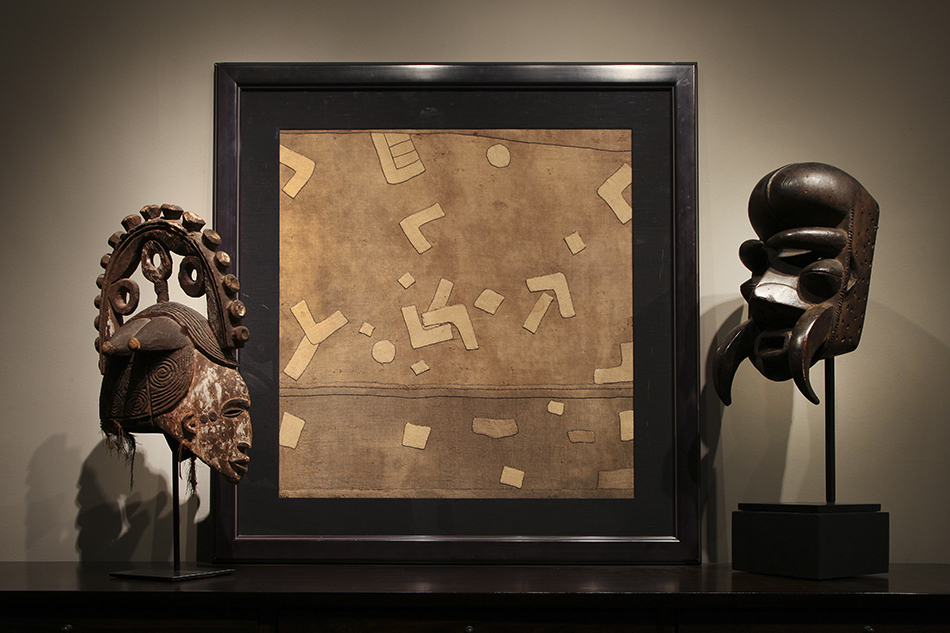

August 3, 2015Dori Roortenberg, co-founder with her husband, Daniel, of Jacaranda Tribal, stands before a set of early-20th-century Rwandan Tutsi screens. Top: One of a pair of extremely rare cattle horns from the 1880s engraved with scenes of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879.

Among the rare and fascinating treasures in stock at Jacaranda Tribal, a by-appointment gallery in Manhattan that focuses on the native art of South Africa, one piece particularly stands out: a set of cattle horns from the 1880s engraved with scenes of the famous Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. Jacaranda’s owners, South African Daniel Rootenberg and his American wife, Dori, explain that the engravings also depict vignettes of British military life.

THE BACKSTORY

Americans who don’t follow British colonial history (or who never saw the thrilling 1964 film Zulu starring Michael Caine) can be forgiven for not knowing about the Anglo-Zulu War in South Africa. After the 1867 discovery of diamonds in what is now South Africa, the British Empire decided to create a federation that would include the independent Kingdom of Zululand and the South African Republic founded by the Dutch Boers. The British wanted to control the entire region, presumably to procure laborers to farm and mine for them. They envisaged a federation like the one they had already successfully established in Canada.

In 1878, without the approval of the British government, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, high commissioner for the British Empire in South Africa, sent a series of outrageous ultimatums to Cetshwayo, the Zulu king, purposely trying to provoke him and instigate a war so the British could take control of Zululand. The commissioner succeeded. When the ultimatums were not met, the British invaded.

Much to the surprise of the British, the Zulus were ferocious, disciplined fighters. The Zulus famously won the bloody opening battle, despite the fact they were fighting with spears against British rifles.

As the Victorian novelist Sir Henry Rider Haggard wrote at the time from Africa: “Wherever [Cetshwayo’s] warriors went, the blood of men, women and children was poured out without stay or stint; indeed he reigned like a visible Death, the presiding genius of a saturnalia of slaughter.”

The engraved narrative is dense with detail, showing British soldiers marching and sprawled dead on the ground, Zulu warriors advancing in formation while Zulu mothers with babies on their backs watch.

A photograph of Cetshwayo from around 1875 depicts an enormous, athletic man sitting on an English stool, naked except for his loincloth. He looks formidable. It took the British five months, three weeks and two days to conquer the Zulus. The British lost 1,726 men; the Zulus more than 6,000.

The narrative depicted on the horns is dense. The uniformed British soldiers, rifles in hand, advance as a man blows a trumpet. They are followed by wagons full of reserve soldiers. The Zulus also advance in formation, carrying spears and cowhide shields. On the side stand the women, large tight buns atop their heads and babies in their arms, watching it all.

There are scenes of fighting, with British soldiers flat on the ground, bayonets out, confronting the approaching Zulus. Some Brits are already dead, strewn on the field. We also see the cavalry, mounted on horses with spindly legs and extra-long necks (looking a bit like giraffes). Here, some Zulus are surrendering, hands in the air, shields on the ground.

RARITY

“These engraved horns are very rare — there are about a dozen known — and it’s rarer still to have a pair of them, especially one with the original shield mounting,” says Daniel. “They are also important because they were not done by a white artist. With them, we get a glimpse of what colonial life looked like to a native South African. This gives them historical importance.”

Dori explains that there are a few similar South African horns in private collections and in museums like the Smithsonian, the British Museum, the Glenbow Museum in Calgary and the KwaZulu-Natal Museum in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

The Rootenbergs have expertise in South African art. “We were collectors before we went into business,” Daniel says. Both Rootenbergs had careers in other fields (he was the CFO of Weight Watchers; she was a fashion designer) before deciding to become full-time dealers. After seeing “African Forms,” a landmark 2001 show at the Museum for African Art (then in Soho), they began collecting South African art. They have also been generous to other institutions, donating pieces (and their expertise) to the 2011 show “Art of Daily Life: Portable Objects from South East Africa” at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Scholars of 19th-century engraved cattle horns believe an artist in the Zulu kingdom — who was not living as a “traditionalist” but was somehow involved in the colonial economy — carved these horns and a handful of others, which are now in private collections and museums, for the European curio market.

The Rootenbergs point out that scholars have carefully examined similar engraved cattle horns. To wit, they cite an article entitled “Visual Narratives of the Anglo-Zulu War,” by Patricia Davison, a research associate at the Iziko South African Museum, in Cape Town. Davison, who has published widely on Zulu art, here studied the known 19th-century engraved cattle horns with battle scenes from Natal, South Africa. “As the imagery on more of these horns was examined, it became clear that with the exception of the single horn in the KwaZulu-Natal Museum, they were all engraved by the same hand,” she writes. “Archival evidence points conclusively to the fact that the artist, whose name is as yet unknown, was living near Newcastle, South Africa, in the early 1880s and was known for his depictions on cattle horns of the battle of Isandlwana and related events [in the Zulu War].”

She continues: “We have no biographical information about the artist but we can infer that he was not living as a traditionalist in the Zulu Kingdom but was incorporated in some way into the colonial economy and engraved horns for the early curio market.” As Davison writes, “He must have been in a position to observe the details of military ceremonial, regimental dress, weaponry, marching bands and recreational events.”

Such engraved horns, Dori says, went included among “native works” that were sent to London for shows like the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition. They represent a genre of art made by Africans for Europeans.

MATERIALS

Dori says the shape of the horns suggests that they derived from Nguni cattle rather than Africander cattle.

She describes how they were made: The horn surface was scraped to create a smooth background. Then a sharp blade or fine point was used to create the engravings. The drawings were then blackened with soot to make them stand out.

Row upon row of marching Zulu warriors parade along the entire length of the topside of each horn.

PROVENANCE

The Rootenbergs bought the horns a few years back from a British gallery that specializes in ethnographic works of art. That gallery had found them at a regional auction house, where they’d been consigned by a family who had inherited the stock of an early-20th-century dealer. “We paid a ridiculous price,” Daniel admits, “but we had to have them.”

Dori explains that they are open to anything very special, “We have branched out to all areas of antique African and Oceanic art to appeal to a broader collecting community in the tribal area.”

CONDITION

There is wear to the mount, but the horns are in near-perfect condition. “We have left the mount exactly as it is,” Daniel says.

PRICE

The Rootenbergs are asking $60,000 for the carved horns. “We know of a single carved horn that recently sold in that range,” Dori says. “It’s much rarer to have a pair.” Adds Daniel, “Our set is so rare you could pretty much ask anything.”

Their timing may be good. Chris Kay, a reporter for Bloomberg, recently published an article on the bull market for contemporary African art. He wrote that the average lot prices at Bonhams auction house have increased about fivefold, to $50,000, since Bonhams started specialized sales of contemporary African art eight years ago in London. He noted that 50 percent of the buyers were Europeans.

Of course, these horns are not contemporary, but, Dori says, “they do speak on many levels — to the artist’s artistic abilities, to anyone who has an interest in history and to anyone who collects documents. And they are still relatively affordable.”