April 13, 2015Judith Henry has spent her career bringing the proverbial “faces in the crowd” into focus, incorporating snippets of overhead conversation or a snapshot of a passerby into her artworks. Top: Two new series, featuring the artist herself, are on view at New York’s BravinLee Programs through May 16.

The artist Judith Henry is fond of making statements like, “I prefer to be invisible” and “I’ve always been a voyeur.” Yet over the years, she’s been steadily leaving her mark on the more Dada-esque reaches of the New York art world.

Henry, who describes herself as “a minimalist and a conceptualist,” has long been fascinated with typefaces and fonts: In the early 1970s, she was making drawings that incorporated pages from Freud’s writings and municipal telephone books, covering them with inked crosshatches that simultaneously highlight and obliterate the words and names. “They look like minimalist stripes,” Henry observes of the phone-book works, “but each one is a real person.”

She has frequently dealt with humankind more overtly, as with such projects as Who I Saw in New York, 1970–2000 — a three-decade archive comprising thousands of surreptitiously snapped photographs of people on the street — and others in which these images are combined with texts drawn from snippets of overheard conversation. She is probably best known for Crumpled Paper Stationery, Fluxus-like novelty writing paper that she created in the late 1970s while supporting her artist husband and their children as a book designer at Alfred A. Knopf.

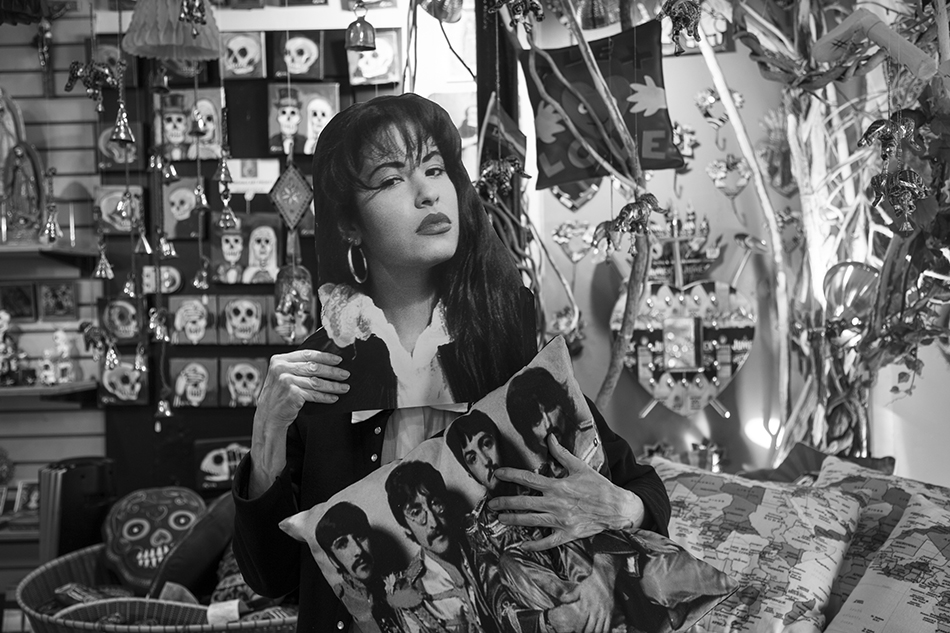

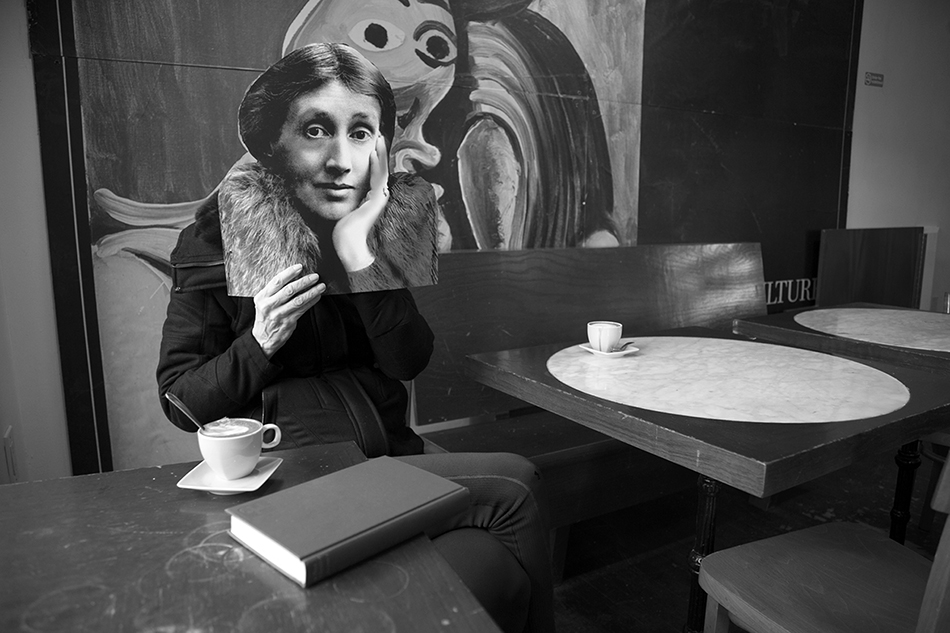

More recently, however, Henry, 72, has begun using her own persona in her work, creating staged photographs that show her posing in a mask — a tactic that allows her to investigate the many postures and facades of female identity. A selection of these works is now on view at BravinLee Programs, in Chelsea, through May 16. Titled “Hidden: Two Iterations,” the show is comprised primarily of works drawn from two series that Henry has made since 2014. In “Me as Her,” the artist poses behind masks she created from life-size, black-and-white portrait photographs of famous deceased women like Josephine Baker, Virginia Woolf and the Tejano pop star Selena. Shot on location in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where Henry lives and works, the resulting images look oddly believable — and contemporary, as if to suggest that the female archetypes these iconic figures represent are still very much alive today.

The show’s two series, both from 2014, explore the idea that historical archetypes of female identity are still very much alive.

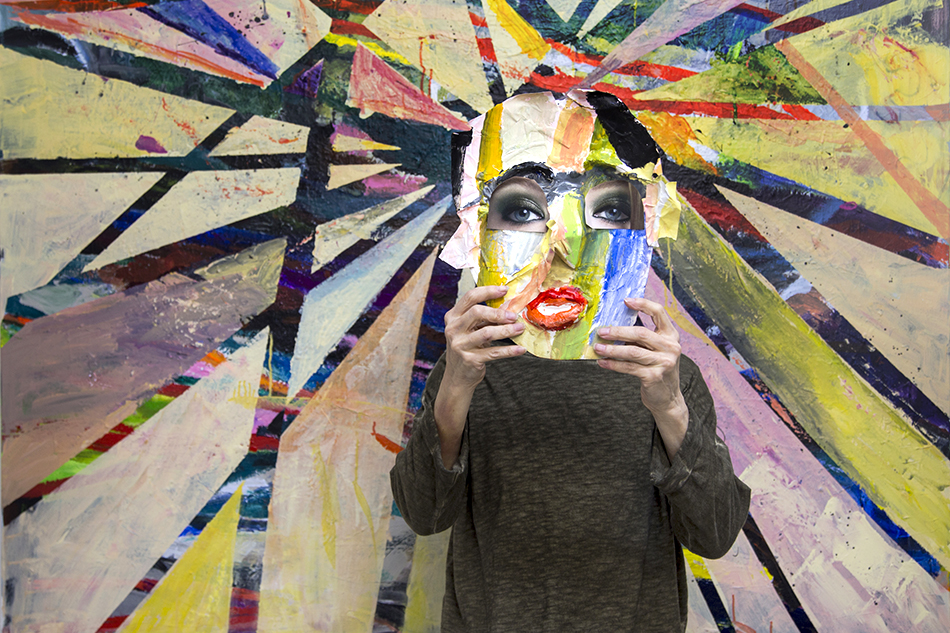

The works in the other series, “The Artist Is Hiding,” show Henry standing in her studio before a colorful abstract painting of her own making, wearing clothes that appear to meld with the composition. Although her face is always concealed — this time by masks she fashioned from a variety of materials, including collage, crinkled and marked-up paper and papier mâché — her slender hands are always clearly visible, underlining the notion that, in contrast to the title of the series, the artist is very much present.

The exhibition also includes an excerpt from “Girls Girls Girls,” a 2012–13 series for which Henry recreated pages from the yearbooks of all-girls schools, drawing each face, turning the drawing into a mask, re-staging each photograph with herself as the girl and reassembling the original page. Part drawing, part collage, part dress-up photography, part post-Minimalist grid, the results lie somewhere between collages by the Dada photomontagist Hannah Hoch and the early work of Cindy Sherman. “It really captures what it feels like to be behind the mask of a girl in high school,” says the dealer Karin Bravin, a partner in BravinLee.

Ironically, Bravin first discovered Henry’s work in another sort of yearbook — Facebook — when she spotted one of the “Artist Is Hiding” photographs posted by Henry’s longtime friend, Joyce Kozloff, an artist associated with the Pattern and Decoration movement that took shape in the United States in the 1970s. (Henry and Kozloff have known each other since they were students in the BFA program at Carnegie-Mellon University, in Pittsburgh, and they roomed together when they first moved to New York.) Bravin’s Facebook “like” resulted in an invitation to Henry’s studio, which so impressed the dealer that she found it hard to tear herself away. “Judy’s world is so huge,” Bravin says. “I watched videos; I let her read to me from her books. She really had me. I really wanted to take a chance on this person.”

Recently, Henry has begun using her own persona in her work, creating staged photographs that show her posing in a mask, a tactic that allows her to investigate the many postures and facades of female identity.

Exhibited at the Wooster Art Space in 2003, the mixed-media installation Walking and Talking featured a compendium of recording techniques Henry had used to document strangers on New York City streets over the course of many decades, incorporating layers of video footage, sound and photography.

That passion is echoed by Mary Birmingham, curator of the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, which will give Henry a solo show in 2016. “The work gave me chills. It just spoke to me on some level,” she says, adding that she, too, was introduced to Henry’s work by Kozloff. “I instantly thought, ‘I have to show this.’ ”

Henry wasn’t much older than the girls in her yearbook photographs when she arrived in New York in 1964. Transfixed by the city’s teeming masses — an exhilarating rush for someone raised in Cleveland, Ohio, where, she says, “we were always in a car and never saw people” — she began to photograph people on the street. A few years later, during her first week of work at Knopf, she overheard someone say in the elevator, “Her personality makes her prettier.” That chance comment led to a long-running engagement with work that matched photos with text, as in her “Triptychs” painting series (1979), which combined words and photo-transferred images, and the installation Walking and Talking, 2003, comprising prints, books and a video with a voice-over. It also resulted in text-and-photo installations in the windows of Bergdorf Goodman in New York and Neiman Marcus in Beverly Hills, as well as Henry’s “Overheard” book series, including Overheard at the Museum and Overheard While Shopping, published by Universe/Rizzoli between 2000 and 2001. (A later book, Overheard in America, was published by Atria Books in 2006.)

Henry’s marriage to the Argentinian conceptualist and video artist Jaime Davidovich resulted in Wooster Enterprises (1976–79). The short-lived collaborative aimed to inject conceptual art into the commercial world, by selling products by George Maciunas, a co-founder of Fluxus, and producing their own subversive cards and paper items, including the crumpled stationery and a notepad that said “things to do” on the front and “things not to do” on the back.

Henry’s work with masks began a few years ago, some time after she and Davidovich divorced: On a trip to Paris, Henry discovered in her rented apartment a high school yearbook from an all-girls school in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and was moved to sketch the youthful faces of the students. “They’re just starting out in life,” is how she explains her attraction to the images. “They’re just blank slates.” From there, Henry began wondering about the polar opposites of the girls — the very accomplished women who came to populate the “Me as Her” series.

The work came about “because of my own aging process,” Henry says. “I’m getting older and thinking about what I’ve done in my life.” And now, she adds, “after years of spying on other people and taking pictures and eavesdropping on what they said, I’ve begun to realize that I need to bring myself into the picture.”