December 12, 2016The new show “Pierre Chareau: Modern Architecture and Design,” at New York City’s Jewish Museum through March 26, pays tribute to the French furniture designer, whose work is hard to find in the U.S. (portrait by Laure Albin-Guillot). Top: Chareau’s most famous creation may well be Paris’s Maison de Verre, 1932. Photo © Mark Lyon

To say that Pierre Chareau’s work is hard to come by is an understatement. In the United States, there is a single example of the French architect’s work on public view — an armchair at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The museum has a second chair in storage, and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York has a stool. Chareau’s creations only occasionally turn up at auction, and there has never been a dedicated exhibition of his work in North America.

The dearth of examples of Chareau’s output is surprising, considering that he spent the last decade of his life, from 1940 to 1950, in New York after fleeing Nazi-occupied France. During that decade, he designed two houses. Unfortunately, one, created for the artist Robert Motherwell in East Hampton, New York, was demolished in 1985, and the other, in Upstate New York, has been changed beyond recognition.

In the new exhibition “Pierre Chareau: Modern Architecture and Design,” running through March 26 at the Jewish Museum in New York, the architect is finally getting his due. The show pulls together more than 180 works from public and private collections to offer a comprehensive overview of his oeuvre. “Chareau was very famous in his own day, came to the U.S. in exile in nineteen-forty, and yet never had a show here,” says Esther da Costa Meyer, a professor of the history of modern architecture at Princeton University, who guest-curated the exhibition. “It was especially important for us to honor him. Chareau left traces here, and I was interested in picking up that story.”

La Religieuse floor lamp is made of mahogany and alabaster and vaguely recalls a nun in her habit. Photo by Georges Meguerditchian

Most people familiar with Chareau’s work know it through the Maison de Verre, the house he completed in Paris in 1932 with the Dutch architect Bernard Bijvoet and French metalworker Louis Dalbet for the physician Jean Dalsace and his wife, Annie. The structure is a modernist masterwork of translucent glass-brick facades, exposed steel, a retractable staircase and sliding panels and screens. Still intact, thanks to the stewardship of current owners Robert M. Rubin and Stéphane Samuel, the home presaged shifts in residential architecture that are still playing out today. Even today, it exerts an influence on a wide range of architects, including Tom Kundig of Olson Kundig and Elizabeth Diller of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the firm that designed the Chareau exhibition.

“Chareau is one of my heroes from when I first started in architecture,” says Diller, whose immersive ideas for bringing the exhibition to life include virtual reality goggles for viewing furniture in the interiors for which they were originally designed, as well as a sliding projection screen that presents digitally rendered slices of the Maison de Verre. “Chareau is this really unusual, idiosyncratic figure. He somehow bridged decorative interiors with industrial language and mobility.”

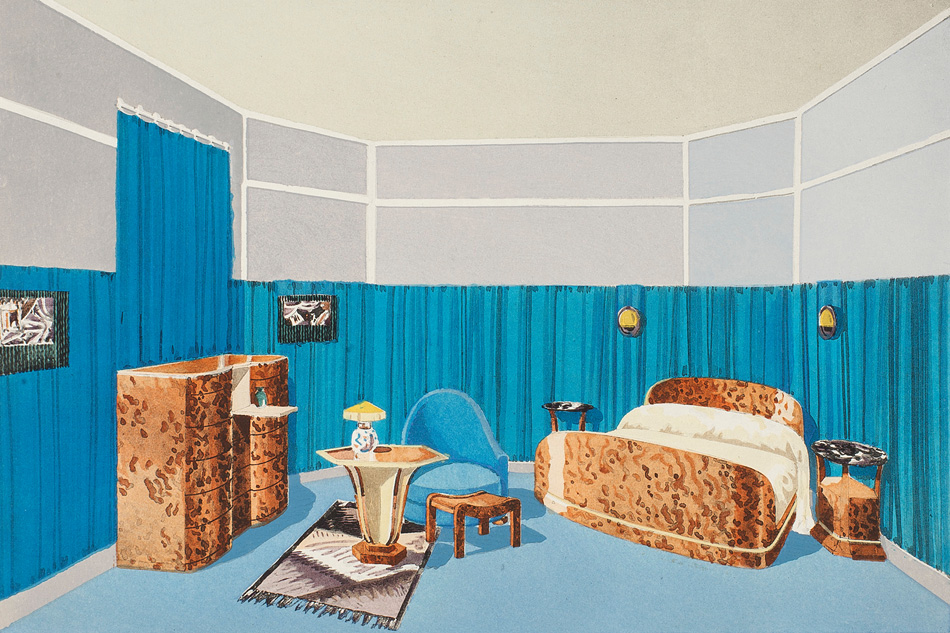

The exhibition makes clear that it would be a mistake to assume that the designer was a metal- and glass-obsessed minimalist who could be lumped together with the Bauhaus. Chareau, best known during his lifetime as an interior and furniture designer, started out in 1899 creating furniture for ocean liners and hotels before establishing his own studio in 1919. He soon joined the Société des artistes décorateurs and began producing custom furniture and light fixtures for wealthy clients using luxurious materials like exotic woods, silver, bronze and alabaster. The exhibition includes several of these creations, a sumptuous rosewood daybed and a side table whose shapes evoke tulips. But in Chareau’s hands, many pieces took on innovative traits. “He mixed handmade wrought iron with Macassar ebony, ivory and sharkskin,” says da Costa Meyer. “These two parts are held in tension. It shows Chareau paying tribute to modern life, yet hanging on to the great tradition of the French ensemblier.”

“Chareau is this really unusual, idiosyncratic figure,” says architect Elizabeth Diller, who designed the exhibition. “He somehow bridged decorative interiors with industrial language and mobility.”

Chareau’s telephone table has nesting sections that slide out like a fan. It’s topped here by a Religieuse table lamp.

Some of his furniture designs have moving parts that allow them to be transformed. A walnut and wrought-iron bookcase has a connected circular table that swivels into place. A walnut side table comprises nesting sections that slide out like a fan. A painted metal chair collapses with a novel type of folding mechanism. “Chareau made a specialty out of this mobility, piece after piece after piece,” says da Costa Meyer. “He was one of the first, if not the first, to do so.” A few of his designs even have anthropomorphic qualities, she notes, including his La Religieuse (“the nun”) table and floor lamps, which have vaguely tunic-shaped wooden bases topped by triangular shades made of translucent alabaster that are reminiscent of nuns’ cornettes.

Chareau and his wife, Dollie, were passionate about the arts. They owned paintings by Motherwell, Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian, Amedeo Modigliani, Fernand Léger, Max Ernst and others — many of which are presented salon-style on a wall in the museum. While still living in Paris before the war, Chareau displayed these pieces in rooms he designed for exhibitions, as well as in his boutique and his home, where he sometimes also hosted poetry readings and film screenings.

When he moved to New York in 1940, his career largely came to a standstill, even though he still produced drawings for furniture. He eventually began selling some of his art collection. “By the time he reached the U.S., he was isolated. His wife would only arrive two years later, he had no links to the profession or trade, and he couldn’t speak English,” explains da Costa Meyer. “He had to survive.” To make ends meet, he sold key works, including a Modigliani that would later be donated to the Museum of Modern Art, and a Mondrian that would land in the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Of course, he had no way of knowing that many of those pieces would be reunited, as part of the first thorough examination of his work in North America, more than half a century later.

Shop Pierre Chareau on 1stdibs