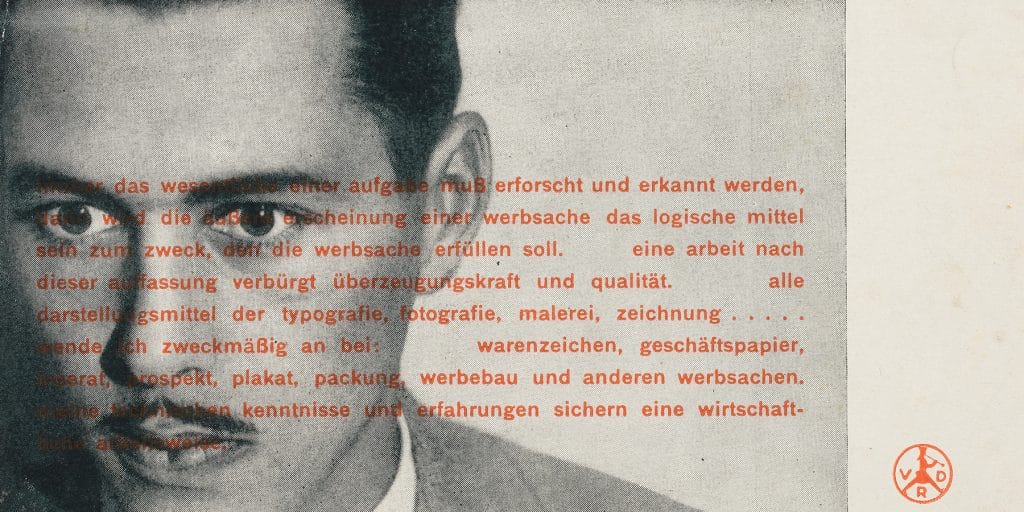

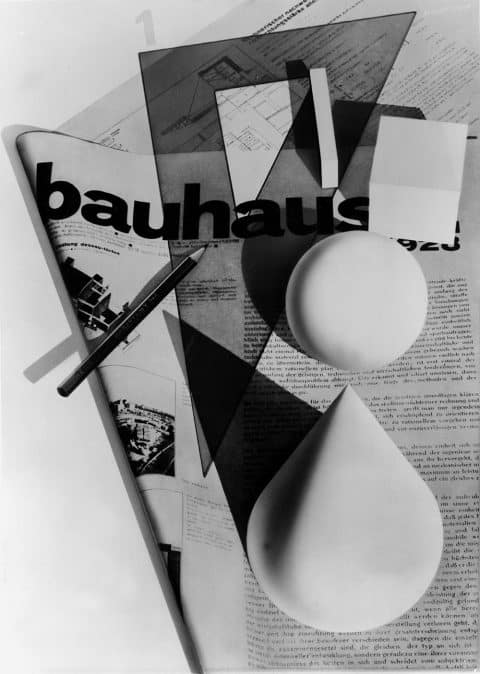

January 26, 2020Bauhaus artist and designer Herbert Bayer is the subject of a show currently at New York’s Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. Included in the exhibition is the photomontage cover (above) that he created in 1928 for the first issue of Bauhaus magazine (INTERFOTO/Alamy Stock Photo). Top: A business card Bayer created for himself in 1928. All photos by Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution; all artwork © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, unless otherwise noted

Among the many inspiring exhibitions celebrating the 2019 centenary of the founding of the Bauhaus, “Herbert Bayer: Bauhaus Master” stands out. The Austrian-born Bayer (1900–85) is widely acknowledged as one of the most influential graphic artists of his time, but this show — on view through April 5 at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, on New York’s Upper East Side — demonstrates the full spectrum of his extensive achievements. The artistic polymath made his mark as a photographer and master of photomontage, a typography creator, magazine art director, advertising guru, architect and more.

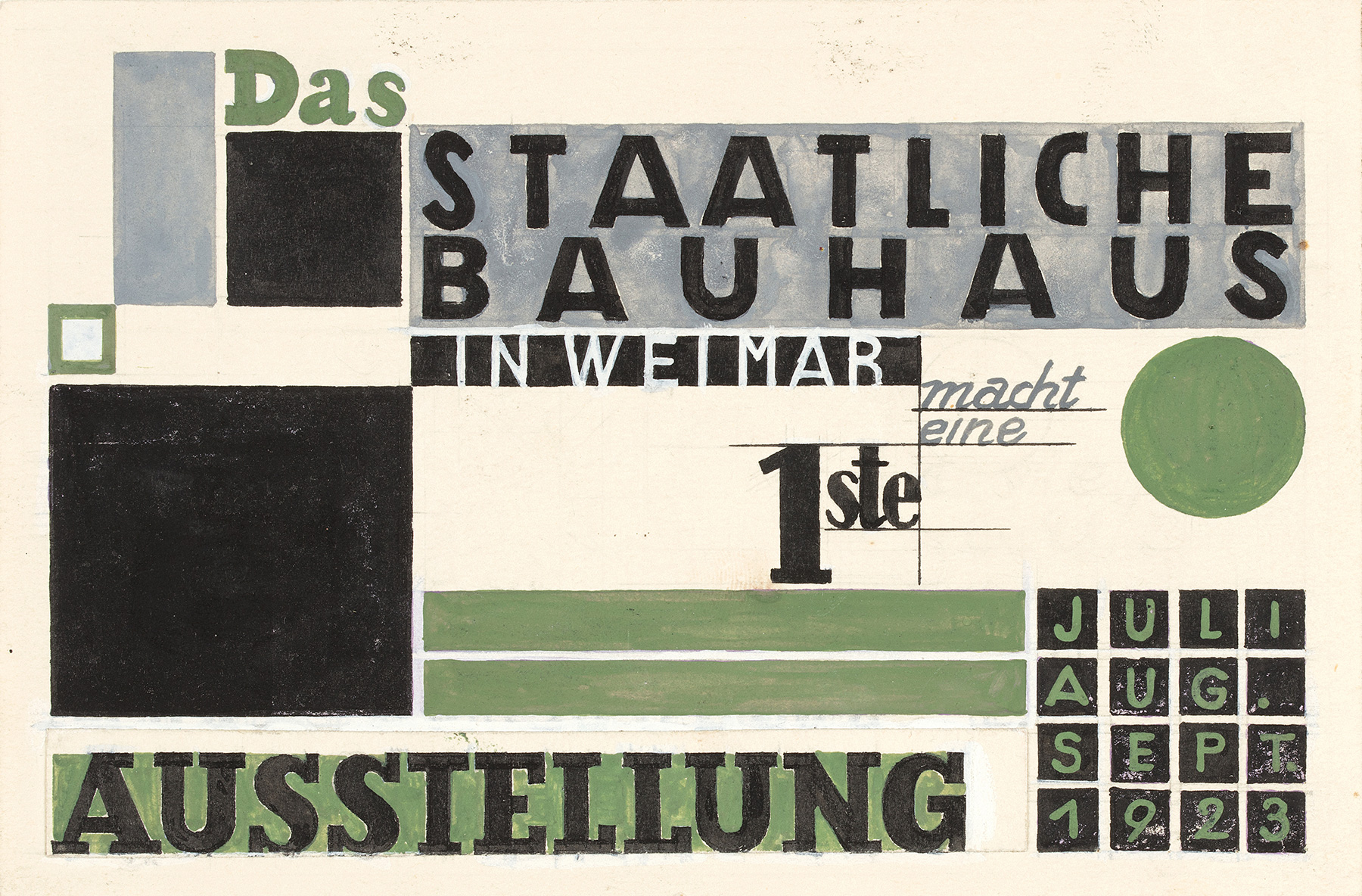

The exhibition opens with the stunning posters, book covers, stationery and postcards Bayer designed in the very early 1920s as a student at the Bauhaus, the revolutionary German art and design school in Weimar that sought to integrate art and design into daily life. He studied under Russian-born Wassily Kandinsky, who became his mentor, and was greatly influenced by Kandinsky’s book Concerning the Spiritual in Art, heartily embracing its premise that the arts can and should serve society.

The Cooper Hewitt show contains diverse works from across Bayer’s career, beginning with those he created in the early 1920s while at the Bauhaus and continuing through his tenure as a teacher at the school and then his time as a working artist, designer and creative director in Berlin and the U.S.

Bayer left the Bauhaus in 1923 to tour Italy with a friend, then rejoined two years later, hired to teach advertising, design and typography at the school’s new home, in Dessau. There, he designed catalogues, featuring photography and machine-based printing, that promoted Bauhaus-made “goods for the home,” including handmade furniture, wallpaper and housewares. And he created a new “universal” alphabet: a streamlined sans serif restricted to lower-case letters that became the Bauhaus’s signature font.

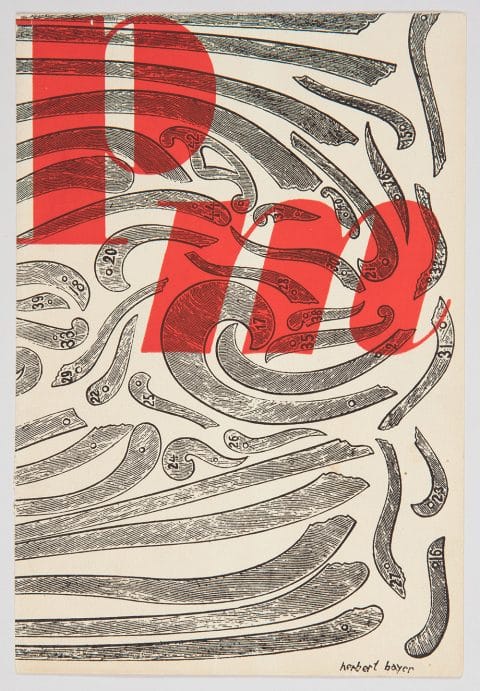

Bayer created this cover for the German magazine PM in 1938, shortly before he left Berlin for New York.

Bayer followed the Bauhaus dictum that no art form is better than any other by practicing them all. The show displays his cover for the initial, 1928, issue of Bauhaus magazine, for which he cut and pasted photos and print. Bayer first photographed a cube, cone, sphere and pencil under a strong, raking light, creating dramatic shadows. He then merged that picture with a second one of a triangular drafting tool, called a set square, and a folded page from the magazine itself. The result is a stunning example of his imaginative photo montages.

The show then moves to the decade, beginning in 1928, that Bayer spent in Berlin after he stopped teaching at the Bauhaus. (He quit along with founder Walter Gropius and fellow teachers Marcel Breuer and László Maholy-Nagy when the school’s finances grew strained.) Bayer became the art director of German Vogue, moving on, when the magazine closed during the Depression, to the ad agency Dorland International, where he created the advertisements for clothing, textiles, toothpaste and nose drops on view. He also did magazine covers and outdoor billboards and masterminded the design of several important international exhibitions, including the German section of the 1930 Exposition de la Société des artistes décorateurs in Paris.

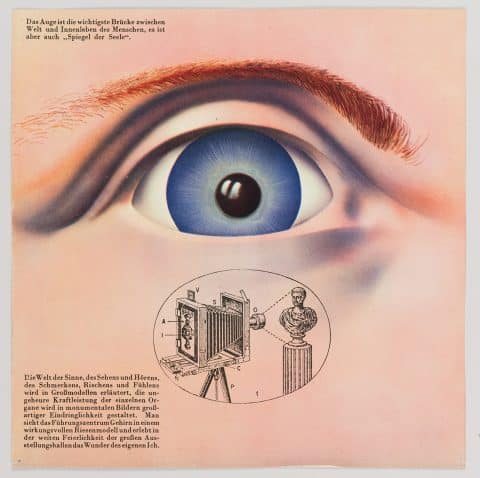

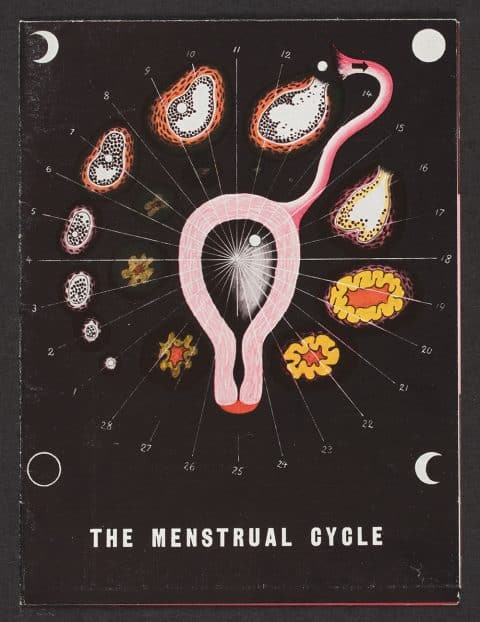

Bayer conceived this illustration for the 1935 booklet Das Wunder des Lebens (The Miracle of Life).

Although the show is largely celebratory, it doesn’t avoid the work Bayer did for the Third Reich, beginning in 1933, when Adolf Hitler was elected chancellor. One brochure for the Berlin Trade Fair and Tourism Association, presumably ordered to coincide with the Olympics that year, has on its cover an orange globe with an oversized Germany, in bright green, in the center.

By 1938, Bayer had become dismayed by the political situation in Germany, and at the invitation of Walter Gropius — who was then chair of the architecture department at Harvard, having fled the Nazi regime in 1934 — he left for the U.S. Gropius had been asked to curate an exhibition on the Bauhaus for the Museum of Modern Art, but he didn’t have time and so asked Bayer to help. Bayer ultimately did it all, including gathering material in Germany, creating the exhibition plan and overseeing the catalogue. The show traveled throughout the U.S., and Bayer’s stateside career took off.

Bayer created design for this Bauhaus postcard in 1923, during his final months as a student at the school.

In the early 1940s, he served as chief art director at Wanamaker’s and worked in advertising and package design at J. Walter Thompson. The exhibition contains his ad for Noreen hair dye adorned with red, yellow and blue swirls, a sharp nod to the work of Robert and Sonia Delaunay, as well as a poster, for the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, showing a glowing test tube with the text “Polio Research: A Light Is Beginning to Dawn.” Another poster, for an Olivetti adding machine, is perhaps the best example of his inventive integration of typography and graphics. The design resembles a long piece of tape unfurling like a ribbon, printed with digits in brightly colored boxes and overlaid on a gray-and-white grid dotted with arithmetic symbols.

Bayer designed this brochure in 1939, for a pharmaceutical company selling drugs to alleviate cramps.

In 1945, Bayer began a long stint working full-time at the Container Corporation of America (CCA), and the show includes some of the clever ads he did there — surprisingly conceptual pieces for a company that was essentially making cardboard boxes. He created CCA’s long-running series “Great Ideas of Western Man,” which aimed to enlighten the public through inspiring quotes. One poster features Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 take on responsibility: “I hold that while man exists, it is his duty to improve not only his own position but to assist in ameliorating mankind.” At the bottom is a tiny drawing of a cardboard box and the company initials.

The exhibition also showcases some newly uncovered Bayer materials, many from a cache of 500 works acquired by the museum in 2015. Among them is a page from a 1935 booklet that Bayer designed, titled Das Wunder des Lebens (The Miracle of Life). On it is a painting of an eye with a sketch of a camera, to show how the retina records images. Bayer was fascinated by the workings of the eye and incorporated pictures of it into his commercial and editorial work.

Bayer designed not only this poster for the German section of the Exposition de la Société des Artistes Décorateurs in Paris, but also much of the country’s display at the Grand Palais.

Sadly, the Cooper Hewitt show does not contain Bayer’s paintings, although he famously called painting “the continuous link connecting all the facets of my work.” Nor does it have the sculptures, wall murals, furniture, earth art and buildings he designed for the Aspen Institute between 1946 and 1975. These will be displayed in the recently announced Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies, in Aspen, founded with a $10 million donation from Lynda and Stewart Resnick, Bayer collectors and owners of the Wonderful Company.

Although not comprehensive, the Cooper-Hewitt show unequivocally demonstrates how one man, and one school, changed the evolution of contemporary graphics in America over a 40-year period. It illustrates, as Daniel Libeskind wrote in the foreword to Gwen Chanzit’s 2005 book, From Bauhaus to Aspen: Herbert Bayer and Modernist Design in America, that Bayer did “to 2-D graphic and design work what Mies van der Rohe did to architecture.”