October 30, 2017Anni Albers rose to fame in the mid-20th century with her iconoclastic graphic weavings, many of which are in a new show at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. Above, she’s seen in a 1937 Helen M. Post photo in the weaving studio at Black Mountain College, where she and her husband, artist and color theorist Josef Albers, taught (portrait by Helen M. Post © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017). Top: Red and Blue Layers, 1954 (photo by Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017).

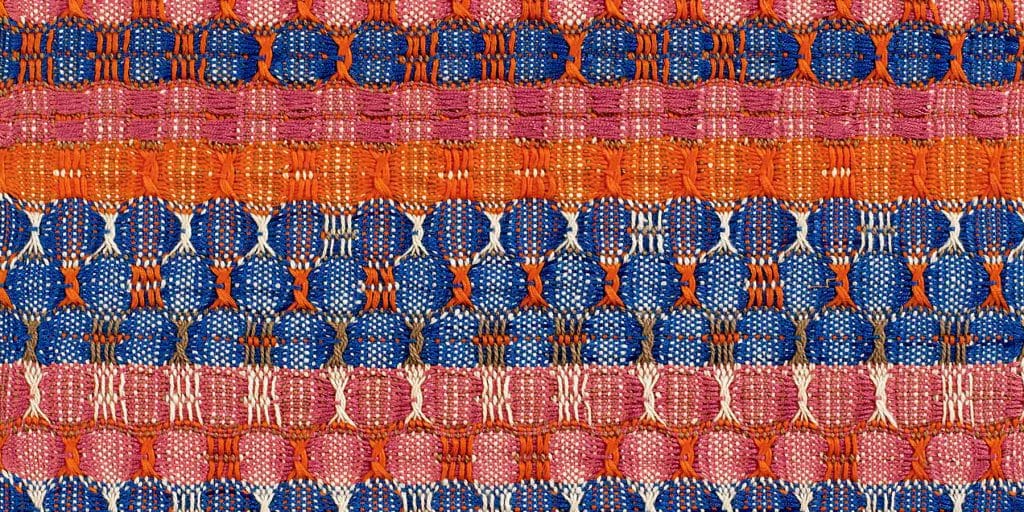

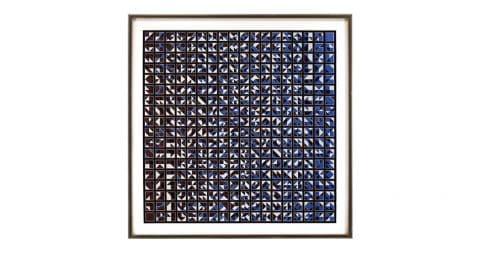

Looking at Anni Albers’s weavings can be a dizzying experience. In Variations on a Theme (1958), she used cotton, linen and plastic to create simple grids, but then, at intervals, she twisted multiple strands of thread around thick plastic warps in formations that resemble elegant double helices. The colors are cream and shades of brown, with touches of orange. Yet as mesmerizing as such pieces are, her art represents only a fraction of her achievement. In addition to being one of the most important textile artists of the 20th century, she was a designer, writer and teacher.

Through all these channels, she left an indelible mark on the art world, and there’s now a resurgence of interest in her modernist legacy. A new edition of her seminal text On Weaving was just published by Princeton University Press. And this month a major exhibition, “Anni Albers: Touching Vision,” opened at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. (It’s up through January 14.) The show includes her weavings with abstract motifs, examples of her commercial fabric designs, the prints she made later in life and even some idiosyncratic jewelry designs.

“Anni’s reputation is well-known, and now weaving has become huge in contemporary art,” explains Brenda Danilowitz, chief curator of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, in Bethany, Connecticut, which lent numerous pieces to the exhibition in Bilbao. “Today there’s a blurring of the line between art and craft, which Anni would have appreciated, because she did not like that line.”

Study for Unexecuted Wallhanging, 1926, is a highlight of the Guggenheim Bilbao show, which runs through January 14. The work is part of the nine-print “Connections” portfolio she released in 1984. Photo by Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

Anni Albers was born Annelise Fleischmann in 1899 to a well-to-do Jewish family in Berlin. (She died in Connecticut in 1994.) Her mother expected her to marry and raise children, but she wanted to be an artist. Her father, who owned Trunck & Co., a successful furniture business, encouraged her dreams.

With his support, she studied at the School of Applied Art in Hamburg and then attended the Bauhaus, the utopian workshop founded in Weimar in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius. The school envisioned a unity of art and design, with the goal of training designers and artisans who could create objects both functional and artistic for mass production. The result was an aesthetic (particularly in architecture) characterized by geometric forms, minimal ornamentation and primary colors.

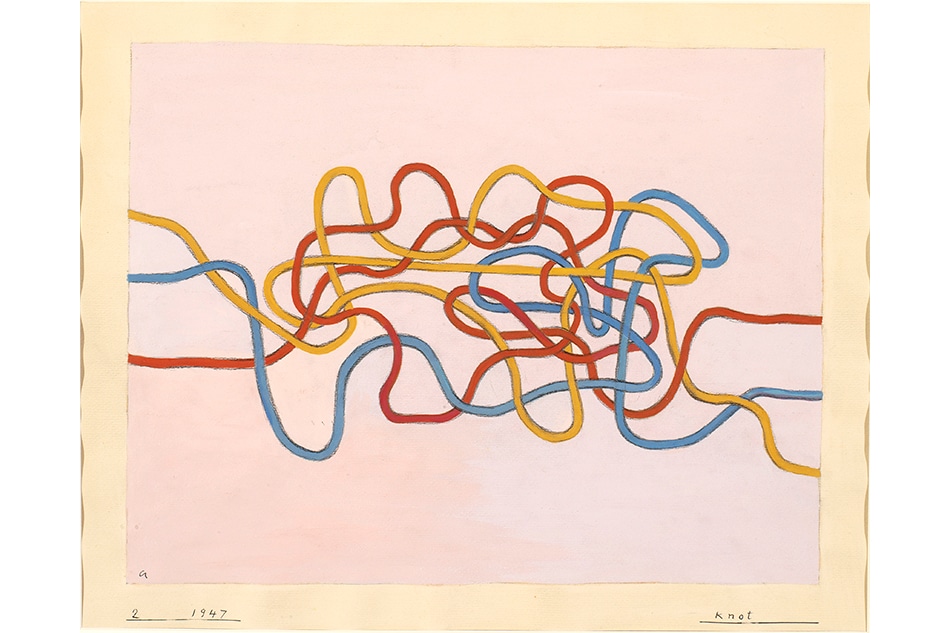

At the Bauhaus, where women’s choices for study were limited, the aspiring artist ended up in the weaving workshop. Although she initially perceived the discipline as unserious, once she had a thread in hand, she was obsessed. “I heard Paul Klee speak, and he said to take a line for a walk, and I thought, ‘I will take thread everywhere I can,’ ” she once told Nicholas Fox Weber, executive director of the Albers Foundation.

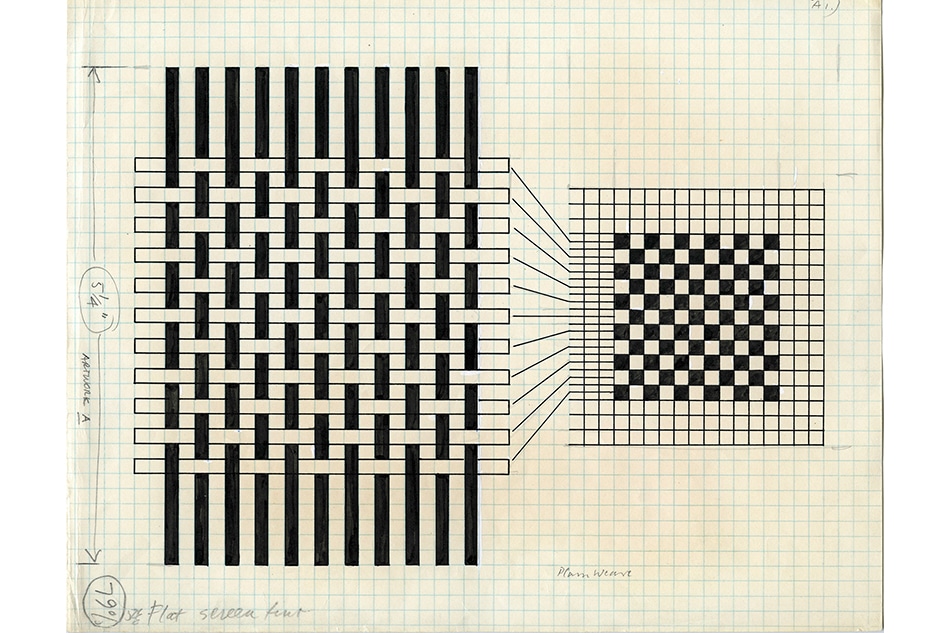

“She was very cerebral,” says Danilowitz, who knew the artist personally, “and weaving is very technical. It’s a lot like engineering, so it was a natural fit for her.” The Bilbao exhibition includes several of her black-and-white mathematical grid diagrams for weavings, including checkerboards in various scales and houndstooth-like patterns.

At the Bauhaus, Anni met and married fellow student Josef Albers, who would later become a celebrated color theorist and painter. His “Homage to the Square” paintings, which explored the relationships between colors, are now considered modernist masterpieces, and his 1963 book Interaction of Color is an essential text on color theory. After graduating in 1930, Anni and Josef both became teachers at the Bauhaus, but when the Nazis came to power, the school was shut down. In 1933, fleeing the Nazis, the couple emigrated to the U.S., where they both became teachers at Black Mountain College, in North Carolina.

Composed of a drain strainer and paper clips, this 1940 necklace, one of the designer’s rare jewelry pieces, is displayed at the Guggenheim Bilbao as well. Photo by Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

Black Mountain, which rejected educational norms and was known for its free-spirited atmosphere, produced many luminaries of modern American art — among them Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly, both students of the Alberses’. In addition to teaching, Anni continued her own artistic practice, making what she called “pictorial weavings”: abstract wallhangings having the same formal qualities as a painting. “She wanted to be recognized as an artist,” Danilowitz says. On view in Bilbao are many of her pictorial weavings, such as Hanging, designed in 1926 and executed in 1967, in which irregular stripes are interrupted by solid rectangles at varying intervals.

The Alberses were fascinated by Latin America even before they crossed the Atlantic, so from North Carolina they made numerous road trips to Mexico and Peru to collect pre-Columbian art. (An exhibition of Josef’s photographs from their trips, “Josef Albers in Mexico,” opens at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City in November.)

The influence of the ceramics and textiles the couple discovered in their travels is clear in Anni’s work. She referred to the weavers of ancient Peru as her “great teachers,” a statement borne out by the Bilbao exhibition, which includes several fragments of pre-Columbian cotton weavings from the Alberses’ collection. Their patterns — zig-zags, maze-like designs and simplified faces — made their way into her textiles, such as Two (1952), in which two colors form a labyrinth.

Yet her approach to weaving was unorthodox. She incorporated unusual materials such as cellophane and metallic thread. She intertwined linked threads in innovative ways and added knots as artistic elements, as in “Dotted” Weaving (1959). She created studies using corn kernels, grass, twisted paper, lines made with a typewriter and pin pricks. Many of her weavings were inspired by script, such as Haiku (1961) and Code (1962), which both suggest lines of writing. Also on display in Bilbao are her jewelry designs, including a necklace made from a drain strainer and paper clips. After decades of such experimentation, in 1949, she became the first textile artist to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York.

In the late ’50s, Anni began publishing books: On Designing, in 1959, and On Weaving, in 1965. To this day, On Weaving is hugely popular. Her writing has been widely hailed as graceful and logical. “There was clarity and integrity in everything she did, from her art to her teaching to her writing,” says Billie Tsien, of Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects (currently designing the Barack Obama Presidential Library, in Chicago), who is also a professor and considers Anni Albers a role model.

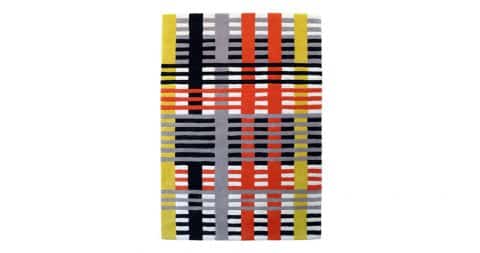

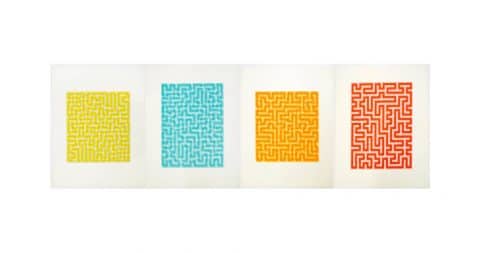

The screen-print Study for a Nylon Rug, 1983, is also included in the “Connections” portfolio, which features work created between 1925 and 1983.

In addition to her art pieces, Anni designed many functional textiles for mass production. In 1949, Gropius commissioned her to create fabrics for the Harvard dormitories he designed. Shortly afterward, she was commissioned to design fabrics for the furniture company Knoll.

In her 60s, when it became difficult for her to operate a loom, Anni turned her energies to making prints. These often depicted the enmeshed threads that captured her imagination, as in the orange and black screen-print Connections — Study for a Nylon Rug, 1983. Her “Connections” print portfolio, on view in the Bilbao show, comprises a series of bold, graphic patterns she developed and then produced variations of from 1925 to 1983. “It shows the trajectory of her entire career in a handful of prints,” says Manuel Cirauqui, curator of the exhibition.

The portfolio includes the 1983 Study for an Unexecuted Wall Hanging, a grid illuminated by bright red and yellow lines that give the piece a distinctly Bauhaus sensibility. “She never used the canonical techniques,” Cirauqui observes of Anni’s prints. “She always wanted to mess around, mixing together things like watercolors and screen-printing.”

Beyond the increased recognition of weaving as an art form, another reason for the renewed interest in Anni’s work is that art history has now turned its lens on women artists who were previously overlooked. This is evidenced in such exhibitions as this year’s “Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction” at MoMA, in which Anni’s textiles appeared. Her impact has long been overshadowed by that of her husband, Danilowitz observes. The Alberses worked separately, collaborating only on Christmas cards and Easter eggs.

“But the fact of her being a woman,” Danilowitz says, “is much less important than the incredible things she did.”