March 22, 2020Harvey Probber was once one of the most prominent names in the American furniture industry. His sophisticated designs, sold through more than a dozen showrooms in major design centers across the country, found a ready market with interior designers and their affluent clientele. Yet his name has largely faded from popular consciousness. A new exhibition, which I curated at the New York School of Interior Design, aims to remedy that. “Making Connections: Harvey Probber Furniture, 1945–1985” draws on previously unexplored material from the Harvey Probber Family Archive to showcase the wide-ranging activities and accomplishments of a man whose contributions to the design field have never been fully appreciated. Although the exhibition is temporarily closed because of the coronavirus, it will reopen when the school does, hopefully soon.

Harvey Probber, pictured

The exhibition includes some two dozen examples of Probber furniture — ranging from scrupulously restored vintage pieces to contemporary reproductions on which visitors are encouraged to sit — along with dozens of original drawings, color renderings, photographs and press clippings that tell the intriguing story of a man with many interests and prodigious natural talent.

Probber furniture looked expensive, and it was. A 1960s advertisement shows a moving man holding up a Probber dining chair and saying to his companion, “$2,100? This lady is nuts!” Image courtesy of M2L

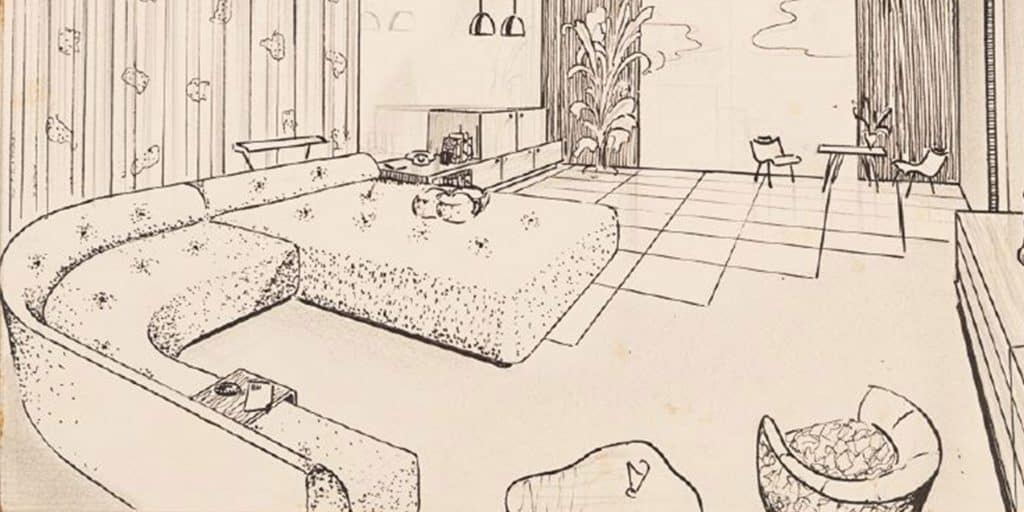

Although Probber’s reputation was based primarily on his refined residential furniture designs, his most groundbreaking achievement was his ingenious use of modularity, creating individual components that could be arranged (and rearranged) in different configurations — an idea so seemingly simple and so universally applied today that its origins have been forgotten. He referred to his invention as a “modular system,” a term not then in general use. For Probber, the way to achieve flexibility in seating was to make upholstered sections in the form of wedges, quadrants, half-circles and shapes he referred to as “bits and pieces of plane geometry … [which] were meaningless alone, but when fused to conventional shapes, profoundly altered their character.”

Always thinking ahead of the competition — and of marketplace needs — he kept up with international design developments as well as the rapidly changing art world. He gave valuable exposure in his showrooms to young practitioners, such as Adolph Gottlieb, of what was then called radical modern art. He introduced the designs of now-celebrated Europeans like Maria Pergay and Angelo Mangiarotti to the American market. In 1948, he opened one of the first showrooms catering exclusively to interior designers. And he was quick to recognize the potential of the contract market, establishing a division to produce executive office furniture well before most of his competitors.

The 1972 Cubo modular seating collection comprised steel-reinforced foam squares and quadrants that could be arranged in different configurations and mounted on either legs or bases. Photo courtesy of M2L

Perhaps the most striking images in the show are the vintage photographs of Probber creations, from the curvy, fringe-trimmed 1940s sofas to the elegant pieces of his most accomplished years, the 1950s and ’60s, when his designs for modular and sectional seating, occasional tables, case goods and dining furniture were among the most admired in the industry. In the 1970s, he moved away from residential design to focus on the burgeoning contract market, while continuing to produce variations on the modular seating he had originated — and which was, by then, being widely copied by others. The exhibition also includes a section on furniture production that contains photographs of hand fabrication in the Probber factory and a sampling of adulatory press clippings — just a few of the hundreds of articles from newspapers across the country that lauded the designer and his work.

Probber was born in Brooklyn in 1922, and apart from some evening classes at Parsons, he was never professionally trained for the career he followed. Combining natural drawing skills with an interest in furniture, he sketched in his spare time and sold his first sofa design for $10 to a small manufacturer when he was just 16 years old. His first real job, two years later, was with a small upholstery firm, where he learned the nuts and bolts of furniture construction, knowledge that would serve him well when he established his own company. His role with the firm also enabled him to design and make seating in which comfort was essential, although aesthetics were always critical. As he told an interviewer in 1958, “No amount of structural ingenuity can compensate for the loss of loveliness.”

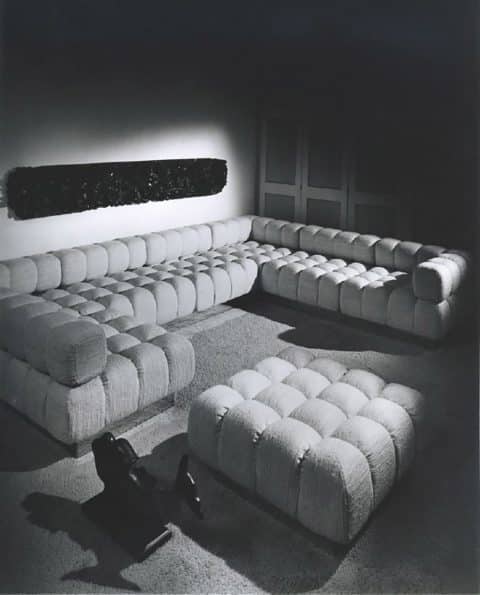

Probber’s 1972 Deep Tuft modular seating collection used urethane foam to create exaggerated tufted seating like that often found in luxury cars. Photo courtesy of M2L

After serving in the Coast Guard during World War II, Probber formed a furniture company with two partners in 1944, but soon decided that the best way to protect the integrity and quality of his designs was to produce them by himself. So the next year, at the age of 24, he established Harvey Probber Inc., first in New York and then as a start-to-finish production facility in Fall River, Massachusetts, that employed specialist craftsmen in wood laminating, metal finishing and upholstery. He later installed a facility for producing cold-cure urethane foam, a new upholstery filling that Probber was the first to bring to the U.S. and that subsequently came into wide use.

While continuing to design furniture and build his manufacturing business, Probber was pursuing a parallel career as a cabaret singer, performing at supper clubs and cafés around the country. Although a 1948 newspaper article described him as “more widely known as an entertainer” than as a furniture designer, the pencil trumped the piano, and he left show business, deciding that the furniture business demanded his full attention and offered the promise of long-term success.

Another variation on the Cubo modular seating collection. Photo courtesy of M2L

Probber considered himself a modern designer, but his brand of modernity favored exotic woods, highly polished lacquer, hand-rubbed finishes and opulent upholstery fabrics — elements largely abandoned by strict modernists like Charles Eames and George Nelson. His designs were sought after by consumers who wanted furniture that was modern but elegant. It looked expensive, and it was. In fact, one of the company’s 1960s advertisements showed a moving man holding up a Probber dining chair and saying to another, “$2,100? This lady is nuts!”

Probber’s Nuclear Sert sofa. Image courtesy of M2L

Probber’s trademark was not any specific design so much as a general look of sophistication. That is, perhaps, the main reason he fell from public awareness after he sold the factory in 1986 (though retaining the rights to his name and his designs). With no successor firm, Probber furniture, for years, was seen only by those fortunate enough to own it already. Recently, however, interior designers like Amy Lau and Shawn Henderson and discerning clients like Julianne Moore are seeking out original Probber pieces from dealers and auction houses. A select group of licensed reeditions is also sparking a new wave of interest in designs that look as good today as they did more than a half-century ago. Probber leaves a legacy of collectible and eminently usable pieces, and a reputation that deserves its current revival.