April 10, 2017This gold, platinum, ebonite, citrine, diamond and enamel Mystery Clock with Single Axle, ca. 1921, was produced by Cartier and is included in “The Jazz Age,” the current blockbuster show at the Cooper Hewitt (photo by Marian Gerard, Cartier Collection). Top: Muse with Violin screen (detail), 1930, by Paul Fehér is another exhibition highlight (photo by Howard Agriesti, courtesy of Rose Iron Works Collections, LLC).

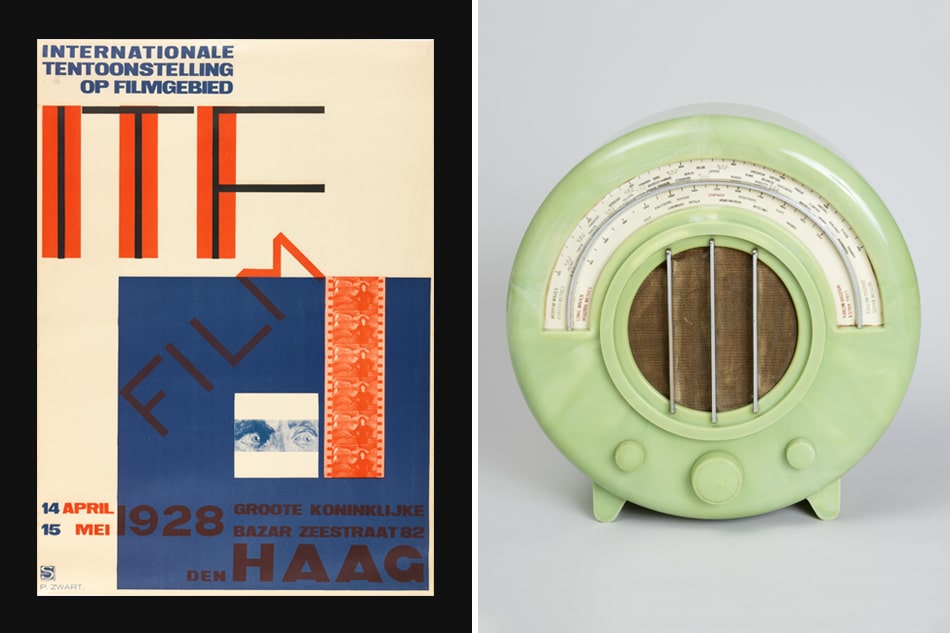

The Twenties weren’t called Roaring for nothing. That is made even more apparent by “The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s,” the ambitious exhibition that just opened at Manhattan’s Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. The wide-ranging show aims to capture the tastes of the nation in the heady, optimistic era between the end of World War I and the crash of 1929. “That’s when you have the first radio broadcasts and film talkies, and women starting to do things outside the house,” says Sarah Coffin, the Cooper Hewitt’s curator and head of product design and decorative arts. “After not having traveled during the war, Americans were sailing to Paris again, seeing Cubism and hearing jazz.” Coffin, who organized the show with Stephen Harrison, curator of decorative art and design at the Cleveland Museum of Art, where the exhibition moves in September, continues: “People were suddenly exposed to a lot of different influences, and it all came together in multiple different strains of design.”

That’s one thing Coffin would like to clarify. “It’s not an Art Deco show,” she says, referring to the immaculately crafted furnishings and objects first showcased at the seminal 1925 Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels moderns in Paris that later lent the style its name. “It’s a much broader-based look at both art and design of the twenties, and how inventive it was.”

This lacquered wood dressing table and bench, ca. 1929, after Léon Jallot, was sold at Lord & Taylor. Photo by Matt Flynn, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

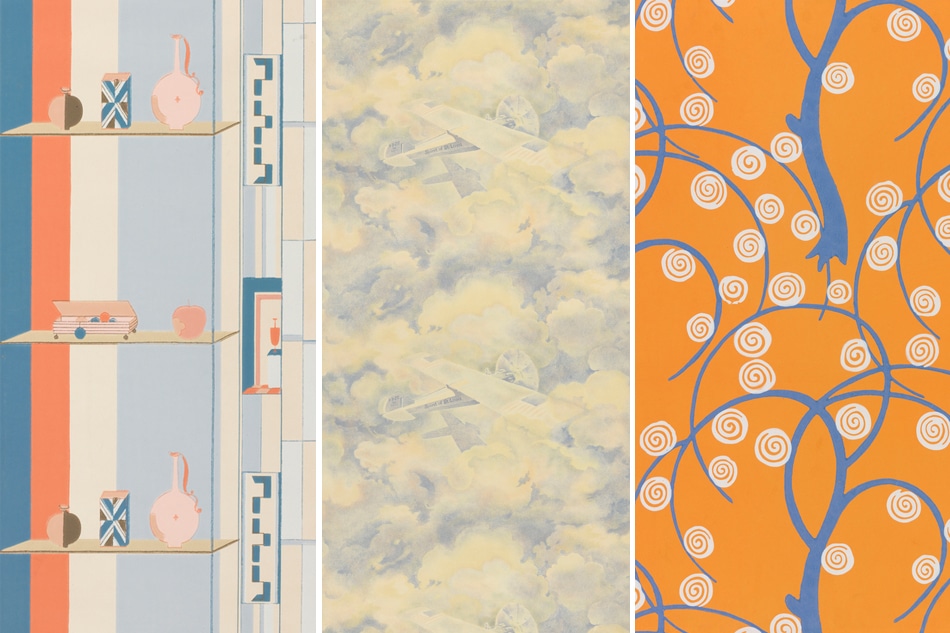

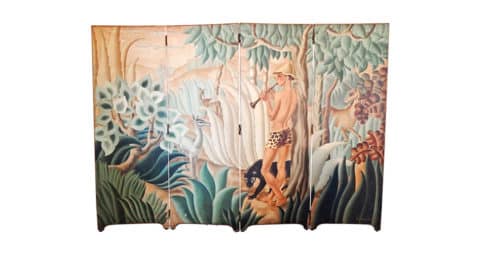

Among the 400 objects in the exhibition, which include furniture, jewelry, fashion, textiles, tableware, wall coverings, paintings and posters, are such icons as Joseph Stella’s oil of the Brooklyn Bridge, with its radiating lines and skyscraper imagery, and the strongly geometric circa 1928 silver-leafed screen by Donald Deskey. Film clips of jazz greats, “lifestyle items” like cocktail shakers and cigarette cases and wallpaper with an aviation motif inspired by Lindbergh’s sensational transatlantic flight of 1927 will also be on display, along with a circa 1928 Skyscraper Bookcase desk by Vienna-born designer Paul Frankl and a mid-1930s daybed of birch plywood and steel tubing by Austro-Hungarian designer Frederick Kiesler, representing the contributions of Bauhaus-inspired designers who came to the U.S. after World War I.

The show’s purview is even broad enough to include some 17th– and 18th-century furniture and silver in a section titled “Persistence of Traditional Good Tastes.” “There was a great love of antiques, Colonial Revival and traditional decor that went on throughout the decade. That’s what the Hewitt sisters were acquiring in the 1920s,” says Coffin, referring to the women who founded a museum that became the basis for the Cooper Hewitt, in 1897. (It’s been housed in Andrew Carnegie’s landmark Fifth Avenue mansion since 1976.)

All that said, a significant number of pieces on display in “Jazz Age” are classic French Art Deco, including several shown at the 1925 Paris expo, some of which were purchased by Americans and brought back to the U.S. A red lacquer metal vase by Jean Dunand has “two of the greatest Art Deco provenances” — shown at the 1925 exposition and again the following year at the Metropolitan Museum of Art — says 1stdibs dealer Stephen Kelly, of Manhattan’s Kelly Gallery, who lent five items to the show. These include a circa 1925 wrought-iron vanity and mirror by Edgar Brandt, a Cubist-inspired clock by Jean Goulden in champlevé enamel and a pair of stoneware Sèvres vases purchased at the Paris exhibition by John D. Rockefeller and his wife for their Park Avenue apartment.

This wallpaper print, named Modernistic, was designed by Charles Burchfield in 1927 and manufactured by M.H. Birge & Sons Co.

The curators of “Jazz Age” combed private collections to find items not often seen by the public. “We tried to go for important works not on everybody’s radar,” Coffin says. One showstopper that’s been exhibited just once before is an extraordinary pair of lacquerwork doors depicting angels standing on skyscrapers, designed by Séraphin Soudbinine and executed in mother-of-pearl and gold leaf by Jean Dunand. Solomon and Irene Guggenheim commissioned them for their Port Washington music room after seeing Dunand and Soudbinine’s work in Paris in 1925. “These doors represent the Guggenheims’ first foray into modern art,” Coffin says. Shortly thereafter, they began collecting for what was to become the Guggenheim Museum.

Americans who stayed home in the 1920s were nevertheless exposed to the modern style showcased at the Paris expo by way of spin-off exhibitions that traveled to eight U.S. museums and catalogued displays in department stores. Homegrown versions, like the silver-leafed circa 1929 Paul Frankl bookcase currently available from Dallas’s Machine Icon, can be found on multiple 1stdibs storefronts.

Some department stores, including Macy’s, Lord & Taylor and W. & J. Sloane, produced their own Paris-inspired furnishings. Among the items in the Cooper Hewitt show is a circa 1929 red lacquered vanity and bench based on a Jallot design made and sold by Lord & Taylor. U.S. furniture manufacturers attending the 1925 Paris expo “made sketches of designs to incorporate into their mass-produced furniture lines,” says Gary Calderwood, of Calderwood Gallery. “The French were not happy about that.” But it did make the style more affordable and had an incalculable effect on the taste of the American public going forward.

Jean-Michel Frank designed this 1930 wood and leather club chair.

The 20th century meets the 21st in the Immersion Room at the Cooper Hewitt, where visitors are able to project 1920s samples from the museum’s wallpaper collection, the largest in the country, onto a wall to see how they would have looked room size. Many of the projectable designs are strikingly modernistic or geometric, like the stylized trees in orange and blue of the circa 1920 paper distributed by Nancy McClelland, an early luminary in the interior design profession.

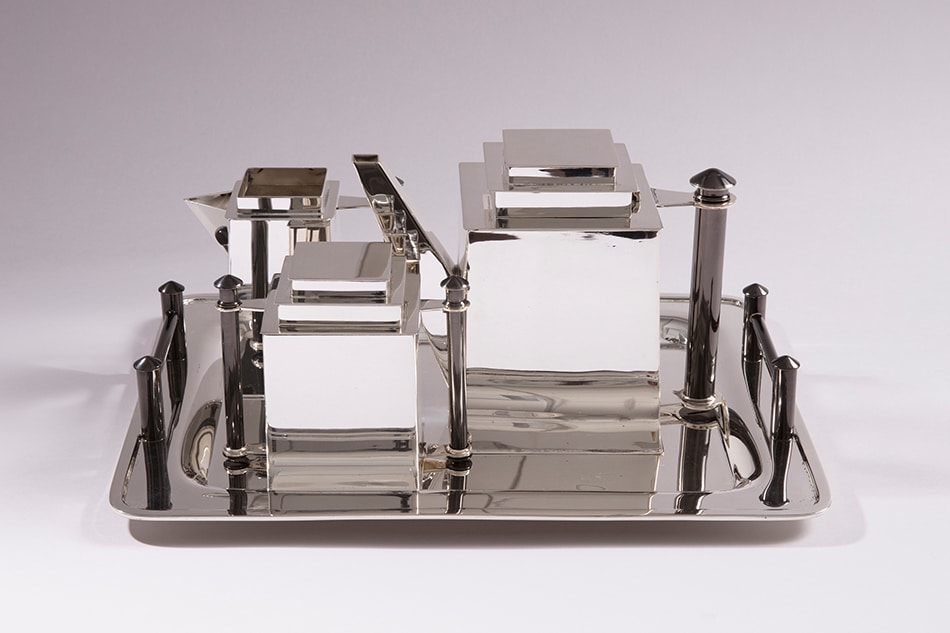

If the home furnishings featured in “Jazz Age” are any indication, the 1920s ban on production and distribution of alcohol, known as Prohibition, seemed to do little to stop its consumption. “You were allowed to consume in your own home,” says Nicole Kapit, president of sales and acquisitions for New York–based Newel. “With the introduction of the radio, people were holding private parties that almost paralleled a nightclub scene, with bar cabinets and big bergère chairs.” Kapit’s point is borne out by the 1930 leather club chair by Jean-Michel Frank and a gleaming silver-plated cocktail set manufactured by New York’s E. and J. Bass Company around 1928, both in the show. The revelers “didn’t know what was ahead of them,” Kapit says.

After the stock market crash of October 1929, the glamorous, fancy-free life documented in the Cooper Hewitt exhibition wound down, and the Twenties ceased to roar.