May 2, 2021Giovanni Ponti (1891–1979), better known by his nickname Gio, was arguably the most important figure in 20th-century Italian architecture and design.

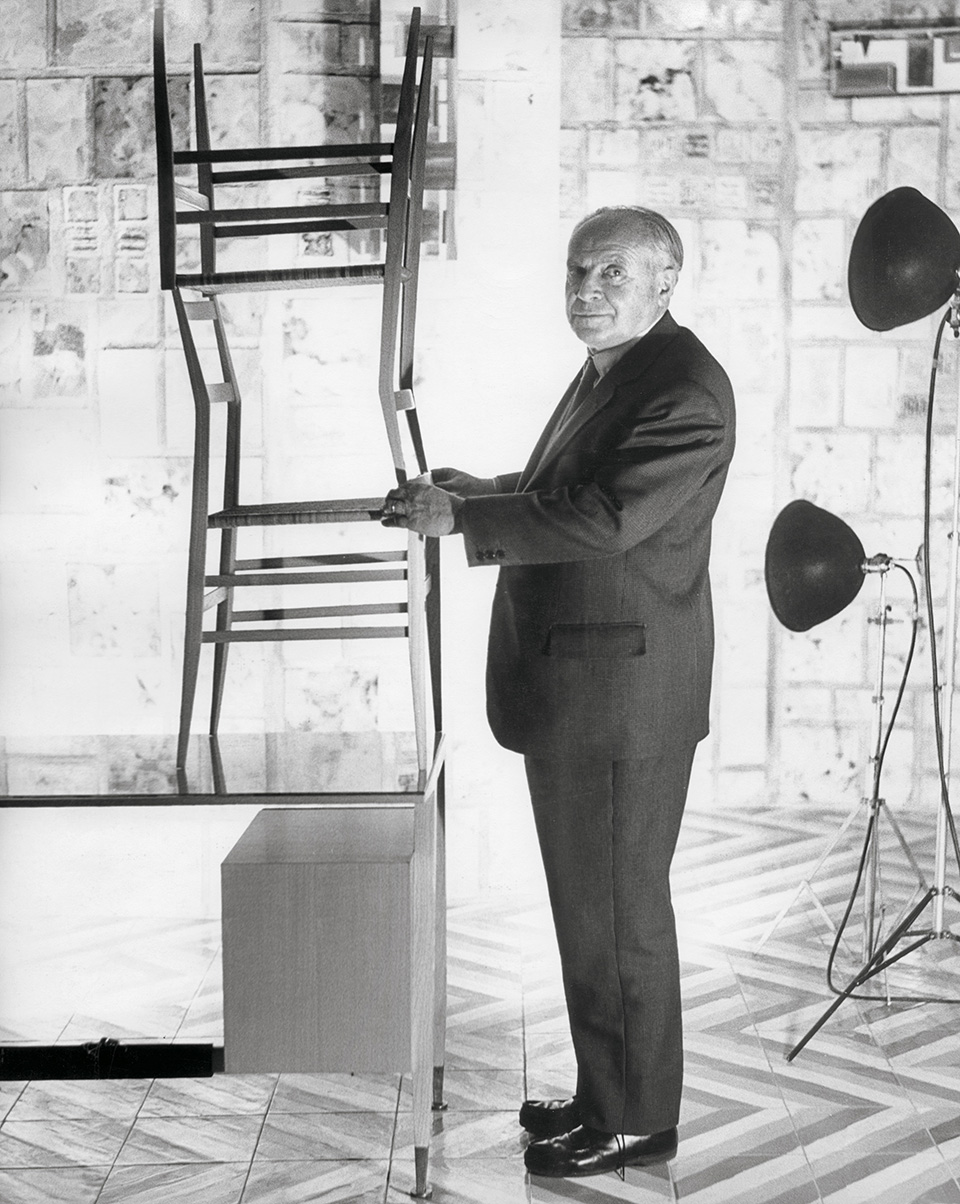

He is best known for his imposing buildings (his Pirelli Tower looms over Milan); his sometimes practical, sometimes impractical furniture (including, in the former category, the lightweight Superleggera chair, produced by Cassina since 1957; and, in the latter, the half-seat-less Gabriela lounge chair of 1971, “for crossing legs comfortably,” Ponti explained); and his achievements as an editor/entrepreneur (he founded Domus in 1928 and ran it until his death with just one break, to launch another publication).

He was also a successful product designer, curator, painter, graphic designer, teacher, author and promoter of Italian industry through his collaborations over 60 years with seemingly every important manufacturer, artist and designer in that country.

A new book from TASCHEN, more than a decade in the making, lays out his achievements in each of those fields. Gio Ponti presents 136 projects, with text by Stefano Casciani, the Italian writer and designer who conceived the book, as well as Ponti’s late daughter Lisa Licitra Ponti and grandson Salvatore Licitra.

Brian Kish, a New York–based architecture and design historian, wrote nearly 1,000 captions for the volume. “Ponti launched Italy into the twentieth century, and this book makes him relevant for the twenty-first,” says Kish, who believes Ponti’s expropriation of historical motifs has a contemporary feel.

The book is full of revelations. But for those who know Ponti for his architecture and his furniture, the real surprise is the ways they came together in rooms that display his seemingly endless supply of creativity. There are many lessons to be drawn from the book, including this one: Ponti was a superb interior designer. Here are just a few of the spaces that prove it.

Palazzo del Bo, 1936–41

From 1936 to 1941 Ponti redid the interiors of the 15th-century palazzo housing the rectorate of the University of Padua. The main staircase, which he called the Scala del Sapere (stair of knowledge), was fitted with multicolored marble risers, a motif he would repeat in other projects. A pair of Ponti-designed sconces made by Fontana Arte —where as a young man he had been named artistic director — illuminate the frescoed wall wrapping around the stairway. Ponti executed the fresco with the assistance of his daughter Lisa and the painter Fulvio Pendini, treating the wall as a void against which the painted figures seem to float.

The rector’s office was outfitted with custom pieces designed by Ponti and made by Luigi Scremin. The bronze door handles are by the sculptor Marcello Mascherini. On the far wall is an enameled painting on copper of one of the university’s founders, rendered by Ponti. Who else could have created a room so serious and so original at the same time?

Andrea Doria, 1949–53

One of Ponti’s most successful collaborations was with the artist Piero Fornasetti, and one of their greatest achievements was the ocean liner Andrea Doria, a symbol of Italy’s postwar renaissance. (Launched in 1953, it was the largest, fastest and supposedly safest of Italy’s new ships.)

In an instance of what Kish calls “exuberance tethered to surrealism,” Ponti engulfed the first-class Zodiac suite in Fornasetti’s lithographic transfer prints in such profusion that they create a deliberate disorientation. The white-on-blue and blue-on-white fabrics are an example of a positive-negative tack that Ponti often took to keep things interesting. He “furnished the walls,” Kish says, with various built-ins, and whenever possible, he hid light sources, allowing Fornasetti’s work to dominate.

The Madonna and Child over the bed was most likely hung by the owners of the ship when it was blessed before its maiden voyage. The religious icons didn’t save Andrea Doria. It sank in 1956 after colliding with a Swedish ship off the coast of Nantucket.

Conte Grande, 1949–53

In the late 1940s, Ponti refurbished several ocean liners that had been used, and badly damaged, in the war. He covered the walls of the Conte Grande’s first-class reading room, a library-like space, in mottled parchment that evokes burled wood. The ceiling is plaster, but with inset strips of anodized aluminum, which Ponti used throughout the ship, elevating an industrial material to a thing of beauty. Concealed lights turn the low ceiling into an overhead display.

Intarsia (wood mosaic) panels depict stylized buildings. Flowers and butterflies adorn an enamel-on-glass panel by Nino Zoncada. With rooms like this, Ponti proved that there was no technique and no material he couldn’t find a place for in interior design.

Ceccato Apartment, 1950

The sheets of Ferrara root wood (known to Americans as burled walnut) that Ponti chose for the reception area of this 1950 Milan apartment have such extravagant, Rorschach-test–like veining as to be almost surreal. But using the same wood on horizontal and vertical surfaces is even more disorienting.

It doesn’t help that the curved living room is on a raised platform, or that the marble floor is set on the diagonal. (Diagonally patterned floors, meant to make rooms more dynamic, were a Ponti signature.) Two recessed shelves, illuminated from behind, display ceramics by Fausto Melotti. The Ceccatos were chocolatiers whose Milan retail store was also designed by Ponti, in the same year, 1950.

Vembi-Burroughs Offices, 1950

In May 1952, Domus featured on its cover the reception area of the Vembi-Burroughs company, a Genoa-based maker of calculators and adding machines. In redoing the company’s offices, Ponti used his own rubber flooring, called Fantastico P, which he developed with the tire company Pirelli. The system he invented allowed colors to be spread over large expanses without repeating patterns, perhaps emulating the striations of marble. (Fittingly, he later used the material in his Pirelli Tower.)

Ponti also designed elegant but functional office furniture and enlisted his frequent collaborator Piero Fornasetti to produce upholstery fabrics that depicted the company’s products. Even serious workspaces can be joyful, or, as Ponti himself put it, “a degree of amusement shouldn’t be excluded.”

Villa Planchart, 1953–57

One of Ponti’s most successful projects outside Italy is the Villa Planchart, in Caracas, Venezuela, completed in 1957. (Kish notes that Ponti ultimately built in more countries than the seminal modernist Le Corbusier.) He designed the villa for Anala and Armando Planchart, art collectors who had made a fortune representing General Motors in South America and who chose him because, Anala wrote, ”we liked everything that appeared in Domus.”

Its rooms were to be filled with tropical plants and other exotica, including Ponti’s own furniture. His leather-upholstered Mariposa armchairs, from Cassina, made one of their first appearances in the front of the main reception area. In the back of that room, geometric sofas and chairs from Ponti’s Diamond line are harlequined in yellow and white. The color-block ceiling is a subtle echo of the marble floor.

Upstairs bedrooms have tiny balconies overlooking the reception hall; the railing around one depicts a sliver of a moon, in bronze. Ponti would have thought through the view from that balcony. Says Kish, “He drew little figures on his plans with dotted lines to show the clients what they were in store for.”

Ponti varied ceiling heights to symbolize the relative importance of various rooms. The double-height dining room contains half a dozen tables of various sizes; their painted tops echo the fragmented marble floor slabs and the painted ceiling. Ponti designed nearly everything in the room, including the surreally long brass sconces. “They would have been glowing and sending light up to the ceiling,” Kish says.

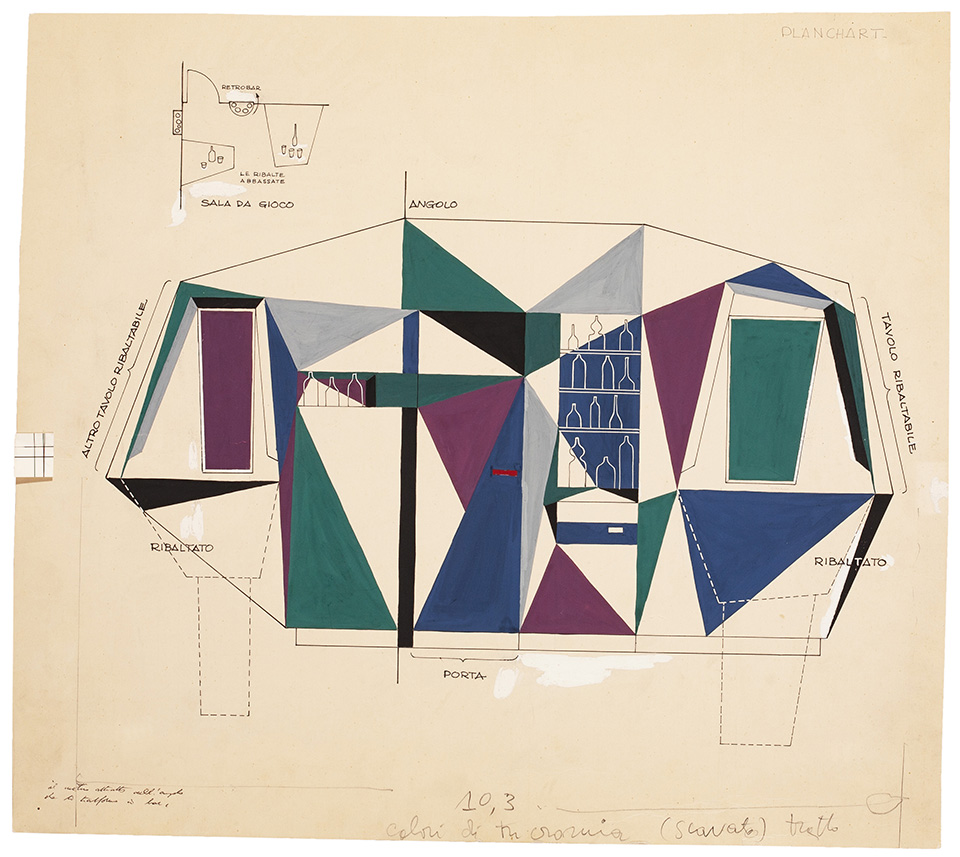

Nothing was left to chance; an ink drawing with colored gouache lays out what looks like a mural of overlapping triangles and trapezoids. In fact, it is Ponti’s rendering of the bar area, where two panels conceal foldout tables and a third a carousel of glass shelves for barware.

Ponti disliked the trophies from the African hunting expeditions of his patron Armando Planchart. Asked to display two antelopes’ heads in the study (pictured at top), he mounted them within a wall of walnut cabinetry, on panels that could be turned 180 degrees, hiding them completely. Below the antelopes are cabinets painted in a fragmented diamond pattern. Ponti’s oddly industrial Round chair (model 852), made by Cassina, is used here for the first time in a domestic setting. The accompanying Mariposa armchairs are also from Cassina.

Villa Arreaza, 1954–56

While working on the Villa Planchart, Ponti designed a smaller house for the Arreaza family, known as La Diamantina for its predominant motif. The main reception room was a festival of blue and white, from tiled floor to painted ceiling. The drapery fabric is Ponti’s Diamanti for JSA. Doors that open to the dining room are disguised as a diamond-patterned mural (broken up by a dark rectangle). The owners’ older furniture was refreshed with new Ponti-designed upholstery fabrics.

Hotel Parco dei Principi, Rome and Sorrento, 1960–64

One of Ponti’s favorite shapes was the elongated hexagon, which appears in everything from small tabletop items to the footprint of his Pirelli building. Here, it’s the shape of the windows in the lobby of the 1964 Rome hotel, as well as that of the sconces, designed by Ponti with Emanuele Ponzio.

Ponti created the interiors using several trademark techniques, including the patterning of all-white surfaces (see the subtly striped ceiling in the far room). Some walls are covered in grasscloth and some in Venetian stucco; others are studded with ceramic pebbles arranged in patterns derived from antiquity. In another example of his inventive use of materials, baseboards throughout the hotel’s ground floor are brass. The Rome lobby is furnished with Ponti-designed sofas and chairs from Cassina (model 899).

In the sister hotel in Sorrento, Ponti used ceramic pebbles to particularly dramatic effect, applying — as he often did — a graphic design approach to interior design. But here the floors are tile, and Ponti used not just his own furniture but pieces by Gianfranco Frattini (the bar stools), Ico & Luisa Parisi and Carlo de Carli, all made by Cassina.

Buy This Book