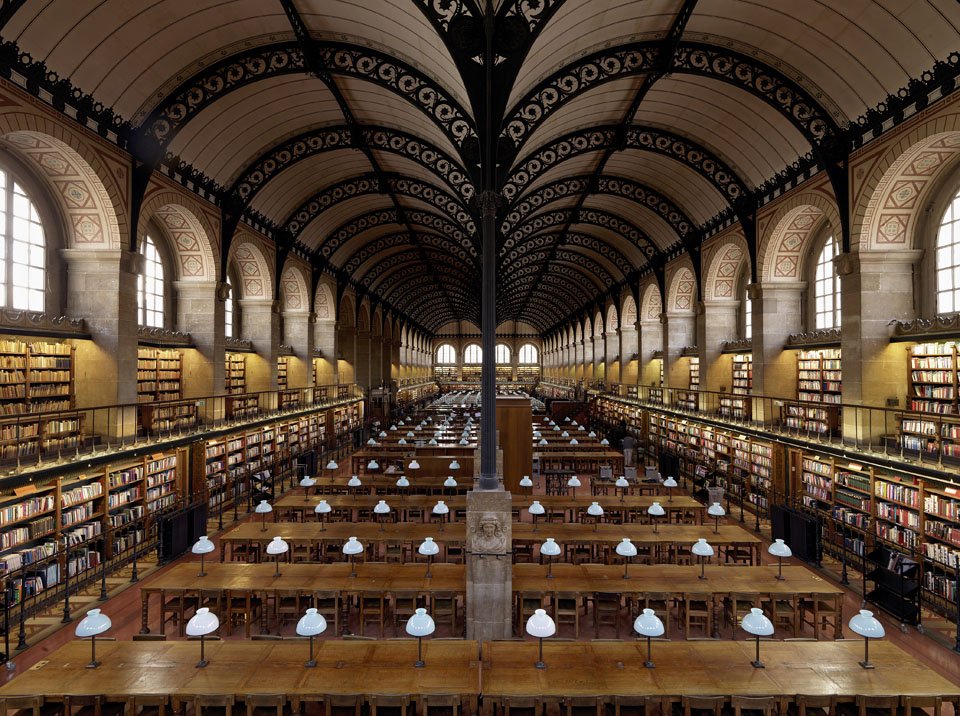

September 2, 2018Massimo Listri has translated his passion for ornate historic libraries into a book. Among those featured are two German monastery libraries: the Klosterbibliothek Wiblingen, in Ulm (above), and the Klosterbibliothek Metten, in Metten. All photos by Massimo Listri, courtesy of Taschen

It was inevitable that they would one day work together: Benedikt Taschen, the king of the coffee-table book, and Massimo Listri, the Florence-born photographer who specializes in capturing over-the-top interiors. (When he opened his doors to Introspective last year, Listri showed that he likes living in elegantly crowded rooms as much as he likes shooting them.) A photographer since his teens, Listri has published scores of books. But his first volume for Taschen, The World’s Most Beautiful Libraries, has just come out. It was worth waiting for. The book contains photos of libraries in Europe so ornate they make American attempts like the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue and the Huntington Library in Pasadena look under-ornamented. There are no contemporary examples — the National Library of Mexico, a glass-and-steel building that could nonetheless be termed baroque, didn’t make the cut, nor did the stunning libraries by Sir David Adjaye in Washington’s Anacostia neighborhood. The only U.S. structure is J.P. Morgan’s private library in Manhattan, which seems positively stripped-down compared to some of its European forebears.

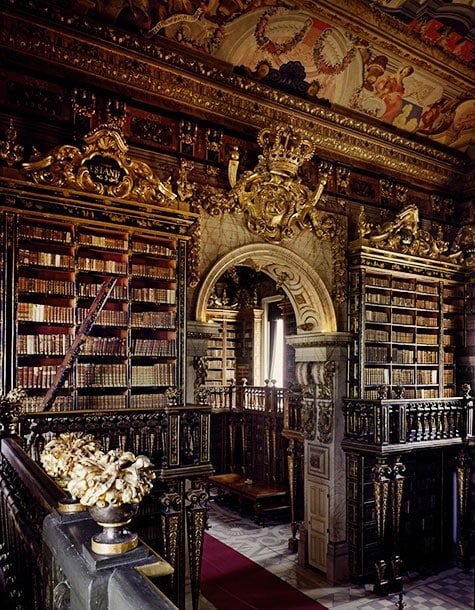

Biblioteca do Convento de Mafra, Mafra, Portugal

This book isn’t about libraries with magazine subscriptions and Wi-Fi passwords; it’s about the kind that lack heating systems because, as historian, librarian and author George Ruppelt points out in his masterly introductory essay, heating involved fire, and at the world’s great libraries fire was an ever-present threat.

Lest the whole thing be just too weighty, Ruppelt provides a leavening anecdote or two. He notes, for example, that until the 19th century, visitors to the Wolfenbüttel library (in Wolfenbüttel, Germany), where he once worked, “came first and foremost to see a printing error in a Low German Bible of 1731” — specifically, its version of the Sixth Commandment, which states, “Du solt ehe brechen,” meaning “Thou shalt commit adultery.”

Of the book’s 55 featured libraries, just five are in the New World. They include the Biblioteca del Convento de San Francisco de Asís, in Lima, Peru, built for Franciscan monks. “Faced with the challenge of conquering new territories,” the monks would have considered a monastery without a library the equivalent of a “fortress without an armoury,” writes Elisabeth Sladek, an expert in Baroque art and architecture who penned the descriptive text. “The library,” she adds, “was an expression of the complex association which at that time existed between religion and rule. Its holdings comprise not only standard works on Church history and theology, philosophy and the sciences, but also late medieval hymn-books, Bibles and dictionaries, including the first dictionary of the Spanish language compiled by the Royal Spanish Academy.”

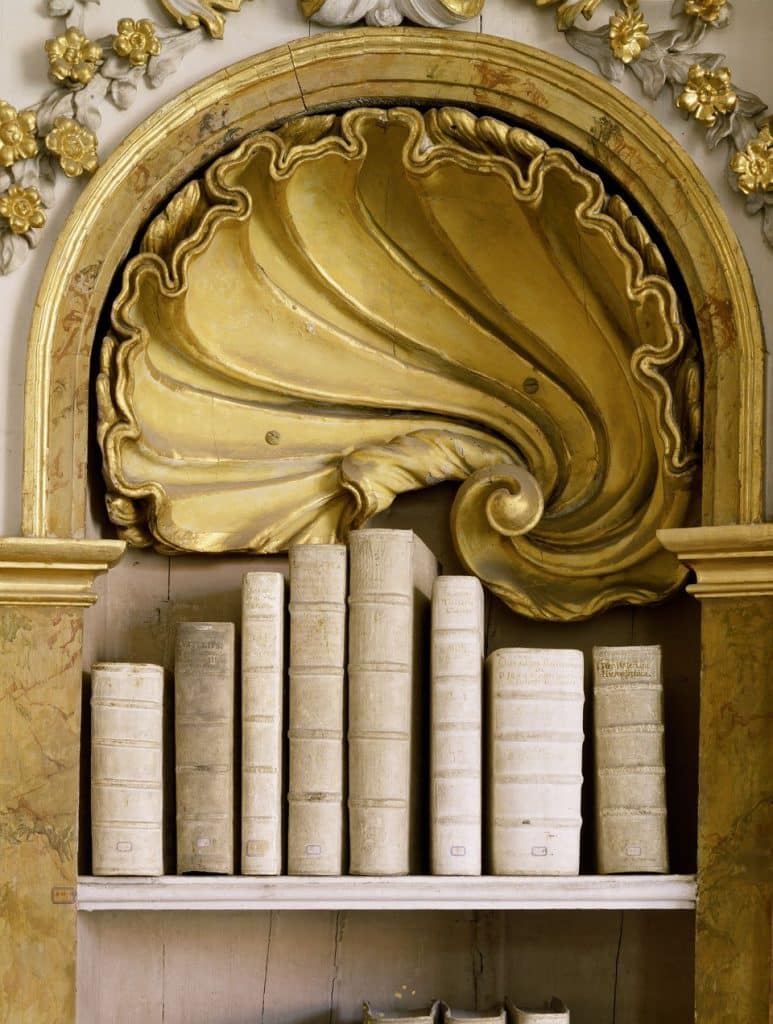

To her credit, Sladek makes an effort to delineate the contents of each featured library. And to Taschen’s credit, Listri’s architectural photos are accompanied by images of and from some of these works. This isn’t just about libraries as architectural wonders but about libraries as wonders of civilization.

Among the most astounding examples are those with lavishly painted walls and ceilings, such as the Rococo library of Wiblingen Abbey, completed in 1744; a riot of pinks and blues, with gold edges, it graces the book’s cover. But two of the most gorgeous libraries depicted are nearly monochromatic.

Real Gabinete Português de Leitura, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

One of them, the Biblioteca Statale Oratoriana dei Girolamini, in Naples, is a Late Baroque symphony of carved wood, with natural grain for decoration. Open to the public since its founding, in 1586, the library (which moved into its current home in the 1730s) holds “an exceptionally rich collection of manuscripts, incunabula, rare editions and old musical scores,” according to Sladek. (Her text, like Ruppelt’s, is provided in English, French and German.)

The Mafra Palace library, built by Portuguese kings at the royal hunting grounds near Lisbon and completed in 1771, is elaborate in form but muted in tone. Listri captures its glories in photographs, while Sladek recounts the less glorious history: The complex was paid for with the enormous quantities of gold arriving from the Portuguese colony of Brazil and was built by a conscripted workforce. It was allowed, under a 1745 Papal Bull, to house banned books.

Klosterbibliothek Wiblingen

Of the structures pictured in the book, the two oldest are the Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen, in Switzerland, and the Vatican Apostolic Library, in Rome, which date to the 8th and 9th centuries, respectively. Ruppelt’s text brings us into the present with his description of the UNESCO Memory of the World (MoW) program, established in 1992 to register “books, manuscripts and other documents preserved in libraries, archives and museums which represent the collective memory of humankind.” (As the UNESCO website explains, “Impetus came originally from a growing awareness of the parlous state of preservation of, and access to, documentary heritage in various parts of the world.”) The MoW Register comprises hundreds of items, ranging from the Bayeux Tapestry to a 1703 census of Iceland and including several in libraries shot by Listri.

Listri can’t photograph every library in the world, but his book — itself part of the memory of humankind — should be in every library’s collection.