December 9, 2018On view through February 10, 2019, at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, “Tutto Ponti: Gió Ponti, Archi-Designer” brings together an unprecedented volume of works from the modern master’s 0euvre. Top: The show displays pieces of Ponti’s furniture against large-scale images depicting spaces he designed (photo by Luc Boegly). All photos © Gio Ponti Archives, Milan, unless otherwise noted

Dubbed “the godfather of Italian design,” Gió Ponti (1891–1979) established Italy as a cradle of design ingenuity in 20th-century Europe. Now, the amazingly prolific Italian architect, furniture and industrial designer, painter, author, teacher and magazine publisher is getting long overdue recognition in “Tutto Ponti: Gió Ponti, Archi-Designer,” a new exhibition on view at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris through February 10, 2019.

Curated by an all-star team of Ponti experts, including the maestro’s great-grandniece Sophie Bouilhet-Dumas, the show was designed by French architect extraordinaire Jean-Michel Wilmotte in collaboration with graphic designer Italo Lupo. “From the forest of possible choices for exhibitions this autumn, paying tribute to Giò Ponti seemed the most obvious,” the museum’s director, Olivier Gabet, writes in his forward to the fine catalogue.

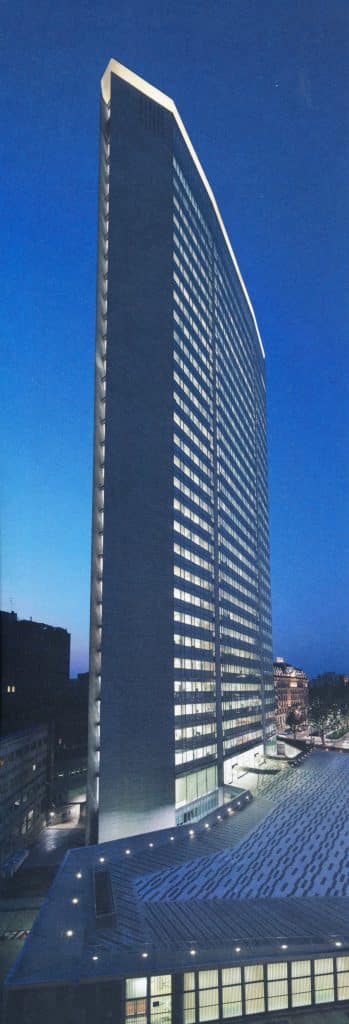

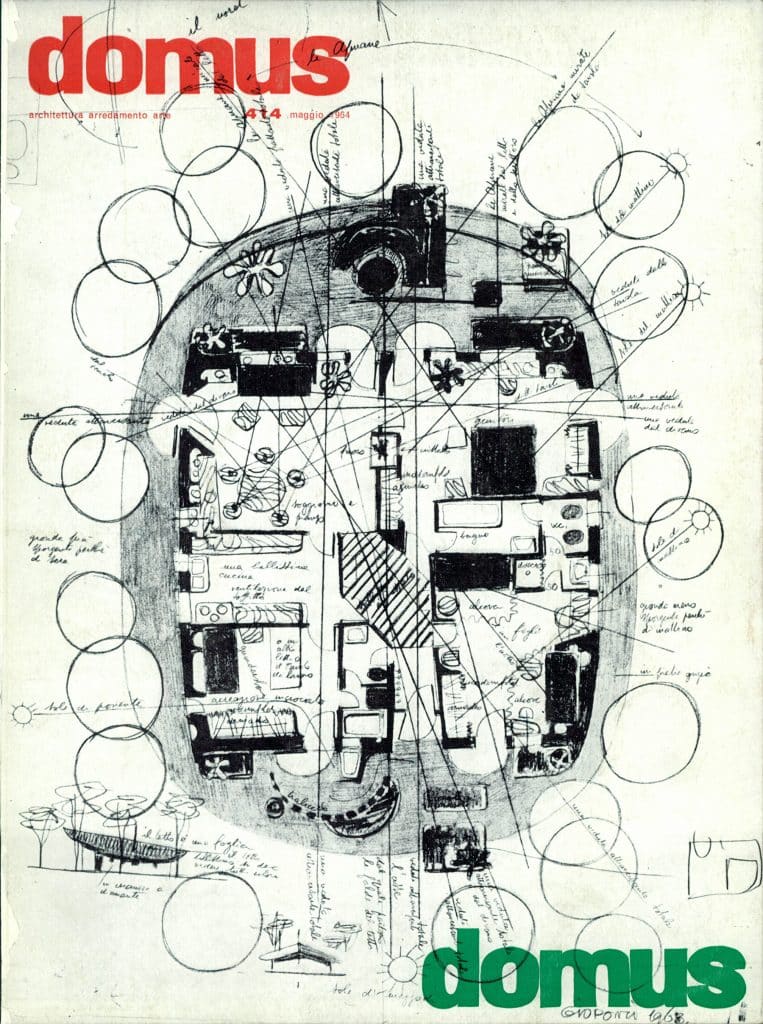

Ponti, based in his native Milan, also worked in Paris, Caracas, Hong Kong and the U.S. during a career that started in 1921 and spanned six decades. His extraordinary output ranged from the super-sleek Aero teapot, for French silver and jewelry firm Christofle, to neoclassical porcelain for Richard Ginori to glassware for Venini and Fontana Arte to innovative furniture for Cassina to such landmark buildings as Milan’s slim and graceful Pirelli Tower (1956-60). In 1928, he also founded the influential monthly design magazine Domus, which publishes to this day.

That long career is represented in the Paris exhibition by a cavalcade of drawings, photos and color illustrations garnered from such sources as universities, cathedrals, apartments and homes and accompanied by a plethora of the furniture and decorative objects he conjured up to fill those spaces.

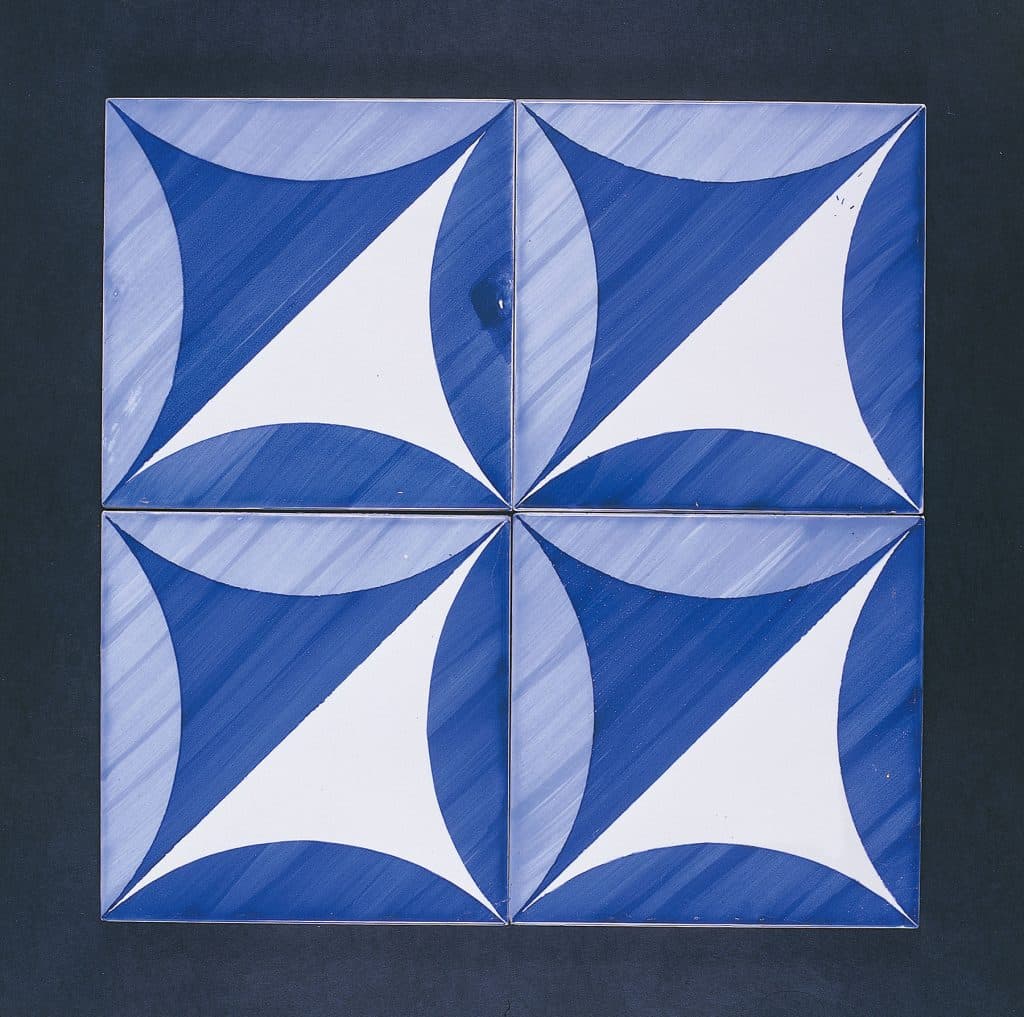

Featured in the exhibition are furnishings and ceramic tiles from Hotel Parco dei Principi, in Sorrento, on Italy’s Amalfi Coast, which Ponti designed in 1960. The catalogue reveals that he “implemented his conception of the hotel as a comprehensive work of art.” Photo by Luc Boegly

“Rome has hills, Naples has islands, the sea and Vesuvius, but Milan — we got nothing,” Ponti says in a short film from 1961 that’s included in the exhibition. He is explaining the impetus for his proposal that year to build rows of skyscrapers surrounded by parks and modernist houses in the city and goes on to theorize: “Skyscrapers work best when they are close together.”

Although that scheme was never realized, Ponti designed more than 100 buildings. In addition to the Pirelli Tower, these include 1970’s lacy Gran Madre di Dio cathedral, in the southern Italian city of Taranto; and the Denver Art Museum, from 1971, known for its glass-tile-clad, fortress-like facade. Currently undergoing a $150 million renovation, the museum is Ponti’s only completed structure in the U.S.

He also designed 10 Milan residences in a new architectural style based on a typical Italian home, which he called casa tipiche, and produced stunning villas that he deemed casa all’Italiana, the Italian House, because they represented Italian-style luxury. One exemplar of this latter category is the Villa Planchart, in Caracas, Venezuela, where soaring rooms rise to color-blocked or colorfully striped ceilings and light floods in through seemingly countless glass windows, both large and small. Described as an “abstract sculpture,” the house is set in a tropical garden, and its facade is dramatically lit at night. An interior portion is reproduced as one of six period rooms featured in the show.

A 1957 photo of Ponti’s iconic Superleggera chair shows a young boy lifting it with one hand, to demonstrate its lightness.

Other rooms come from Ponti’s first office building, for the Montecatini chemical group; the University of Padua; the Hotel Parco dei Principi, in Sorrento, on Italy’s Amalfi Coast; and L’Ange Volant, his first foreign and his first residential commission, for Tony Bouilhet, director of Christofle.

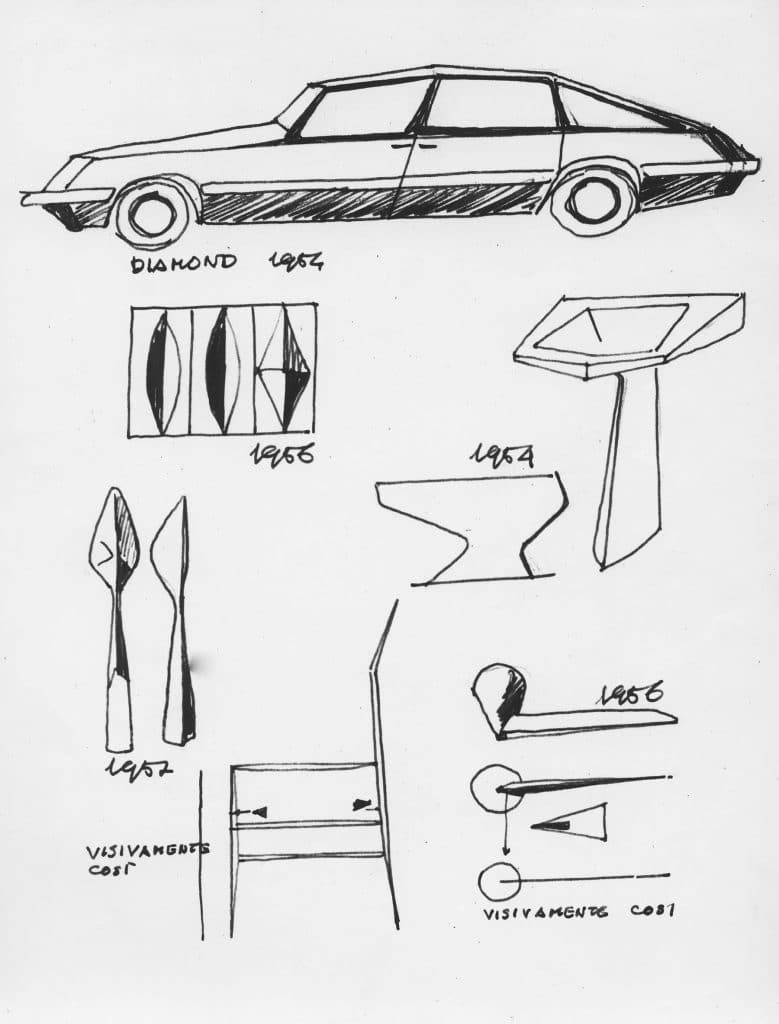

Ponti is perhaps best known to 1stdibs fans for his prolific, inventive furniture designs. Take his bed dashboard, from 1948. An example of his “furniture with function,” this headboard has moveable electrified panels equipped with niches to hold such items as books and radios, so the user has everything at hand.

For the kitchen, Ponti designed a revolutionary espresso machine, La Cornuta, also from 1948. His Leggera and Superleggera chairs, created for Cassina in the 1950s, were inspired by a simple 19th-century model with a woven-straw seat and ladder back. He spent almost a decade perfecting the Superleggera, also known as model 699. Weighing less than four pounds, it became a postwar icon and a symbol of Italian design’s craft tradition. A photo included in the exhibition shows a young boy dangling it high with one hand. Then there’s Ponti’s la casa entro l’armadio, or house in the wardrobe: A sort of pre-Ikea furniture system whose pieces fit into one crate, it was designed to meet the furnishing needs of young couples in Italy in the years following World War II.

A re-creation of Ponti’s own home, on the eighth floor of a building he designed in the mid-1950s on Milan’s Via Giuseppe Dezza, shows off not only furniture but a family portrait. Photo by Luc Boegly

In 1956 and 1957, Ponti designed a nine-story residential building on Milan’s Via Giuseppe Dezza that became in effect a Ponti headquarters, housing his architectural office, his studio and the Domus editorial offices. On its eighth floor, he created the spacious apartment (one room of which is re-created in the exhibition) in which he and his family lived what he called a “transparent” lifestyle, with maximum open space. An emblematic photo shows Ponti and his wife, Giulia, at home: he, relaxed in his sloping Distex armchair; she, firmly straight in a simple seat resembling the Superleggera.

The exhibition’s comprehensive catalogue is worthy of its subject. It covers Ponti’s 60-year career with photos, detailed drawings and color illustrations, including ones depicting rare pieces made when he was employed by Ginori, the storied Italian porcelain manufacturer where Ponti became artistic director at just 32, in 1923.

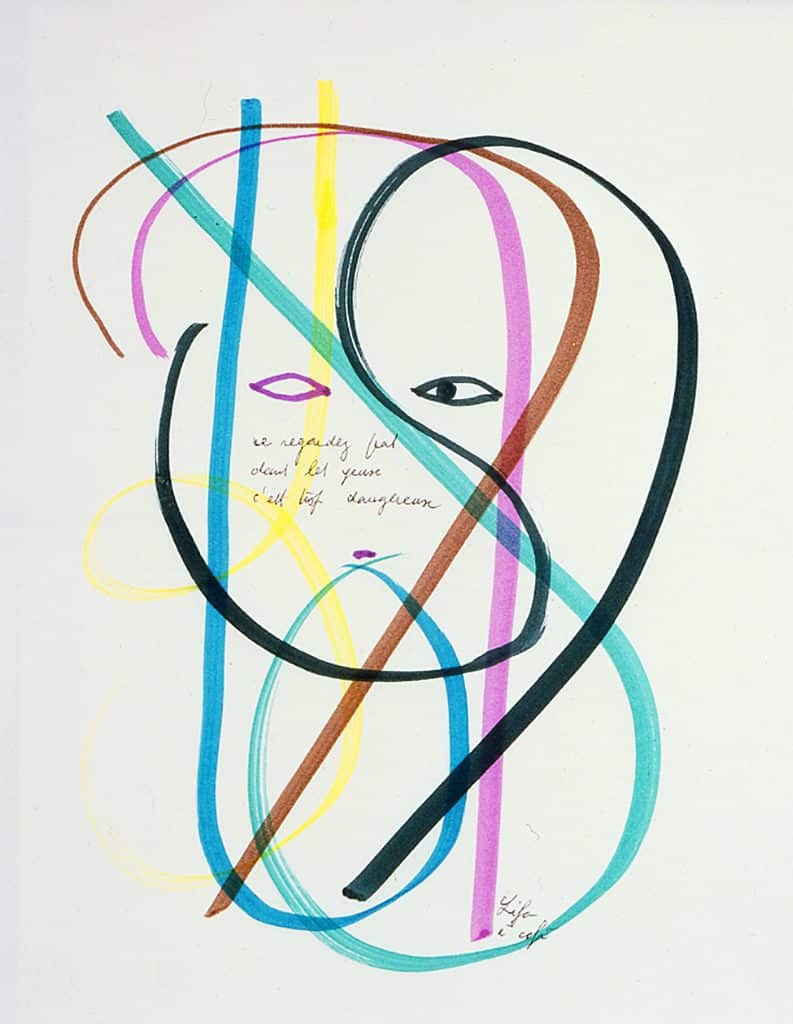

“In 1925, my grandfather discovered Ponti at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs at the Invalides,” says co-curator Bouilhet-Dumas, speaking of Christofle’s Tony Bouilhet. “My grandfather noticed this young man making sketches and speaking to the artisans” at Ginori’s booth in the Italian pavilion. “Ponti always wore a luminous light blue jacket, in contrast to Parisian architects in their black overcoats. My grandfather invited him to dinner at [celebrated cabaret-restaurant] Le Boeuf sur le Toit and introduced him to the Parisian life — Jean Cocteau, André Derain, Man Ray, Paul Valéry.

In another 1957 image, Ponti and his wife, Giulia, are seen at ease in their apartment on Milan’s Via Giuseppe Dezza: he, in his Distex armchair; she, in a Superleggera seat.

“They became great friends,” Bouilhet-Dumas continues, explaining that Ponti would go on to build the Bouihet family’s country house near the Golf de Saint-Cloud. “The area was known as a terrain modernist, because Le Corbusier had built a house there for the brother of Gertrude Stein, and Auguste Perret, who produced prefabricated cement, built another villa there.” The home Ponti designed for the Bouilhets was L’Ange Volant, “and when Ponti’s niece Carla Borletti came to visit the building site,” Bouilhet-Dumas explains, “she met Tony Bouilhet, they fell in love and got married. And that is how our family became Italian.

“My grandparents lived in that house of Gió Ponti,” she goes on, “and there was a small door leading to our house next to theirs. So I grew up steeped in the special spirit of a Ponti-designed space.” Bouilhet-Dumas likens her childhood home to “a temple that sheltered our most profound thoughts, a space for art and reading. And not only was it a comfortable house but a house to comfort you,” she says, highlighting still another aspect of Gió Ponti’s design genius. “In English, it’s called cocooning.”