalline Formations and to the forms of the invisible fields around us. My mental projection of the visual elements that 'describe' natural forms is constituted not by their 'substance,' their being objects, but by the surfaces that delimit such forms. In other words, I am not interested in recognizable individual objects, but in recognizable forms, be they organic, straight-line geometric, or free-flowing geometric.

From this it follows that the selection of the processes for the rendition of such forms will be conditioned by the forms themselves. Furthermore, the intrinsic capabilities of the process will only focus on the typology of forms amenable to description by the process.

I end my letter, dear Editor, with the mention of my first one-man show. The show was exhibiting computer and non-computer work. The computer work was featuring black and white geometric forms, the non-computer work exhibited multicolor organic-like forms. Obvious contrasts. But to me the remark "They look like the works of two different artists" sounded novel and amusing. The schizoidal element is only superficial (like the one between the artist and the scientist). The 'motor' is one, and so is its formal creative Apparatus.

My best regards,

Aldo Giorgini

West Lafayette, Indiana

September 1975

“In my computer-aided drawings I try to create or to unravel optical illusions by complementing, with my own intervention, what the machine can do best.”

-Aldo Giorgini

“To be technical and scientific does not preclude a concern for the beauty and art of image and form. Architecture and engineering both occupy the same continuum: mathematics can be beautiful, and shapes can be useful.”

-Aldo Giorgini.

FREE HOLIDAY SHIPPING THROUGH THE END OF THE MONTH! BUY BY THE 20TH AND RECEIVE BY CHRISTMAS!

- Creator:Aldo Giorgini (Artist)

- Dimensions:Height: 40.25 in (102.24 cm)Width: 32.25 in (81.92 cm)Depth: 1.5 in (3.81 cm)

- Style:Mid-Century Modern (Of the Period)

- Place of Origin:

- Period:

- Date of Manufacture:1975

- Condition:Print and frame are in excellent condition, there is a small scratch to the plexiglass in the upper right corner (does not cover image).

- Seller Location:Lafayette, IN

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU268038191983

About the Seller

4.7

Vetted Seller

These experienced sellers undergo a comprehensive evaluation by our team of in-house experts.

Established in 1975

1stDibs seller since 2017

272 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 23 hours

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Ships From: Lafayette, IN

- Return PolicyThis item cannot be returned.

More From This SellerView All

- Large Oil and Acrylic on Canvas Abstract Painting by Artist Paul AhoLocated in Lafayette, INWonderful large scale abstract painting by Florida artist Paul Aho. Painting features Aho's distinctive abstract/geometric silkscreen styl...Category

Vintage 1980s American Paintings

MaterialsPaint

- Set of 8 Mid-Century Modern Walnut & Gray Leather Dining Chairs by GunlockeBy Gunlocke, Jens RisomLocated in Lafayette, INFantastic set of 8 model 21C armchairs by the Gunlocke Chair Co. of Wayland, N.Y. Chairs feature solid walnut frames, floating back-rests, new gray leather upholstery and one of the ...Category

Vintage 1960s American Mid-Century Modern Chairs

MaterialsLeather, Walnut

- Mid-Century Modern Industrial 3-Piece Office Set with Desk by Norman Bel GeddesBy Norman Bel GeddesLocated in Lafayette, INThree pieces of iconic mid-century industrial design combine to complete this fantastic home-office suite. - Simmons dresser/desk (by renowned designer Norman Bel Geddes) - Goof Form desk chair - Dazor desk lamp...Category

Vintage 1950s American Mid-Century Modern Desks

MaterialsAluminum, Steel

- Matching Pair of Mid-Century Modern Lounge Chairs by SteelcaseBy SteelcaseLocated in Lafayette, INCharming pair of streel-frame arm chairs built in 1965 by Steelcase Inc. Chairs feature angular, black-painted steel frames, walnut armrests and new saddle-brown vinyl embossed with a classic, western-inspired, paisley motif. With their architectural lines, unique upholstery...Category

Vintage 1960s Mid-Century Modern Lounge Chairs

MaterialsMetal, Steel

- Vintage 1949 Mid-Century Modern Custom L-Shaped Office Desk by George NelsonBy George Nelson, Herman MillerLocated in Lafayette, INThis remarkable piece is a one-off desk/wardrobe/bar/bookcase/storage cabinet custom-designed by George Nelson in 1949 to match his Basic Cabinet Series (BCS) for Herman Miller. The desk was made specifically for a client in the Promontory Apartment Building in Chicago designed by Nelson's associate, and world-renowned architect, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The entire apartment was outfitted in pieces from George Nelson's Basic Cabinet Series for Herman Miller that sat, untouched for nearly 70 years in their original setting! In addition to two aluminium sconces, this piece also features hidden, fluorescent lighting mounted in the upper canopy as a clever solution to Mies van der Rohe's lack of ceiling fixtures. This is a gorgeous, grandiose, and extremely rare piece of design history that will instantly outfit an entire office in striking style! Features: Desk: - Book-matched walnut veneer - Built-in Bar - Built in coat closet/wardrobe - Dual aluminum sconces - Hidden, indirect fluorescent lighting - Silver-plated Herman Miller hardware - Dual "floating" book shelves - Tapered, cantilevered peninsula desk...Category

Vintage 1940s American Mid-Century Modern Desks

MaterialsAluminum

- 1957 Sculpted Pine Mid-Century Modern Bedroom Dresser Suit by Franklin ShockeyBy Franklin Shockey CompanyLocated in Lafayette, INWonderful "Sculpted Pine" bedroom suit by Franklin Shockey. Set features: Year of manufacture: 1957 Highboy Dresser- 35" L x 43" T x 19" D Lowboy Dresser- 57.5" L x 31" T x 19" D Mirror- 43" L x 36" T Nightstand- 21.5" L x 25" T x 16" D Set features solid pine construction and fantastic sculpted design. Lowboy dresser has detachable mirror that can be wall-hanged if desired. A unique dresser...Category

Vintage 1950s American Mid-Century Modern Dressers

MaterialsPine

You May Also Like

- Cheerful Attraction - Drawing - Mixed Media Graphic - from 1968Located in Budapest, HUIn the artwork titled "Cheerful Attraction," a clown steps out from the yellow rain towards the sunlit, elegant woman while holding an umbrella. It's created using a mixed technique ...Category

Vintage 1960s Hungarian Mid-Century Modern Drawings

MaterialsPaper

- Woman Figure Drawing by artist MG, 1998Located in Pomona, CADrawing of a female figure done with watercolor and pencil. Signed M.G. and dated '98. Made with neutral colors and raw lines, this one-of-a-kind drawing depicts a woman posing with...Category

1990s American Drawings

MaterialsPaper

- Framed Drawing by Mexican Artist José Luis CuevasBy José Luis CuevasLocated in Atlanta, GAPencil drawing on paper by José Luis Cuevas (Mexican, b.1934). Entitled "La Esperanza". The work is signed right center and dated 20 Dic. 60 lower right, Silvan Simon Gallery label and inscribed title verso. Sight is 11" by 8.5". With frame is 15" by 19". José Luis Cuevas was a prominent member of the Generación de la Ruptura (Breakaway Generation), who first challenged the then dominant Mexican muralism movement. He remains a distinguished and controversial artist who is known for depicting the darker side of life and the debasement of the human society with often shocking images. He is also known for being an advocate against creating art purely for commercial gain. Provenance: this group of the work on paper by Cuevas is from a collection purchased in 60s from Silvan Simone Gallery, Los Angles, CA. The The Silvan Simone Gallery was founded in 1958 by Silvan Simone, an former co-owner of the Florentine Gallery in Pacific Palisades. Between 1959 and 1967, the gallery showed artists such as Lee Mullican, Gordon Wagner...Category

Vintage 1960s Mexican Modern Drawings

MaterialsPaper

- Framed Drawing by Mexican Artist José Luis CuevasBy José Luis CuevasLocated in Atlanta, GAInk on Paper fragment by José Luis Cuevas (Mexican, b.1934) laid on cream woven paper and framed. Inscribed "Yo Mutilado" and it is faintly signed and dated Oct 27 - 60 upper right. Silvan Sloane Gallery Los Angeles, CA label affixed verso with the titled "Auto Retrato" (Self Portrait). Sight is 14.5" x 9.5". With frame -18.5"by 24.5". José Luis Cuevas was a prominent member of the Generación de la Ruptura (Breakaway Generation), who first challenged the then dominant Mexican muralism movement. He remains a distinguished and controversial artist who is known for depicting the darker side of life and the debasement of the human society with often shocking images. He is also known for being an advocate against creating art purely for commercial gain. Provenance: this group of the work on paper by Cuevas is from a collection purchased in 60s from Silvan Simone Gallery, Los Angles, CA. The The Silvan Simone Gallery was founded in 1958 by Silvan Simone, an former co-owner of the Florentine Gallery in Pacific Palisades. Between 1959 and 1967, the gallery showed artists such as Lee Mullican, Gordon Wagner...Category

Vintage 1960s Mexican Modern Drawings

MaterialsPaper

- Framed Drawing by Mexican Artist José Luis CuevasBy José Luis CuevasLocated in Atlanta, GAInk and watercolor on Paper by José Luis Cuevas (Mexican, b.1934). Featuring characters from a story line inscribed lower left as the following (see ...Category

Vintage 1960s Mexican Modern Drawings

MaterialsPaper

- Expressionist Crayon Drawing by Bauhaus Artist Hans KesslerBy Hans KesslerLocated in New York, NYCrayon drawing of a 1920s German theatrical scene by Bauhaus Artist, Hans Kessler. Hans Kessler was a student at the Bauhaus Dessau and studied under B...Category

Early 20th Century German Modern Paintings

MaterialsCrayon